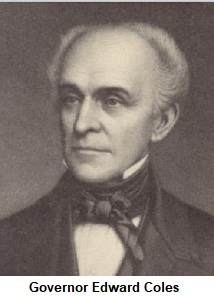

Governor Edward Coles (1786 - 1868)

"He Saved Illinois From the Curse of Slavery."

Edward Coles was born in 1786 in Albemarle County, Virginia. His

father was a Colonel in the army of the Revolution, and belonged to

one of the most distinguished families of the old Dominion. His

father was a friend and associate of Patrick Henry, Thomas

Jefferson, James Madison, Monroe, and other leading Virginia

statesmen, and it was in this atmosphere of greatness that young

Coles was brought up. Fitted for college by private tutors, he

completed his education at the college of William and Mary. After

leaving the institution, he spent two years in the study of history

and politics, and from his own reading and observation, became

imbued with views and principles

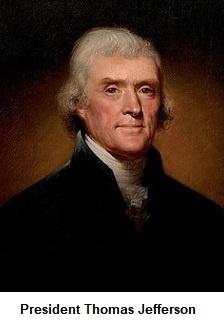

“The hour of emancipation is advancing with the march of time. It

will come, and whether brought about by the generous energy of our

own minds, or by the bloody process of San Domingo, is a leaf of our

history not yet turned over. As to the method by which this

difficult work is to be accomplished, if permitted to be done by

ourselves, I have seen no proposition so expedient on the whole as

that of the emancipation of those born after a given day, and of

their education and expatriation at a proper age.” Thomas Jefferson.

In 1815, Mr. Coles resigned his position as Secretary to the

President, and started on an exploring tour through the northwest,

in search of suitable lands on which to settle his slaves. He

traveled by buggy through Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, and

finally, on reaching St. Louis, sent his horses back home by his

servant, and descended the Mississippi to New Orleans, and thence

returned by sea to Virginia. About the time of his arrival, a

serious misunderstanding arose between the United States and Russia,

and it became necessary to send a special ambassador to St.

Petersburg to smooth over the difficulties, if possible. President

Madison selected Mr. Coles for this important and delicate duty.

Although the latter was engaged in making arrangements to remove to

Illinois, he consented at the President’s earnest request, to accept

the mission. The man-of-war “Prometheus” was detailed to take Mr.

Coles to Russia, and was the first American naval vessel that ever

sailed up the Baltic. Mr. Coles’ mission was completely successful,

and after its conclusion, he visited the various countries of

Europe, all American Ministers and Consuls being directed by

government to show him special attentions. At Paris, he was the

guest a great part of the time of 2General LaFayette.

After his return to America, he continued his preparations for

removal to Illinois, and in 1818 spent the summer at Kaskaskia, in

attendance on the convention engaged in forming a constitution for

the new State, using his influence to prevent any recognition of

slavery in that instrument. Returning home, he started for Illinois

with all his slaves in the Spring of 1819, intending to free them

before reaching his destination. The moral heroism displayed in this

step has few parallels. Here was a young man, rich, honored,

accomplished, deliberately sundering all social, domestic, and

political ties for the sake of principle; abandoning home, fortune,

luxury, refinement, and a brilliant career for the benefit of his

slaves. In New England, there were, doubtless, at that time some

abolitionists, but they had become such through education in a

different school, and sacrificed nothing in holding anti-slavery

sentiments. But here was a man, born in the atmosphere of slavery,

inheriting a well-stocked plantation, who had become a practical,

not a theoretical, abolitionist, through the force of his own

convictions, and in opposition to his surroundings and to the social

and political ideas of his kindred and friends. But over that home

of ease and luxury was the “trail of the serpent,” and he shrank

from the pollution. He bore with him to Illinois a flattering letter

of introduction from President Monroe to Illinois Governor Ninian

Edwards.

Mr. Coles’ slaves knew nothing of their master’s intentions.

