African-American History in Illinois and Madison County

French Colonization of the Americas

The French colonization of the Americas began in the 16th century.

(Click here for a map of French America in 1688.) They

established colonies on a number of Caribbean islands and in South

America. As they colonized the New World, they established forts and

settlements which became cities such as Quebec and Montreal in

Canada; Detroit, Green Bay, St. Louis, Cape Girardeau, Mobile,

Biloxi, Baton Route, and New Orleans in the United States. France

came to the New World to seek a new route to the Pacific Ocean, and

to export products such as fish, rice, sugar, and furs.

The French were the first to explore the Illinois Country in 1673,

when Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet descended the Mississippi.

The French controlled the new territory, then known as “Illinois

Country,” first as part of French Canada, and then as part of

Louisiana. In 1699, priests of the Quebec Seminary of Foreign

Missions founded the Holy Family Mission at Cahokia – the first

permanent settlement in Illinois Country.

Introduction of Slavery in Illinois

Country

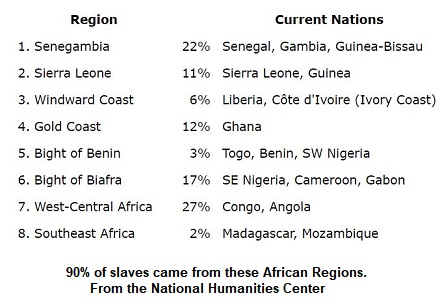

On September 14, 1712, Sieur Antoine Crozat was given control of the

French colony of La Louisiane (Louisiana) by the French government,

and was authorized at the same time to open a traffic in slaves with

the coast of

By the middle of the eighteenth century, the French had established

five settlements, including Kaskaskia, Kohokia (Cahokia), Fort

Chartres, St. Philip, and Prairie du Rocher. M. Vivier, the French

missionary to the Illinois Native Americans, described the region in

June 1750:

“We have here whites, negroes, and Indians, to say nothing of

cross-breeds. There are five French villages and three villages of

the natives within a space of twenty-one leagues. In the five French

villages, there are perhaps eleven hundred whites, three hundred

blacks, and some sixty red slaves, or savages. The three Illinois

towns do not contain more than eight hundred souls [natives] all

told.”

After the French and Indian War

(1754-1763)

After the French and Indian War (1754-1763), Great Britain gained

control

“M. Beauvais, owned 240 arpens [French measurement of land,

equal to about 0.85 acres] of cultivated land and eight slaves; a

captain of militia at St. Philip owned twenty slaves; and M. Balet,

the richest man in Illinois, who resided at St. Genevieve, owned a

hundred slaves, besides hired white people.”

The populations had decreased at the time to about sixteen hundred

inhabitants, of whom six hundred were slaves. By the end of the

century, migration from the East and South had begun, which

considerably increasing the population. The English government laid

no restrictions upon the holding of negroes as slaves by settlers of

this region.

After the American Revolutionary War

From 1775 – 1783, the American Revolution was fought and won. George

Rogers Clark [American

When Virginia ceded her claim on the Northwest Territory, she

stipulated that the French, Canadian, and other inhabitants of

Kaskaskia and neighboring villages should be allowed to retain their

possessions and to enjoy their ancient rights and liberties. These

privileges were granted by Congress in 1787, but a clause

prohibiting slavery in the district “Northwest of the Ohio River”

was inserted in the same document. The residents of Illinois Country

were considerably disturbed by the slave clause. Governor Arthur St.

Clair [of the Northwest Territory] chose to interpret the clause as

intended only to prevent the introduction of slaves, and not as

aiming at the emancipation of those already there. The view of the

governor was universally accepted, and slavery continued.

The Slave Codes

By 1803, it was necessary to provide some legal status for the

numerous indentured blacks, and to regulate relations between

masters and servants. The Governing Council of Indiana proceeded to

draw up a slave code, with the chief material obtained from the

codes of Virginia and Kentucky. These laws were re-enacted by the

Indiana Territorial Assemblies of 1805 and 1807. Under this code:

- All male negroes under the age of fifteen, either owned or acquired, must serve until the age of thirty-five.

- Women served until the age of thirty-two.

- Children born to the slaves during their period of service could also be bound out – the boys for thirty years, and the girls for twenty-eight.

- Slaves brought into the Territory were obliged to serve the full term of their contracts.

