County History

Explorations of Marquette and Joliet

During their four-month explorations to find a route to the

Pacific Ocean from New France (Canada), on June 17, 1673 Father

Jacques Marquette and fur trader Louis Joliet reached the

Mississippi River after traversing the Wisconsin River, and a few

days later their canoes were gliding past the shores of what would

be Madison County, Illinois. As they neared what would later be

Alton, they wrote in their journal:

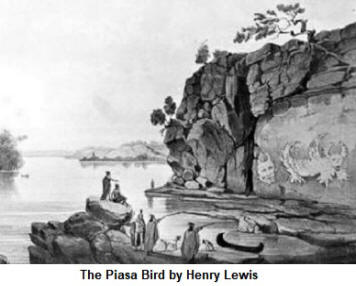

"As we coasted along rocks, frightful for their height and length,

we saw two monsters painted on one of the rocks, which startled us

at first, and upon which the boldest Indian dare not gaze long. They

are as large as a calf, with horns on the head like a deer, a

frightful look, red eyes, bearded like a tiger, the face somewhat

like a man's, the body covered with scales, and the tail

Such were the circumstances under which white men first saw this

part of Illinois. The rocks, which Marquette referred to, were the

bluffs which extend along the Mississippi northward from Alton. On

the face of the bluff, just above the present city of Alton, were

depicted the figures mentioned by Marquette, and with which we are

familiar of the famous legend of the Piasa Bird. Pioneers later

recalled that when every Indian, as he passed down the river in his

canoe, shot his arrow or his rifle at the monsters on the bluff.

The French, who made early settlements in the more southern

counties of Randolph, St. Clair, and Monroe, did not secure any

permanent hold within the limits of Madison County. On the east side

of the Mississippi, they founded no villages, probably from the fact

that by the treaty of Fountainbleau 1762, Illinois had passed to

English control. There is evidence that a Frenchman named Jean

Baptiste Cardinal made a settlement as early as 1785 at Piasa,

supposed to be the site of the present city of Alton. He built a

house and resided there with his family, but was taken prisoner by

Indians. His family fled to the village of Cahokia. Also, history

records that there was a French trading post at the future town of

Alton.

In 1800, there were a few French families residing on Big Island

(now called Chouteau Island after the Frenchman who planted an

orchard there), which was part of Madison County, across from

present-day Granite City. The residents planted an orchard in which

was a pear tree whose trunk, in 1820, grew to be a foot and a half

in diameter. On both Chouteau and Cabaret Islands (near Chouteau

Island) some French residents of Cahokia raised large numbers of

horses, which they shipped in flatboats to New Orleans. The

isolation of the islands provided escape-proof grazing lands and

safety from Indians. The orchard on Chouteau Island was claimed by

the flooding of the Mississippi long ago, as well as an old

graveyard, in which many of the early French residents were buried.

There were four kinds of land claims provided to early settlers:

1. Ancient grants were derived from former governments (French or

British) or from the Indians, under an act of Congress of June 20,

1788.

2. Donations to heads of families of 400 acres, for all those who

had become heads of families from the peace of 1783 to the passage

of the law in 1788.

3. Improvements Rights. Under the law of March 3, 1791, where lands

had been improved and cultivated, it was directed that claims should

be confirmed, not exceeding 400 acres to any one person.

4. Militia Rights. Under the act of March 3, 1791, a grand of land,

not exceeding 100 acres, was made to each person who had obtained no

other donation of land, and who on August 1, 1790, was enrolled in

the militia and had done militia duty.

Under the land claims the following received land in Madison County:

Nicholas Jarrot, heirs of James Biswell, William Bolin Whiteside,

heirs of Samuel Worley, James Kinkead, Isaac Darnielle, Isaac West,

Peter Casteline, Isaac Enochs, Abraham Rain, Larkin Rutherford,

David Waddle, John Edgar, Philip Gallaghen, James Haggin, Samuel

Judy, Ison Gillham, John Whiteside, John Rice Jones, Thomas Gillham,

John Biggs, John Blum, Uel Whiteside, Thomas Kirkpatrick, Henry

Cook, John Biggs, Benjamin Caster, Alexander Waddle, Ettienne

Pensonean, Hannah Hillman, Thomas H. Talbot, and James Whiteside.