Journeying through Pennsylvania in wagons, they finally embarked in

flatboats on the Ohio River, and one lovely April day, while

floating down the broad river, he called all the servants together,

made them an address, told them his intentions, and then announced

that they were free, “free as himself,” and at liberty to go ashore

or proceed with him as they pleased. The slaves were transfixed with

astonishment, unable to realize the import of his words, but at

length they burst into tears and hysterical laughter, and in

tremulous voices gave vent to their gratitude, and implored the

blessing of heaven on their benefactor. It was a strange scene,

worthy the brush of a painter. All refused to leave him, expressing

the desire to remain as his servants until he was comfortably fixed

in his new home. He then announced his intention of giving to each

head of a family 160 acres of land, and starting them comfortably in

the world. This they refused, but he kept his word, and on arriving

at Edwardsville, gave each one a deed to 160 acres of land in the

vicinity of his own farm. [Note: Robert Crawford, one of the former

slaves, was given property in Knox County (which used to be part of

Madison County), near Galesburg, Illinois.

Crawford later sold the property and moved to Madison County.] Coles also executed to each an instrument of

emancipation, which was duly recorded. He prefaced each instrument

by setting forth that his father had bequeathed to him certain negro

slaves, and added: “Not believing that man can have of right a

property in his fellow man, but on the contrary, that all mankind

were endowed by nature with equal rights, I do therefore by these

presents restore to (naming the party) that inalienable liberty of

which he has been deprived.” It may not be out of place to add here,

that all the slaves thus freed proved themselves industrious and

useful members of the community, led creditable lives, and showed

themselves worthy of the generosity of their noble benefactor.

Soon after his settlement in

Madison County, President Monroe appointed Mr. Coles Registrar of the Land Office at Edwardsville, in which

position he soon formed an extended acquaintance, charming all by

his genial manners and winning address, aided likewise by the

prestige of his previous career at Washington, and reputation as a

successful diplomatist.

In 1822 occurred the election for a successor to Governor Bond. The

most prominent candidate was Chief Justice Phillips. Mr. Coles was

brought out in opposition, and developed such strength in the

southeastern part of the State, that Judge Browne was put in the

field to aid Phillips by taking votes from Coles. Subsequently,

General Moore was also brought out. Phillips and Browne were

intensely pro-slavery. After an exciting contest, the election

resulted in 2,810 votes for Coles; 2,760 for Phillips; 2,543 for

Browne, and 522 for Moore; Coles receiving a plurality of 50 votes

over Phillips. The result showed that the candidacy of Browne

defeated Phillips. The aggregate vote was largely in favor of

slavery, Mr. Coles being elected by the division among the

pro-slavery men. The pro-slavery men elected their candidate for

Lieutenant Governor, Hubbard, by a large majority, and had nearly a

two-thirds majority in the legislature.

Governor Coles’ inaugural message was an admirable and far-seeing

document, filled with wise and statesmanlike recommendations. He

advocated the adoption of a sound financial policy; the development

of the agricultural resources of the State; the construction of a

canal connecting Lake Michigan and the Mississippi; the advancement

of education; and implored the Legislature to abrogate the remnant

of slavery that existed in the State, and also pass just and humane

laws in regard to the negroes. The anti-slavery recommendations had

the effect of the explosion of a bombshell on the pro-slaveryites. A

large majority of the inhabitants of the State were from the south,

and warm friends of slavery. They were thoroughly alarmed by the

message, and resolved to strike for a new constitution that should

permit slavery in the State. In explanation of the situation, Mr.

Washburne says:

“The first Illinois constitution prohibited slavery, and it may be asked how

it was possible that it could exist in Illinois at that time.

Illinois was a slave territory before it was ceded to the United

States by Virginia. The deed of cession provided that ‘the

inhabitants of the territory should have their possessions and

titles confirmed to them, and be protected in their rights and

liberties.’ This deed of cession was executed March 01, 1784. On July

13, 1787, Congress passed the ordinance providing that there should

be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the northwestern

territory. But the pro-slaveryites contended that this ordinance of

1787 was in conflict with the deed of cession, and therefore of no

binding effect.”