- Owners were required to register their servants with the County Clerk within thirty days after entering the Territory. Transfers from one master to another were permitted, provided the slave gave his or her consent. Other provisions included the duties of masters to servants.

- Wholesome food and sufficient clothing and lodging were to be provided each slave. The outfit for a servant was to be: “A coat, waistcoat, a pair of breeches, one pair of shoes, two pair of stockings, a hat, and a blanket.” No provision was made for a future increase of wardrobe, and there was no penalty connected with a failure to provide as instructed.

- On order from the Justice of the County, a servant was whipped for indifference or laziness, however, landowners were left unmolested in the management of their estates, and the question of the treatment of servants was seldom, if ever, raised. Those servants who refused to work or tried to runaway were forced to serve two days extra time for every idle or absent day.

- Anyone harboring a runaway slaves had to pay the master one dollar for each day that he concealed the slave.

- It was forbidden under severe penalty to trade or deal with a servant without the consent of his master.

- Slaves were not allowed to serve in the State militia, to have bail when arrested, to engage in unlawful assembly, or to absent themselves from the plantation of their owner without a special pass or token.

- If any slave refused to serve his master when brought into Illinois, the owner could move to any of the slave States with his property within sixty days. In the counties of Gallatin, St. Clair, Madison, and Randolph, there were over three hundred slaves registered in the decade following 1807. The number increased in the Territory from one hundred and thirty-five in 1800, to seven hundred and forty-nine in 1820.

These Slave Codes effectively barred slaves from gaining their freedom by permitting lengthy terms of “indentured servitude,” which bound workers to a particular person for a period of time in return for food and shelter.

Illinois Territory Created, March 1,

1809

Illinois Territorial Governor Ninian Edwards maintained in 1817 that

the Ordinance of 1787 permitted “voluntary” servitude, meaning the

indenturing

of

Africans for limited periods of service. He advocated reducing the

term to one year. He advanced the belief that such contracts were

“reasonable within themselves, beneficial to the slaves, and not

repugnant to the public interests.” Some citizens believed that

since the French had the right to retain their slaves, the other

settlers of Illinois had the same right. Governor Ninian Edwards

owned slaves: Rose, twenty-three years of age, was registered for

thirty-five years; Antony, forty years old, for fifteen years;

Maria, fifteen years of age, for forty-five years; and Jesse,

twenty-five years of age, for thirty-five years of service. Joseph

was registered at Kaskaskia on June 14, 1810, when he was eighteen

months old, and had just been brought into the Territory with his

mother.

of

Africans for limited periods of service. He advocated reducing the

term to one year. He advanced the belief that such contracts were

“reasonable within themselves, beneficial to the slaves, and not

repugnant to the public interests.” Some citizens believed that

since the French had the right to retain their slaves, the other

settlers of Illinois had the same right. Governor Ninian Edwards

owned slaves: Rose, twenty-three years of age, was registered for

thirty-five years; Antony, forty years old, for fifteen years;

Maria, fifteen years of age, for forty-five years; and Jesse,

twenty-five years of age, for thirty-five years of service. Joseph

was registered at Kaskaskia on June 14, 1810, when he was eighteen

months old, and had just been brought into the Territory with his

mother.

Slave Trafficking

No attempt was made to conceal the traffic in slaves. The St. Louis

Exchange and Land Office, owned by S. R. Wiggins, dealt largely in

slaves, and not only advertised in the Illinois papers, but also had

branch offices at Kaskaskia and Edwardsville. It was easy for the

settlers of Southwestern Illinois to cross the Mississippi River to

St. Charles or St. Louis to purchase slaves. In the first

publication of the “Western Intelligencer,” rewards were offered for

runaway slaves, and the practice of kidnapping had begun. Slaves

whose terms of service were about to expire were seized and carried

off to New Orleans or elsewhere in the South, and sold into a

servitude more wretched than before. Slavery continued in existence

in Southern Illinois as far north as Sangamon County.

Illinois Statehood, December 03, 1818

On December 03, 1818, the State of Illinois was admitted to the

Union, with Kaskaskia being the capital, and Shadrach Bond the first

Governor of Illinois. Some in the new State of Illinois would have

liked to have had Illinois as a slave State, however, many citizens

found it abhorrent to their Christian faith. A Constitutional

Convention was to meet at Kaskaskia in August 1818. As early as

April 1, articles discussing the advisability of making Illinois a

slave State, and vice versa, began to appear in the “Western

Intelligencer.” There were twenty-one delegates against the

introduction of slavery, and twelve in favor of it.