The country comprising the present county of Madison was explored

by Reverend David Badgley, and others, in the year 1799. Reverend

David Badgley was a Baptist preacher who came to Illinois in 1796

and settled in St. Clair County, a few miles north of Belleville,

where he died in 1824. He was never a resident of Madison County.

The luxuriant growth of grass and vegetation and the fertile soil

reminded them of the richness of land in Egypt, in which the

children of Israel took possession of, “and where they grew and

multiplied exceedingly,” and they called the area Goshen.

The first American settler to push beyond the frontier and live in

Madison County was Ephraim Conner. This was in 1800, and he built

his rude cabin in the northwest corner of Collinsville Township. In

1801, he sold his land to Samuel Judy, who became a permanent and

valued citizen of the flourishing Goshen settlement. Samuel Judy was

the son of Jacob Judy, was born on August 19, 1773. He married

Margaret Whiteside, and in 1808 built a brick house, the walls of

which were cracked by the earthquake of 1811. This was the first

brick house erected in Madison County. In the early Indian troubles

in Monroe County, Samuel Judy, at the age of twenty, displayed great

courage in the campaigns against the Indians during the war of

1812-14. In 1812 he was in command of a company of spies, in advance

of the main army, which proceeded against the Indians at Peoria

lake, and in 1813, was Captain of a company in the army of General

Howard. In the frontier skirmishes with Indians, he was considered

active, efficient, prudent, and cautious. In 1812 he was elected

from Madison County as a member of the first legislature that

convened at Kaskaskia, after the forming of the Illinois Territory

government. After the organization of Madison County, he was one of

the first County Commissioners. He acquired wealth, raising large

numbers of horses, cattle, hogs and sheep. When the Alton

penitentiary was established in Alton, he was appointed as a member

of the board which had charge of the erection of the building and

placing the penitentiary system in operation. Samuel Judy died in

1838.

The first settlement on the Six Mile Prairie (so named because it

was six miles north of St. Louis) was made in the year 1801. A

family named Wiggins settled here, and with them lived an unmarried

man, Patrick Hanniberry.

The Gillhams

In the early history of Madison County, the most numerous family

were the Gillhams. Thomas Gillham, the first of the family to

immigrate to America, was a native of Ireland. He first settled in

Virginia in 1730, then moved to South Carolina. One of his sons,

James Gillham, was the first of the family to immigrate to Illinois

Country. James had married Ann Barnett in South Carolina and moved

to Kentucky. One day in June 1790, while plowing corn on his farm,

Kickapoo Indians entered his home and captured his wife and three

children, ranging in age from four to twelve years. The Indians

first ransacked their home, stealing clothing and other articles

they could carry on their backs. The group then traveled to their

village near the head waters of the Sangamon River in Illinois. They

pushed forward without rest or food, and the children’s feet became

sore and bruised. The mother tore her clothing to get rags in which

to wrap them. Together they endured great hardships as they

journeyed on foot to the Indian village on Salt Creek, about twenty

miles northeast of Springfield, Illinois. James arrived home after

plowing and saw the condition of his home and the footprints

outside. He knew what had happened. He followed the trail for a

time, but finally lost the trail and abandoned the pursuit. He sold

his land and went to Vincennes and Kaskaskia with the hope of

enlisting the aid of French traders, who had personal knowledge of

all the Indian tribes in the Northwest. After five years of

disappointment, he learned from the traders that his family were

among the Kickapoos, and with two Frenchmen as interpreters, he

visited the Indian town on Salt Creek, and found his wife and

children alive and well. A ransom was paid through an Irish trade at

Cahokia, by the name of Atchinson. The younger son, Clemons, could

not speak a word of English, and it was some time before he could be

persuaded to leave the Indian country. James Gillham had become

impressed with Illinois Country, and in 1797, two years after the

recovering of his family, he became a resident of Illinois. He first

settled in the American Bottom below St. Louis. In 1815, Congress

gave to Mrs. Gillham 160 acres of land at the head of Long Lake in

Chouteau Township, in testimony of the hardship and sufferings she

endured during her captivity among the Indians.