The early French inhabitants had held slaves, and still claimed that

right as did certain other settlers from the southern States, and

the census of 1820 showed that there were then 917 negroes held as

slaves in the State.

The Legislature at once appointed a committee on that portion of the

Governor’s message relating to slavery, which committee reported

that “the people of Illinois have now the same right to alter their

constitution as the people of Virginia, or any of the original

States, and may make any disposition of negro slaves they choose

without breach of faith or violation of ordinances, or act of

Congress,” and recommended the calling of a convention to alter the

constitution of the State.

The history of the struggle which then followed to fasten slavery on

the State is of intense interest, and we regret having to condense

it into a brief statement, leaving out details, and presenting only

the salient points. Under the existing constitution, no chance could

be made in that instrument, unless submitted to the people by a

two-thirds vote of the Legislature. The pro-slavery men had

two-thirds majority in the Senate, but lacked one vote of having

two-thirds in the House. And then commenced a campaign of

unparalleled rancor and bitterness. The anti-slavery minority,

animated by a love of freedom and supported vigorously by Governor

Coles, fought against the convention resolution with heroic

boldness and resolution. They stood a Spartan phalanx, unmoved by

threats and intimidation, resisting bribes and persuasion; rising

superior to public clamor, defying a multitudinous lobby influence

gathered at Vandalia from all parts of the State, and smiling

contemptuously at the curses and denunciations showered upon them.

The pro-slaveryites were at their wits’ ends. Failing to accomplish

their object by fair means, they resorted to foul ones. At the

opening of the session, before the convention resolution came up,

there had been a contested election case from Pike County - John Shaw and

Nicholas Hansen both claiming the seat from that county. The contest

was decided in favor of Hansen. The pro-slavery men, after weeks of

wrangling, thought they had obtained the requisite number of votes,

but when the matter came to a vote, Hansen, whom they had counted on

their side, voted against calling a convention. The pro-slavery men

were wild with chagrin and mortification. In their desperation, they

resorted to an outrageous act of injustice and stultification. They,

without any grounds whatever, reconsidered their vote on the

contested election case, unseated Hansen after he had been nine

weeks a member of that body, and seated Shaw. To accomplish their

ends, they violated every law of justice and rode rough shod over

all the rules of parliamentary procedure. Shaw was their pliant

tool. He voted for a convention, and by his aid, the requisite

two-thirds vote was obtained. But this act of Legislative injustice

returned to plague the inventors, and doubtless, in the subsequent

election, cost them the votes of hundreds of fair minded, although

pro-slavery men, who believed that the call for the convention was

illegally issued.

The convention men from all parts of the State were delirious with

joy over their triumph. They assembled in a grand procession,

paraded the streets of Vandalia, insulting Governor Coles and all

their principal opponents, and held a mad carnival of riot and

uproar. The object was to crush out at once all opposition. The

outlook was gloomy enough. There seemed no doubt but what the

resolution would be carried by the people, but the heroic Governor

Coles and the gallant anti-convention members resolved to fight the

issue out to the bitter end. As soon as the Legislature adjourned,

the Governor invited the anti-convention men to a consultation. They

determined upon immediate organization to fight against the

conspiracy to make Illinois a slave State. An address to the people

was prepared by Governor Coles, and signed by those members of the

Legislature who voted against the convention. This address, Mr.