ILLINOIS HISTORY

Source: Alton Telegraph, May 23, 1889

When Illinois was first admitted to Statehood in 1818, the question

of slavery was foremost in the laying of the foundation of our State

government. It was a long and bitter struggle by our forefathers, as

to whether or not Illinois would be a slave State. The question was

debated for eighteen months on the “stump,” at the crossroads, from

the pulpit, in the newspapers (which were few and far between), and

at the family fireside. Finally, a vote of the people was held on

the first Monday in August 1824. The results of the vote is listed

below by counties, as they existed at the time.

Alexander – 75 for; 51 against

Bond – 53 for; 240 against

Clark – 32 for; 113 against

Crawford – 134 for, 262 against

Edgar – 3 for; 234 against

Fayette – 125 for; 121 against

Franklin – 170 for; 113 against

Fulton – 5 for; 60 against

Gallatin – 596 for; 133 against

Greene – 134 for; 405 against

Hamilton – 173 for; 85 against

Jackson – 180 for; 93 against

Jefferson – 99 for; 43 against

Johnson – 74 for; 74 against

Lawrence – 158 for; 261 against

Madison – 351 for; 583 against

Montgomery – 74 for; 90 against

Monroe – 171 for; 196 against

Morgan – 43 for; 455 against

Pike – 23 for; 261 against

Pope – 278 for; 124 against

Randolph – 357 for; 184 against

Sangamon – 155 for; 722 against

St. Clair – 427 for; 543 against

Union – 213 for; 240 against

Washington – 112 for; 173 against

Wayne – 189 for; 111 against

White – 355 for; 326 against

The “Black Laws”

While slavery in the newly formed State of Illinois was outlawed by

the State constitution, a compromise was made. In 1819, the State

legislature passed what was known as the “Black Laws.”

- Limited slavery would be allowed in the salt mines near Shawneetown. These contracts were limited to one year, but were renewable.

- All contracts and indentures made before 1818 were to be enforced, and all slaves had to serve out the full term of years for which they had been bound under the Territorial laws. However, children of indentured servants were to be freed – males at twenty-one years of age, and females at eighteen years of age.

- Current slave owners could retain their slaves.

- If a black resident was unable to present proof of their freedom, they could be fined $50, or sold by the sheriff to the highest bidder.

- The slave owners had to right of sale or transfer of a contract or indenture from one master to another.

- Black people were forbidden to settle or reside in the State without a certificate of freedom.

- It was unlawful to bring slaves into the State for the purpose of emancipating them.

1824 Contest for an Illinois

Constitutional Convention

The question of the admission of Missouri into the Union was debated

in Congress during the winter of 1818 to 1819. Many citizens in

Illinois were outspoken in opposition to the formation of another

slave State on their border. Missourians resented the efforts of

some in Illinois to stop their admittance in the Union, which set in

motion a scheme for the contest for a Convention in Illinois to

re-introduce slavery into Illinois. It was decided to establish a

pro-slavery newspaper at Edwardsville, to set the movement into

operation. This movement failed, however, when Mr. Hooper Warren,

editor of the Edwardsville Spectator and a staunch opponent of

slavery, became aware of their plans. He exposed the whole plot in

an editorial on July 11, 1820, emphasizing the fact that a

determined effort to force a slave constitution upon the people of

Illinois would be made within the next two or three years.

The result of the anti-conventionalists in Illinois was regarded as

an anti-slavery victory. The population in the State increased

rapidly through immigration. However, the courts sustained masters

in their right to hold slaves, and the Legislature showed little

interest to repeal the “Black Laws” of 1819. In 1827 and 1829, laws

were passed forbidding black people to act as witnesses in the

courts against any white person, and prohibited them from suing for

their freedom.

The Slave Hunters

Even though laws were enacted against kidnapping a slave when his

time of servitude was almost up, and sell him in the South, a system

was set up by two or three men, where one would establish himself as

a seller of slaves in St. Louis or at a border town. The other men

would move about the Illinois counties on the lookout for either

free or enslaved black people. When they could get away with it, the

“slave hunters” seized their victims or enticed them to accompany

them under false promises, placed them in wagons, and drove as

quickly as possible to the borders of the State. They usually got

away, but occasionally were overtaken and compelled to release their

captives. Another method of capture was to take the black man to a

spot on the Mississippi or Ohio River, where they were smuggled on

board ships and forwarded to Memphis or New Orleans, where they were

sold into slavery.