James Gillham, after settling in his new home, wrote to his brothers

in South Carolina of the advantages of the Illinois Country. His

brothers, Thomas, John, Isaac, and William came to Illinois and made

it their new home. Ezekiel Gillham, another brother of James, moved

to Georgia. One of his sons and two daughters came to Illinois in

1803. Sally Gillham, a sister of James, who had married John

Davidson who was killed in the Revolutionary War, had two of her

sons and one daughter come to Illinois and settled in Madison

County. Susannah, another sister of James, married James

Kirkpatrick, who was killed following the Revolutionary War. Four of

her sons came to Illinois and figured prominently in the early

settlement of Madison County. William Gillham settled in the Six

Mile Prairie as early as 1820 or 1822. He then moved to Jersey

County. John Gillham arrived in 1802 and settled in Edwardsville

Township on the west bank of Cahokia Creek. Isaac Gillham came to

Illinois in 1804 or 1805 and settled in the American Bottom.

The Gillhams were a moral family, and although born in a slave

state, they recognized the corrupting influence of slavery and

opposed its introduction into Illinois. At the convention party of

1824, the Gillhams and their relatives cast five hundred votes

against the proposition to make Illinois a slave state. It was

through the hard work and fortitude of this family that Madison

County owes its early history.

The Whitesides

Another prominent family in early Madison County history was the

Whiteside family. There were celebrated for their bravery and daring

in the troubles between settlers and the Indians. The head of the

family was William Whiteside, who was a soldier in the American

Revolutionary War. From the frontier of North Carolina, he

immigrated to Kentucky, and from there, he came to Illinois in 1793.

He settled first in Monroe county, and built a fort on the road

between Cahokia and Kaskaskia, which became known as Whiteside’s

Station. His brother, John Whiteside, came to Illinois about the

same time, and he had also been a Revolutionary War soldier. Colonel

William Whiteside was justice of the peace and judge of the court of

common pleas. In the war of 1812-14, he helped organize the militia.

He died at the old station in 1815. The Whitesides had been

neighbors of the Judy family, and coming to the Goshen settlement in

Madison County, they selected a location not far from Samuel Judy,

whose wife was a sister to Samuel Whiteside. Samuel and Joel

Whiteside, sons of John Whiteside, settled in the northeast part of

the present Collinsville Township, and made the first improvements

on the Ridge Prairie.

Samuel Whiteside was a representative from Madison County in the

first legislature which met after the admission of Illinois into the

Union as a State. He commanded a company of rangers in the campaigns

against the Indians during the War of 1812-14. In the Black Hawk

War, he was commissioned as a Brigadier-General.

William B. Whiteside filled the office of Sheriff of Madison County.

He was a son of Colonel William Whiteside. William B. served as a

Captain in one of the companies of U. S. rangers, organized in 1813.

On July 24, 1802, two men, Alexander Dennis and John Van Meter, were

murdered by Indians in the Goshen settlement, southwest of

Edwardsville, not far from where Cahokia Creek emerges from the

bluff, at the place afterward known as Nix’s ford. This murder was

committed by a band of Pottawatamies, led by their chief, Turkey

Foot, who was known as a cruel savage. Turkey Foot and his band were

returning from Cahokia to their town in the northern part of

Illinois. On meeting Dennis and Van Meter, they killed them without

provocation. The Indians were probably intoxicated, and this act did

not deter the growth of the Goshen settlement.

Other Early, Prominent Settlers

Other families that played a large part in the early settlement of

Madison County included the Grotts and Seybold families, who came in

1803. William Grotts and Robert Seybold had been soldiers in the

Revolutionary War. In 1785, Robert Seybold came down the Ohio River

in a flatboat, and walked from Fort Massac to Kaskaskia. Robert

married Mary Bull, a widow of Jacob Gratz who was killed by Indians

at Piggott’s Fort. Samuel Seybold, a former old resident of Ridge

Prairie, was born at Piggott’s Fort in 1795. Robert was one of the

pioneer settlers of the present Jarvis Township, making improvements

at the head of Cantine Creek, two and a half miles west of Troy, in

1803.