Washburne says, “unmasked the purposes of the conspirators to make a

slave constitution, and exposed the disgraceful means used to

accomplish their purposes. It was an impassioned appeal to the

people to arise in their might and save the State from the impending

shame and disaster.” Speaking of slavery, Governor Coles' address said:

“What a strange spectacle would be presented to the civilized world

to see the people of Illinois, yet innocent of this great national

sin, and in the full enjoyment of all the blessings of free

government, sitting down in solemn convention to determine whether

they should introduce among them a portion of their fellow beings to

be cut off from these blessings, to be loaded with the chains of

bondage, and rendered unable to leave any other legacy to their

posterity than the inheritance of their own servitude. The wise and

the good of all nations would blush at our political depravity. Our

professions of Republicanism and equal freedom would incur the

derision of despots and the scorn and reproach of tyrants. We should

write the epitaph of free government upon its tombstone.”

“After dwelling,” Mr. Washburne says, “upon the moral aspects of

slavery, and arguing against its introduction as inexpedient for

material and economic reasons, the appeal closes with the following

stirring words by Governor Coles:”

“In the name of unborn millions who will rise up after us and call

us blessed or accursed according to our deeds, in the name of the

injured sons of Africa, whose claims to equal rights with their

fellow men will plead their own cause against their oppressors at

the tribunal of eternal justice, we conjure you, fellow citizens, to

ponder upon these things!”

This eloquent and thrilling appeal was signed by fifteen members of

the Legislature, dauntless, defiant, true-hearted men. They were:

3Risdon Moore, William Kinkade, George Cadwell, Andrew Bankson,

Jacob Ogle, Curtiss Blakeman (Madison County), Abraham Cairnes,

William Lowery, James Sims, Daniel Parker, 4George Churchill

(Madison County), Gilbert T. Pell, David McGahey, Stephen Stillman,

and Thomas Mather. Four other members of the Legislature voted against

the convention resolution, viz: Robert Frazier, Raphael Widen, J. H.

Pugh, and Nicholas Hansen (expelled to make place for Shaw). Their

names were not affixed to the appeal, probably because they had left

Vandalia before it was prepared. To sign this appeal required an

amount of moral courage and stamina, hard to appreciate at this day.

Issuing it in the face of a large pro-slavery majority in the State,

the signers not only risked their own political future, but exposed

themselves to social and business ostracism. As a sample of the

rampant pro-slavery spirit of the time, two of these signers, Risdon

Moore and George Churchill, were burned in effigy at Troy, Madison

County, for their anti-slavery sentiments. The signers to this

appeal, who fought the anti-slavery battle in this State, and did

more for Illinois and humanity than even themselves realized, are

worthy of the eternal gratitude of lovers of liberty everywhere.

The pro-slavery convention men also issued an address to the people,

prepared by a committee appointed at a public meeting of which

Colonel Thomas Cox of Sangamon was chairman. The signers were John

McLean, afterwards U. S. Senator; Judge T. W. Smith and Emanuel J.

West, both of Madison County; Thomas Reynolds, William Kinney,

Colonel A. P. Field, and Joseph A. Baird. The address endorsed the

action of the Legislature, and advocated the amendment of the

constitution. This document was a weak and tame manifesto compared

with the bold and eloquent appeal of the anti-slavery men. The issue

was now joined, February 1823, and both parties prepared for a

conflict which for the next 18 months, shook the State from center

to circumference, divided families, made enemies of friends, filled

the air with recrimination, and nearly resulted in civil war. Under

the constitution, the vote could not be taken on the convention

resolution until August 1824, when the next General Assembly was

elected, so that there was ample time for preparation. Both sides

were bitter, determined, and defiant. No quarter was given or asked.