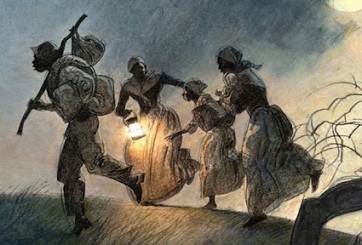

The Birth of the Underground Railroad

Those citizens in the State who were anti-slavery were happy to see

a poor slave escape safely from bondage, and were quite willing to

assist him when necessary. Out of this struggle between the slave

hunters and the anti-slavery citizens grew the Underground Railroad,

which aided those trying to escape to the North in safety. So bitter

was the animosity felt by the pro-

The Effect of the Murder of Rev. Elijah

P. Lovejoy

Following the death of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy in November 1837 at the hands of a pro-slavery mob, the hearts and efforts

of anti-slavery men were either frightened or forced into silence.

For a time, they proceeded with great caution. Following his death,

Lovejoy’s newspaper, The Observer, continued for a short time in

Cincinnati, Ohio, with Elisha W. Chester as editor. A lack of funds

caused its suspension in April 1838. However, a leading feature of

the anti-slavery movement in Illinois was the prominence of

clergymen who took up the mantle. Foremost among them were Owen

Lovejoy (Rev. Elijah Lovejoy’s brother), John Cross, W. T. Allen,

Chauncey Cook, James H. Dickey, Rev. Thaddeus B. Hurlbut, and Rev.

Hubbell Loomis.

The Anti-Slavery Convention in Upper

Alton, Illinois – 1837

In the Fall of 1837, a convention “favorable to immediate

emancipation of slaves” was called to meet at the Presbyterian

Church in Upper Alton, at the northwest corner of College Avenue and

Clawson Street. There were nearly 260 brave men from different parts

of Illinois who attended. Twenty-three of these were from Alton, and

Major Charles W. Hunter (Alton developer and business man) was first

on the list. Their proceedings were broken up the first day by a

pro-slavery mob. A trustee from the church sent a note, requesting

them not to reassemble there, in fear that the church would be

destroyed. The next day, the convention met in the home of Rev.

Thaddeus B. Hurlbut in Upper Alton (this rock home still stands

today, at the southeast corner of College Avenue and Clawson

Street). The mob from the previous day went there, armed with bowie

knives, sword canes, and pistols. Illinois State’s Attorney Usher Ferguson

Linder (1809-1876) led the mob, which filled the yard, pounding on the door and

pressing their faces against the windowpanes. Rev. Hurlbut told them

they couldn’t come in, unless they broke in. Linder replied, “We

will break your damned head.” “Very well, said Rev. Hurlbut, “you

can do so if you choose, but you cannot come in.” The mob continued

threatening, while those within continued their business. The mob

decided to meet at a nearby schoolhouse to debate what their next

action would be. Someone (not identified) spoke out from the crowd,

saying “There are sixty armed men in the house!” This seemed to

dampen their enthusiasm. The next day the owner of the house

requested Rev. Hurlbut to meet elsewhere, so he fitted up a log

cabin that stood on his own property, and the convention continued

to meet there.

Colonel Charles W. Hunter and the

Liberty Party

Colonel Charles W. Hunter (he was often referred to as Major) was a

prominent Alton land owner and business man. He was a firm

anti-slavery man, and was a conductor on the Underground Railroad,

and attended the Anti-Slavery Convention of 1837 in Upper Alton. In

1844, Colonel Hunter was nominated as the Liberty Party’s candidate

for Governor of Illinois. The Liberty Party was firmly anti-slavery,

and its members were drawn from the Whig ranks. Unfortunately, Hunter lost the

nomination, and the Democrat won the governorship of Illinois.

In the Courts

In 1843, a case was brought before Judge Shields and jury. In Jarrot

vs. Jarrot, a French slave named Joseph Jarrot, alias Peter, who

claimed to be free, and sued his mistress, Julia Jarrot of Cahokia,

for pay for his past services. Joseph’s mother, Pelagie, was

purchased at four years of age, together with her mother, Angelique,

by Nicholas Jarrot of Cahokia, from one Le Brun, in 1798. Angelique,

the grandmother of Joseph, had been owned and held as a slave by the

father-in-law of Le Brunn, one Joseph Trotier, before the United

States took possession of the Illinois Country. Joseph Jarrot, who

was a descendant of a typical French slave, was bequeathed in the

will of Nicholas Jarrot, dated February 6, 1818, to Julia Jarrot,

the appellee. The case was first tried in the Circuit Court of St.