Dr. George Cadwell was an early settler on the banks of the

Mississippi, opposite Cabaret Island, not far above Venice. He and

John Messinger, made many early surveys in Madison County. They came

to Illinois in 1802, landing their boat in the American Bottom, not

far from Fort Chartres. Dr. Cadwell practiced the profession of

medicine, and was chosen to several public offices. He was justice

of the peace, and judge of the county court. Cadwell was the first

member of the State Senate from Madison County, and held that

position from 1818 to 1822. He was later a member of the legislature

from Greene County, and died at an old age in Morgan County.

John Messinger, who came with Cadwell to Illinois, lived a short

time within Madison County, then moved to St. Clair County. He first

lived in Ridge Prairie, between Troy and Collinsville. He assisted

in forming the first constitution of Illinois, and was Speaker of

the House of Representatives in the first General Assembly. He died

in 1846.

Rattan’s Prairie was named after Thomas Rattan who settled there in

1804. He came to Illinois from Ohio. Toliver Wright settled near the

mouth of Wood River in 1806. He was a Captain in the ranging service

during the War of 1812-14, and while in command of a company, he was

shot by an Indian. He was carried back to Wood River Fort, and died

in six weeks. Abel Moore made his home in the Wood River settlement

in 1808. He died in 1846 at the age of sixty-three. The death of his

wife occurred one day previous. Two of his children were killed in

the Wood River massacre. George and William Moore, brothers of Abel

Moore, left Kentucky at the same time, 1808, but went to the Boone’s

Lick country in Missouri, from which, in 1809, they came to Madison

County. The Reagan family, some of the members of which were victims

of the Wood River massacre, came to the Wood River settlement about

the same time as the Moores.

Thomas Kirkpatrick made pioneer improvements on the site of

Edwardsville. James Kirkpatrick, Frank Kirkpatrick, William Gillham,

Charles Gillham, Thomas Good, George Barnsback, George Kinder, John

Robinson, Frank Roach, James Holliday, Bryant Mooney, Josias Randle,

Thomas Randle, Jesse Bell, and Josias Wright made early settlements.

Southwest of Edwardsville, at the foot of the bluff, Ambrose and

David Nix were early settlers, and above them lived Jacob Varner.

Joseph Bartlett and the families of Lockhart and Taylor settled in

Pin Oak Township in 1809. During the war of 1812-14, Bartlett built

a block house. He was the first treasurer of Madison County. James

Kirkpatrick’s fort was a couple of miles southwest of Edwardsville,

and southeast was Frank Kirkpatrick’s fort. There was also the Beck

block house, and the Lofton’s and Hayes block houses. The Wood River

Fort was another fort about one mile south of the old town of

Milton. These forts and block houses were used as protection from

Indians.

In 1812, preparations were made by Ninian Edwards, the

Territorial Governor, for the protection of the frontier. Companies

of mounted rangers were organized, who scoured the Indian country.

Fort Russell was built in 1812, a couple of miles north of

Edwardsville, and it was made the headquarters of the Governor and

the base of his military operations. The Governor opened his court

at the fort, and presided with “genius and talent.” The cannon of

Louis XIV of France were taken from old fort Chartres, and with them

and other military decorations, Fort Russell blazed out with

considerable pioneer splendor. The fort was named in honor of

Colonel William Russell of Kentucky, who had command of the ten

companies of rangers to defend the western frontier. Four companies

were allotted to the defense of Illinois, and were commanded by

William B. Whiteside, James B. Moore, Jacob Short, and Samuel

Whiteside. A small company of regulars, under the command of Captain

Ramsey, were stationed at Fort Russell for a few months of 1812.

In 1812, preparations were made by Ninian Edwards, the

Territorial Governor, for the protection of the frontier. Companies

of mounted rangers were organized, who scoured the Indian country.