Governor Ford in his history says:

“Newspapers, handbills, and pamphlets were thrown broad cast. These

missive weapons of a fiery contest were scattered everywhere, and

everywhere they scorched and scathed as they flew. The whole people,

for the space of months, did scarcely anything but read newspapers,

handbills, and pamphlets, quarrel, wrangle and argue with each other

whenever they met to hear the violent harangues of their orators.”

turned its

batteries against the convention. Next to Governor Coles, the man

who probably did the most effective work against the convention was

the 6Rev. John M. Peck, the great Baptist preacher [who founded the

Shurtleff College in Upper Alton], who labored assiduously in the

cause throughout the campaign. He organized the religious element on

the anti-slavery side, and under his inspiration, the pulpit

thundered anathemas against the convention. He organized societies

in fourteen counties under the control of a parent society at his

home in St. Clair. He traveled constantly, preaching a crusade

against slavery. Next to Mr. Peck, in good work accomplished, was

Morris Birbeck of Edwards County, a talented, highly educated

Englishman, a man of note and standing in his own country. He had

become acquainted with Governor Coles in England, and immigrating to

Illinois, he enlisted heart and soul with the Governor in the great

work. Upon the solicitation of Governor Coles, he employed his ready

pen continuously in the preparation of anti-slavery documents, and

in contributions to the newspapers. Of many others who took an

active part against the convention, especial mention should be made

of Judge Samuel D. Lockwood, David Blackwell, J. H. Pugh, George

Forquer, Daniel P. Cook, Thomas Mather, Henry Eddy, George

Churchill, 7Thomas Lippincott, Hooper Warren, and 8Curtiss Blakeman,

the last four of Madison County.

turned its

batteries against the convention. Next to Governor Coles, the man

who probably did the most effective work against the convention was

the 6Rev. John M. Peck, the great Baptist preacher [who founded the

Shurtleff College in Upper Alton], who labored assiduously in the

cause throughout the campaign. He organized the religious element on

the anti-slavery side, and under his inspiration, the pulpit

thundered anathemas against the convention. He organized societies

in fourteen counties under the control of a parent society at his

home in St. Clair. He traveled constantly, preaching a crusade

against slavery. Next to Mr. Peck, in good work accomplished, was

Morris Birbeck of Edwards County, a talented, highly educated

Englishman, a man of note and standing in his own country. He had

become acquainted with Governor Coles in England, and immigrating to

Illinois, he enlisted heart and soul with the Governor in the great

work. Upon the solicitation of Governor Coles, he employed his ready

pen continuously in the preparation of anti-slavery documents, and

in contributions to the newspapers. Of many others who took an

active part against the convention, especial mention should be made

of Judge Samuel D. Lockwood, David Blackwell, J. H. Pugh, George

Forquer, Daniel P. Cook, Thomas Mather, Henry Eddy, George

Churchill, 7Thomas Lippincott, Hooper Warren, and 8Curtiss Blakeman,

the last four of Madison County.

We will not dwell longer on the contest. The day of election came,

and the vote resulted:

Against the convention – 6,822

For the convention – 4, 950

Majority against – 1,872

Madison County voted:

Against the convention – 563

For the convention – 351

Majority against – 212

The attempt to amend the constitution was thus defeated, and

Illinois was saved from the leprosy of slavery. To Governor Coles

and his noble co-adjutors be all honor and praise. They “built

better than they knew,” and to them is due the fact that Illinois is

now the Empire State of the West, the peer of any State in the Union

in wealth, in prosperity and material development, and the home of

an educated, liberty-loving, happy people. And in the great national

struggle for liberty [Civil War], which opened 36 years later, under

another son of Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, there were no braver

soldiers than the sons of the anti-convention leaders, who rallied

under Governor Coles.

Throughout the remainder of his term, Governor Coles labored

zealously for the development and prosperity of the State, the

advancement of the cause of education, and the general welfare of

the people. In 1825, General LaFayette visited the United States,

and was received at Kaskaskia by Governor Coles, whose acquaintance

he had formed seven years before in Paris, and welcomed to Illinois.

The personal correspondence of these two great men, between whom

there existed a warm, personal friendship, is of great interest.