Clair County, when it was decided that a slave could not sue his

master for wages. The Supreme Court, however, reversed this in 1844,

declaring that “a colored person may maintain an action of assumpsit

for services rendered, and in such action his right to freedom may

be tried.” The Supreme Court decided that “the

descendants of the slaves of the old French settlers, born since the

Ordinance of 1787, and before or since the adoption of the

Constitution of Illinois, cannot be held in slavery in this State.

The effect of this decision was fortunate for the slave. It gave him

the right to sue for his freedom in the courts, and rendered the

holding of any negro indentured servants within the State illegal.

In 1854, the Illinois Legislature wiped out from Statute books the

infamous “Black Laws.” They had been legally in force in the State

for forty-six years. Following the Illinois Supreme Court decisions

of 1843 and 1845, there were three classes of negroes: indentured

servants (those serving out a limited period of time); French slaves

(a few negroes bound to perpetual servitude); and the free black

people. Although the poor black citizens were free, Illinois

residence was not without its drawbacks. Public office was closed to

them, as well as (for the most part) schools and colleges. There

were few trades or lines of employment that were easy to secure work

in. Intermarriage between the black people and white people was

forbidden under severe penalty. When in 1825 the Illinois

Legislature decreed that a common school should be established in

each county, it was open to every class of white citizens between

the ages of five and twenty-one. From that time until 1872, the

public schools were for white children only. There were exceptions,

however. The public schools in Alton accepted every child of

suitable age to school. However, in 1897, Alton officials erected

and opened two schools specifically for black students, which was

taught by black teachers.

State Convention of Colored Citizens of

Illinois

To Repeal the “Black Laws” of Illinois

Held in Alton, November 13 – 15, 1856

A convention of African-American men of the State of Illinois,

called for by the Central Committee in Chicago, was held in the

“Colored Baptist Church” of Alton, November 13 – 15, 1856, to

exercise their Constitutional right that was guaranteed to all

people, to peaceably assemble and to petition the government for a

redress of grievances. There were laws in the State they considered

disgraceful, and should be erased and blotted out from history’s

memory. The laws referred to were:

1. Taxation without the right to vote.

2. Denied the right to testify against a white man before a court of

justice.

3. Taxed for school, without the privilege of sending their children

to public schools.

Members of the convention of Madison County were: C. C. Richardson,

J. Kelley, Louis Overton, E. White, E. Wilkerson, H. Douglass King,

Rev. R. J. Robinson, and J. H. Johnson.

It was determined at the convention to form the “Illinois State

Repeal Association,” with appointed officers for a president,

vice-president, treasurer, secretary, corresponding secretary, and

an executive committee of nine. The object of the association was to

obtain all the rights and immunities of citizenship. Anyone could

become a member by paying an initiation fee of twenty-five cents.

Meetings were to be held on the second Thursday of each month. All

meetings were opened with prayer, and previous minutes read. The

following officers were elected: President – John Jones of Cook

County; Vice-President – Dr. M. Cary of Cook County; Secretary – B.

L. Ford of Cook County; Corresponding Secretary – John A. Crisup of

Cook County; Treasurer – William Jackson; and Executive Committee –

R. H. Rollins, Chicago, H. D. King, Alton; Thomas Mason, Peoria;

Louis Isbel, Chicago; Henry Bradford, Chicago; J. H. Barquet,

Chicago; William Johnson, Chicago; William Barton, Macoupin; and B.

Henderson, Jacksonville.

On the evening of November 15, A very large assemblage of both

colored and whites convened at Liberty Hall in Alton, to hear

speeches. Mr. Jones stated, “I am no public speaker; I am unsuited

to the platform. I am unsuited to the platform. If there is a place

for so humble an individual as myself in this anti-slavery movement,

it is the executive department. But I have had no choice in the

present arrangement; if so, I had not been here tonight; at least in

this position. The scene before me calls up old and familiar

reminiscences. I am no stranger here in Alton. I love it, because it

was here I first breathed free air and stood up a man, beyond the

reach of the inhuman code of slavery.”