Fort Russell was built in 1812, a couple of miles north of

Edwardsville, and it was made the headquarters of the Governor and

the base of his military operations. The Governor opened his court

at the fort, and presided with “genius and talent.” The cannon of

Louis XIV of France were taken from old fort Chartres, and with them

and other military decorations, Fort Russell blazed out with

considerable pioneer splendor. The fort was named in honor of

Colonel William Russell of Kentucky, who had command of the ten

companies of rangers to defend the western frontier. Four companies

were allotted to the defense of Illinois, and were commanded by

William B. Whiteside, James B. Moore, Jacob Short, and Samuel

Whiteside. A small company of regulars, under the command of Captain

Ramsey, were stationed at Fort Russell for a few months of 1812.

After the War of 1812-14, settlements in Madison County rapidly

increased. A treaty of peace with the Indian tribes was concluded in

October 1815. In 1813, Major Isaac H. Ferguson built the first house

ever erected on the Marine prairie, but after building it, did not

dare to live there for some time because of Indian hostility. He was

a man of native talent, and as “brave as Julius Caesar.” He fought

the Indians in Illinois, and ended his life fighting as an officer

of the U. S. army in Mexico.

In territorial days, the early settlers were mostly of Southern

origin, and there were three classes of society: First, the white

man, born in a slave state, who thought of himself as a real

Westerner; Second was the African-American, generally a slave; and

Third, the Yankee from over the Mountains. After 1817, the county

received a large Eastern immigration, in which came individuals

whose merits raised them to positions of influence. This was

especially the case in the Marine settlement, at Edwardsville, and

later at Alton, whose rapid growth and business prosperity were

almost entirely due to Eastern men.

The early settlers were deeply religious, with Methodists and

Baptist the leading denominations. The settlers had a great

reverence for the law, were moral, and generally free from major

crime more so that later immigrants. Seldom was heard of any crime

greater than getting drunk or fighting. The first punishment of

crime recollected by Mr. S. P. Gillham was when an African-American

was found guilty of stealing coffee from a steamboat, and he was

whipped. Before jails were built, men were often punished by

whipping or confinement in the stocks.

Entertainment for early settlers included card playing, horseracing,

and shooting matches. The pioneers were friendly and sociable, and a

new-comer was given a hearty welcome. The women were brave and

self-reliant, and it was not unusual for the ladies to practice with

their rifle. They were often left alone, and at times they were the

only means of defense for their children.

The early settlers brought with them very little, besides their

axe and rifle. His first labor was to fell trees and build a cabin,

which was usually small and unpretentious. At one end of the home

was a huge fireplace, which was used for cooking and warmth.

Furniture was kept to a minimum with a table for eating, chairs, and

bedsteads. Each man was his own carpenter.

The clothing of the pioneer was simple. In the winter, moccasins

made of deer skin were worn, with the children going barefoot in the

summer months. The men wore shirts and vest, generally homemade of

flax and cotton. The trousers were of a coarse blue cloth, and often

buckskin. Homemade hats were worn made of fox, raccoon, and wildcat

skins. During the summer, hats were made of straw. For the ladies,

it was not unusual for her to appear dressed completely in clothes

made by her own hands. A bonnet of calico was worn outside. After

the loom and spinning wheel reached Illinois in 1818, dress styles

began to change.

The pioneers spent their day hunting and tending to animals and

crops. For the women, they tended to cooking and cleaning, making

and repairing clothing, and caring for the children. A passing

traveler once stated that the new country was heaven for men and

horses, but a hell for women and oxen.” Nevertheless, the women in

general were cheerful and happy.

Social gatherings were a favorite pastime, and women would enjoy

quilting and a spinning bee. With the men, they would test their

skills in shooting and hunting. After a day of socializing, they

would clear the floor and dance the night away with a local fiddler.

On the prairie, the settler was in constant fear of the dreaded

prairie fire in the autumn. It would begin in the high, dry grass,

and would sweep over the prairie faster than a horse could run. Each

settler usually burned off a strip of ground surrounding his farm,

and thus prevented the flames from destroying his crops and

buildings. If the prairie fire did start, the neighbors would be

engaged in fighting the flames well past midnight, in an effort to

save crops and homes.

The first camp meeting in Illinois was held near the residence of

Thomas Good, three miles south of Edwardsville, in the spring of

1807, with Rev. William McKendree, who was presiding elder of

circuits covering Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, and other western

states. Rev. McKendree became the fourth Bishop of the Methodist

Episcopal Church. Rev. Jesse Walker was his assistant preacher.

During this religious meeting, many people would curiously jerk – an

involuntary exercise which made the person sometimes dance and leap

until exhaustion made them fall to the ground. Another camp meeting

was held at Shiloh, six miles northeast of Belleville. The old

Bethel Church in Madison County, and the Shiloh Church in St. Clair

County, were the two earliest Methodist Churches in Illinois.

Prior to 1807, pioneers held regular religious services about once a

month. These two-days meetings were well attended. Josias Randle was

among the best-known Methodist preachers in early days.

A Baptist Church was constructed in Wood River Township in 1809. The

building was a small cabin, constructed of logs, and Rev. William

Jones was the first preacher who held services there. Other early

Methodist ministers included Peter Cartwright (the “fighting

preacher), Thomas Oglesby, Benjamin Young, Thomas Randle, Nathaniel

Pinckard, Samuel Thompson, and John Dew.

In 1812, a school was taught in the yard of the residence of Colonel

Samuel Judy, by Elisha Alexander. A schoolhouse was constructe4d in

1914 at the foot of the bluff, halfway between Colonel Judy’s and

William B. Whiteside’s homes, but more than half of the time it was

not occupied. This schoolhouse was a cabin of logs, and Mr. Thompson

was the first teacher. This was during the War of 1812-14, and many

of the inhabitants were engaged in ranging service. Another school

was taught by Vaitch Clark in the summer of 1813, in a block house

at the little fort which was located in Chouteau Township. The first

teacher in the Wood River settlement was Peter Fliun, in Wood River

Township. In Nameoki Township, the first school was taught in 1812

by Joshua Atwater, who was succeeded by an Irishman named

McLaughlin. The first school taught in the Marine Prairie was in

1814, in the smokehouse of Isaac Ferguson. There were ten or twelve

scholars, with Arthur Travis as the teacher. Hiram Rountree was an

early teacher at Ebenezer, southwest of Edwardsville; Mr. Campbell

at Salem; Joseph Berry on Sugar Creek; and William Gilliland at the

Cantine School. One of the early schools in the southern part of

Madison County was taught in Chilton’s Fort by David Smeltzer.

The Rev. William Jones was one of the earliest teachers in Fort

Russell Township. In 1817 Mr. Wyatt taught in this part of the

county, and in 1818 Daniel A. Lanterman taught school there.

Lanterman taught thirty-three children, and was paid twelve dollars

a year for each pupil. In the neighborhood of Edwardsville, there

were no good schools until 1818. About that time, Hiram Rountree

taught two years at the old Ebenezer schoolhouse. The first school

in the neighborhood of the present town of Troy was taught by

Greenberry Randle, in the year 1811.

The New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811-1812

On December 16, 1811 a large earthquake, estimated to be of 7.5 –

7.9 magnitude, with the center being near the town of New Madrid,

Missouri, occurred. In the American Bottoms, chimneys were thrown

down, and the walls of the brick homes were cracked. Animals were

frightened, with cattle running home to their barns. The shaking

caused the church bell in Cahokia to sound. Governor Reynolds stated

that his parents and children were all sleeping in a log cabin at

the foot of the bluff, when the shock came. His father leaped from

bed, crying “The Indians are on the house!” No one in the family

realized at that time it was an earthquake. An aftershock occurred

on the same day, estimated to be 7.4 magnitude. Because of sparse

population, no lives were lost and no serious damage occurred.

The second earthquake occurred on January 23, 1812. This was judged

to be the least severe, and had little observers since the Ohio

River was iced over, and there was little river traffic and fewer

human observers.

The third earthquake occurred February 7, 1812 and was estimated to

be 7.5 magnitude. The town of New Madrid was destroyed.

These three major earthquakes caused the ground to rise and fall,

opening deep cracks in the ground. Deep seated landslides occurred

along steep bluffs and hillsides, and large areas of land were

uplifted permanently, while other areas sank and were covered with

water. Huge waves on the Mississippi River overwhelmed many boats

and washed others high onto the shore. Banks caved in and collapsed

into the river, and whole islands disappeared. The damage covered an

area of 78,000 - 129,000 square kilometers, extending from Cairo,

Illinois to Memphis, Tennessee. Large waves were generated on the

Mississippi River, and local uplifts of the ground and water waves

moving upstream gave the illusion that the river was flowing

upstream.

Some pioneers stated that an earthquake was felt in Kaskaskia in

1804 and small quakes continued for years in Illinois. Many people

became alarmed, and those who had never thought before of being

religious, joined the church and began to pray, thinking the end was

at hand.

The Formation of Madison County

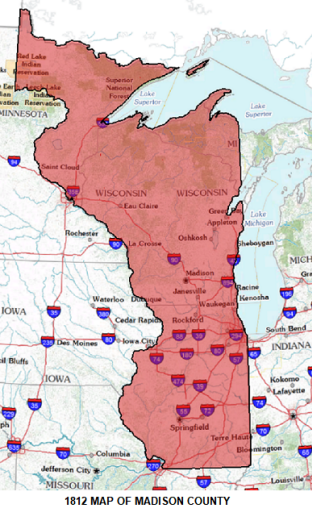

On September 14, 1812, Madison County was established in the

Illinois Territory out of Randolph and St. Clair Counties, by proclamation of

the Governor of Illinois Territory, Ninian Edwards. It was named for

U. S. President James Madison, a friend of Edwards, and had a

population of 9,099 people. At the time of its formation, Madison

County included all of the modern State of Illinois north of St.

Louis, as well as all of Wisconsin, part of Minnesota, and

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Territory out of Randolph and St. Clair Counties, by proclamation of

the Governor of Illinois Territory, Ninian Edwards. It was named for

U. S. President James Madison, a friend of Edwards, and had a

population of 9,099 people. At the time of its formation, Madison

County included all of the modern State of Illinois north of St.

Louis, as well as all of Wisconsin, part of Minnesota, and

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

A meeting was held on April 5, 1813 at the home of Thomas

Kirkpatrick in Edwardsville, where appointed commissioners were to

report on their selection of a county seat. A meeting was held on

January 14, 1814, where the court ordered the sheriff to notify the

commissioners appointed by law to fix the place for the public

buildings (courthouse and jail) for Madison County. The county seat

was established in the town of Edwardsville, with the first public

building – the jail – being erected in 1814. The first county

courthouse was erected in Edwardsville in 1817.

During the period 1819 to 1849, Madison County was reduced in area

to its present size, about 760 square miles. All of the public lands

had become the property of individuals and had been converted into

thousands of productive farms. New towns and villages were

established, such as Collinsville, Highland, Marine, Venice,

Monticello [Godfrey], Troy, and Alton.

Madison County Court Established

The year 1849 found the county subdivided into sixteen precincts:

Highland, Saline, Looking Glass, Marine, Silver Creek, Omphghent,

White Rock, Collinsville, Edwardsville, Troy, Bethel, Upper Alton,

Six Mile, Madison, Alton, and Monticello. A county court was

established, with Henry K. Eaton as judge, and I. B. Randle and

Samuel Squire associates. One of the first measures of this court

was to bring order into the financial chaos. This court, in 1849,

aided the construction of a plank road from Edwardsville to Venice,

by granting to the plank road company the right of way. In case that

new bridges were necessary, the company was to pay each one half of

the costs.

At the March term in 1850, large claims for taking care of paupers

were presented, but were not allowed, due to the fact that the

county finances were not in good condition. The court did, however,

establish a poor house to care for those in need. Also, during the

1850 term in court, the Collinsville plank road company obtained the

same privileges granted to the Edwardsville company.

At the June 1850 term, W. W. Jones, who had contracted with the

county for keeping the poor house, was released, and a new contract

entered into with Robert Stewart, who was to have $624 per annum for

keeping, feeding, clothing and nursing the inmates, provided their

average number was not more than six. At the July 1850 term, a

preamble and resolutions were adopted for Madison County.