Governor Coles delivered his valedictory message to the Legislature

in

In 1832, Governor Coles removed permanently to Philadelphia, where

he was married in 1833 to Miss Sallie Logan Roberts. He never again

entered political life, but always took much interest in public

affairs. Mr. Washburne says: “Possessed of an ample fortune, his

private life seems to have brought him every charm and surrounded

him with every happiness. In person, he was about six feet in

height, and possessed a countenance of rare beauty. He lived

honored, respected, and beloved, to the good old age of 82, dying in

1868 after many years of feebleness. He was buried at Woodland near

Philadelphia.”

Governor Coles lived to see the nation redeemed from the curse from

which he saved the Prairie State. His widow, his oldest son, Edward

Coles Jr., and a daughter survive him and reside in Philadelphia. It is

an aphorism that “the world knows little of its greatest men.” Mr.

Washburne’s book, in enlightening the people of Illinois in regard

to the life and character of the man to whom they owe so much of

their present prosperity and happiness, will add new laurels to the

fame of its distinguished author.

Signed 9Wilbur T. Norton

**********

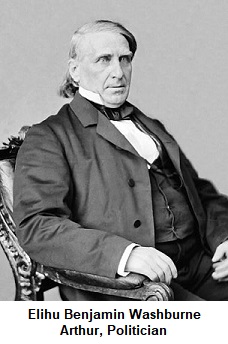

1Hon. Elihu B. Washburne (1816-1887) became a leader of the Radical

Republicans – those most ardently opposed to slavery, and was among

the original proponents of racial equality. After the Civil War,

Washburne advocated that large plantations be divided up to provide

compensatory property for freed slaves. He served as a member of the

House of Representatives from Illinois, was the 25th U. S. Secretary

of State, and was the U. S. Minister to France. In 1882, after he

retired, he published a biography [much of which the above

information was taken from] of former Illinois governor Edwards

Coles and the anti-slavery movement. Washburne moved to Chicago, and

served as president of the Chicago Historical Society from 1884 to

1887. In 1887, he published his memoir of his time as a diplomat.

His son, Hempstead, was elected Mayor of Chicago in 1891. Elihu

Washburne died at his son home in Chicago on October 22, 1887. He

was buried at Greenwood Cemetery in Galena.

2General LaFayette (1757-1834) was a French aristocrat and military

officer who fought in the American Revolutionary War, commanding

American troops in several battles, including the Siege of Yorktown.

After returning to France, he was a key figure in the French

Revolution of 1789, and the July Revolution of 1830. LaFayette was

commissioned an office at the age of 13. He became convinced that

the American revolutionary cause was noble, and traveled to the New

World seeking glory in it. He was made a Major General at age 19. He

was wounded during the Battle of Brandywine, but still managed to

organize an orderly retreat, and served with distinction in the

Battle of Rhode Island. In the middle of the war, he sailed home to

lobby for an increase in French support. He returned to America in

1780, and was given senior positions in the Continental Army. In

1781, troops under his command in Virginia blocked forces led by

Cornwallis, until other American and French forces could position

themselves for the decisive Siege of Yorktown. He returned to

France, and was elected a member of the Estates General of 1789.

3Risdon Moore (1760-1828) served in the Revolutionary War, as did

his brothers, Thomas and William. Risdon was the only one of three

brothers to survive the war. He served in Georgia Legislature in

1010, when he made a remark to an African-American during a class

meeting, “When dead, he would be free!” Because of this comment,

Risdon was indicted in Hancock County. Risdon sent his eldest son,

William, to Illinois to find “A more free and purer atmosphere.” He

and his family moved to Belleville, Illinois in 1812. He brought

with him sixteen slaves, in hopes of setting them free. As soon as

the slaves become of age, they were “allowed to look out for

themselves and use their own earnings.” Risdon served in the

Illinois government as the Speaker of the House of Representatives

in 1814, and was a member of the first, third, and fourth

legislatures. He was strongly opposed to making Illinois a slave

State.

4George Churchill (1789-1872) moved from St. Louis to Troy,

Illinois, in about 1817. He was a writer of great ability, and

amassed a large library concerning the early history of Madison

County. He became part owner, with Hooper Warren, of the

Edwardsville Spectator. In 1822, he was elected to represent Madison

County in the Illinois General Assembly. When the call came to hold

a convention for a new Illinois constitution, he put pen to paper

and wrote articles that “burned through the cuticle of ignorance and

sophistry.” He also served in the Illinois Senate.

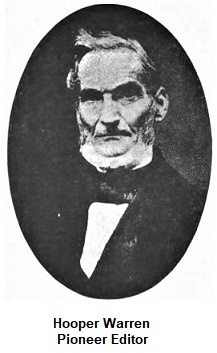

5Hooper Warren (1790-1864) learned the printer’s trade with Horace

Greeley. He entered the field of journalism in Frankfort, Kentucky,

and then in St. Louis, where he worked at the Missouri Gazette.

Under the tutelage of Governor Edwards, he established the

Edwardsville Spectator in 1819. This was the third Illinois

newspaper. George Churchill later joined Warren as co-owner. Warren

was the most unrelenting foe to slavery that ever lived in Illinois.

A distinction was drawn between Lovejoy’s observers by stating

Warren was anti-slavery, while Lovejoy was an abolitionist. In 1825,

Warren severed his connection with the Spectator, and moved to

Springfield. He founded the Sangamon Spectator in 1827. He was a

quiet man, and never gave public speeches. He was a good listener

with sound judgment, kind a tender-hearted. In 1812 he married Mary

Damson. He took ill in 1864 in Chicago, and died a few days later.

6Rev. John M. Peck (1789-1858) was an American Baptist missionary to

the western frontier of America. He, along with Rev. James Ely

Welch, established the First Baptist Church of St. Louis. In 1818,

he traveled to Kaskaskia, then the seat of government in Illinois.

In 1819, Peck set out to establish a seminary. At the end of April

1822, he and his family moved to St. Clair County, Illinois, and

founded Rock Spring Seminary, named after his farm. In 1832 he moved

the seminary to Upper Alton, and renamed it Shurtleff College after

a benefactor, Benjamin Shurtleff. Rev. Peck was considered an

innovator, with great zeal, power, and success. He was firmly

against slavery, and preached against it in his papers and sermons.

7Rev. Thomas Lippincott (1791-1869) moved to New York to St. Louis,

Missouri in 1819. He first worked as a clerk, and Colonel Rufus

Easton, founder of Alton, asked him to take goods and establish a

store in his newly founded town. Thomas loaded the goods onto a

boat, where he disembarked at Alton. He chose, however, to set up

the store in Milton, near the Wood River, which was more populated

at the time. After loosing two wives at Milton, from the malarial

fever, he moved to Edwardsville to get away from the unhealthy

climate. In 1822, he was elected as secretary of the Illinois State

Senate, and also became editor of the Edwardsville Spectator.

Through the newspaper and his public life, he took every opportunity

to aid in the struggle over slavery. Lippincott opposed calling for

a convention for a new Illinois constitution, and wrote some of the

most influential articles on the subject, which contributed to the

victory won by his party.

8Curtiss Blakeman (1777-1833) was a former sea captain from

Stratford, Connecticut, who settled in Marine, Madison County in

1819. He was elected to the third General Assembly of Illinois,

which convened at Vandalia on December 2, 1822. In 1824, he was

re-elected to the General Assembly. He was considered full of

practical wisdom, gained by life-long voyaging from land to land. He

was firm as a rock in the maintenance of right, and was firmly

against slavery.

9Wilbur T. Norton (1844-1925) was born in Alton and served in the

Civil War. He became editor and proprietor of the Alton Telegraph,

and later postmaster in Alton. As a newspaper man, he was devoted to

chronicling facts of historic nature, including writing the

Centennial History of Madison County, Illinois, and Its People.” He

died in 1925 in Alton, and was buried there.

Source: Alton Telegraph, December 8, 1881