Mr. William Johnson addressed the audience, then Mr. H. Ford

Douglass was introduced. He gave a lengthy, eloquent speech, part of

which is: “Judge Kane decided that a slaveholder had the same right

to carry his slave with him into a Free State, that he had to take

his carpetbag. The doctrine that Slavery goes wherever the

Constitution goes is now openly maintained by Toombs and others in

the South, and dough-faces innumerable in the North. This is the

only consistent course for the man who admits the constitutional

right of the slaveholder to make merchandise of men. If it permit

slavery to exist in Missouri – the right of one man to enslave

another; if it sanctions that infernal doctrine that had its birth

amidst the darkest conceptions of atheism – that one man can own the

blood, bones, and muscles of his fellow-man; traffic in the

blood-bought image of Christ; shut out from their immortal souls the

light of God’s glorious sun, then indeed is it a national

institution, having rights in common with any other institution in

the country, that the Constitution recognizes, to go wherever it

goes. But sir, I do not assent to the doctrine. This is not a great

slave empire – a barbarian people – third-rate civilization. To

borrow the undying inspirations of another, like the Roman who

looked back upon the glory of his ancestors, in great woe

exclaiming, ‘Great Scipio’s ghost complains that we are slow, And

Pompey’s shade walks unrevenged among us.’ ….. Let us profit from

the teachings of history, until each one of us shall fully realize

the truth of which Lord Bacon taught that ‘Knowledge is Power.’”

The State Repeal Association was formed with the following preamble:

“Whereas, We the people of color of the State of Illinois, are

cursed by the blighting influence of oppression, as displayed in the

inequality of its laws, in depriving us of the rights of oath and

franchise. And whereas, we believe these laws to be morally wrong

and impolitic. Therefore, we deem it our duty to organize

associations to employ all lawful and honorable means for the repeal

of the Black Laws of the State, and for the final accession of our

political rights.”

*******

The proceedings of the 1856 State Convention of Colored Citizens.

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863

The campaign of 1856 in Illinois proved to be the welding of all the

anti-slavery elements firmly into one organization, which in time

became the State Republican Party. Men with undoubted anti-slavery

principles, such as

Abraham

Lincoln, were chosen as its leaders. During the Civil War, on

September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued a preliminary

Emancipation Proclamation,

freeing more than three million slaves in the Confederate States, as

of January 1, 1863. The bold move recast the Civil War as a struggle

against slavery. Lincoln stated, “I never in my life felt more

certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper.” The

proclamation applied only to the States that had seceded from the

Union, leaving the slavery of 500,000 African-Americans in the loyal border States unaffected. It also exempted those

parts of the Confederacy under Northern control.

Abraham

Lincoln, were chosen as its leaders. During the Civil War, on

September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued a preliminary

Emancipation Proclamation,

freeing more than three million slaves in the Confederate States, as

of January 1, 1863. The bold move recast the Civil War as a struggle

against slavery. Lincoln stated, “I never in my life felt more

certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper.” The

proclamation applied only to the States that had seceded from the

Union, leaving the slavery of 500,000 African-Americans in the loyal border States unaffected. It also exempted those

parts of the Confederacy under Northern control.

The Emancipation Proclamation provided for the recruitment of

African-American

military units among Union troops. Tens of thousands of ex-slaves

volunteered for the armed forces. About 180,000 African-Americans

served in the U.S. Army, and 18,000 more in the U.S. Navy during the

Civil War. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered in November 1863,

referred to the proclamation and abolition of slavery as a goal of

the war with the words “a new birth of freedom.”

It was the

Thirteenth Amendment, passed in 1864, that outlawed

slavery throughout the United States. However, it did not confer

rights of citizenship. Full citizenship was granted to all African

Americans in 1868 with the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution, but it would be almost another 100 years before

African Americans were accorded full protection under the law, and

discrimination outlawed.

Modern Civil Rights for

African-Americans

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, requested by President John Kennedy

and pushed on by President Johnson, prohibited discrimination on the

basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, and was the

nation’s benchmark civil rights legislation. Civil rights leader,

Martin Luther King Jr., stated that the Civil Rights Act was nothing

less than a “second emancipation.” The act was later expanded to

bring disabled Americans, the elderly, and collegiate athletics

under its umbrella. It also paved the way for two major follow-up

laws: the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited literacy tests

and other discriminatory voting practices, and the

Fair Housing Act

of 1968, which banned discrimination in the sale, rental, and

financing of property.

********

Recommended Reading:

“Eyewitness Account: The Kidnapping of Africans for Slaves”, by Dr.

Alexander Falconbridge, 1788

*********

Sources: