Old Settler's Stories

The following articles (in chronological order, and totaling 245 pages in

my Word document),

taken mostly from the Alton Telegraph, were transcribed over many

years of research. The dates of the articles range from 1853 to

1949, and more may be added as they are found. These old

settlers' stories are priceless, in that they are in the words of

those who were in Madison County in its early founding, and tell of

the hardships and way of life they experienced. I hope when you read

them you will learn more of Madison County’s fascinating history.

Beverly Bauser

Madison County ILGenWeb Coordinator

NEW MADRID EARTHQUAKE

By Professor P. S. Ruter, Virginia Physician

Source: Alton Telegraph, April 27, 1849

From the Chronicle of Western Literature

A comparatively small number of persons now living can remember the

great earthquake of 1811. Few were in such part of the country, as

from their proximity to the scene of terror, to realize in their own

experience even the general accounts of the phenomenon, now found in

geographies and histories of the West.

Though the noise and agitation of the ground was heard and felt as

far northward as St. Louis, eastward to Cincinnati, southward to

Natchez, and further westward than the white man ever lived, yet, as

the violence and fury of the convulsion were concentrated near one

particular part of the Mississippi Valley, some thirty or forty

miles West of the village of New Madrid, Missouri, and as that whole

region of country was but thinly settled; moreover, as most of the

inhabitants around New Madrid were French immigrants, a great

portion of whom, having lost cattle, houses, and even families by

the earthquake, returned in despair to Canada – for all these

reasons, it is rarely that you can meet at this day, even among the

old men of the Western country, one who can give you any personal

recollection of the terrible night of December 24, 1811.

Geographies, histories, travelers’ notes, &c., tell of the strange

and dreadful changes wrought in the whole face of the country on

that most fearful night – of the huge chasms, still remaining and to

be seen in the southeastern Missouri, running northeast and

southwest, at right angles to the apparent path of the earthquake.

They describe how, for many miles, the banks of the Mississippi

caved and fell in, while the bed of the river rose so high at one

place that for six hours, the great Father of Waters flowed

northward toward his sources. How, at another place, near New

Madrid, a fall or cajaract [sic] of six or eight feet was created,

which remained for several days, till the current washed it level.

How, in northwestern Tennessee, what was once the bed of a lake,

level with and supplied from the channel of the Mississippi, became

what it now is, an elevated and beautiful prairie. How, for miles,

the channel of the St. Francis River was utterly and permanently

changed. How the islands in the Mississippi River did not escape the

general convulsion – some sinking, others and new ones rising; some

being split in two, as for instance Island No. 10, of which the

middle sank so deep, that for years the main channel of the river

ran through the gap. How Island No. 3 experienced a complete

_________ - the largest trees being found roots upward, in which

position they remained to the terror and destruction of steamboats,

until recently the most dangerous of them have been removed by

Captain Shreve, with the U.S. snag boats.

But nothing I have ever yet seen in print has equaled my own

recollection of the occurrences of that dreadful night. It is

possible that the exciting circumstances under which I was witness

to the scenes of the earthquake, added both to its peculiar terrors

and to the effect they would naturally produce upon anyone; but of

this the readers can judge, for I am going to describe them.

Graduating in the Spring of 1811 at the Medical University of

________, and returning home, I was during some months hesitating in

what part of the country to locate, for the practice of my

profession. The East was already tolerably stocked with physicians,

but the West, even at that early day, was opening its “El Durado

stores of promised wealth to the adventurer in almost any profession

or occupation. And though the privations and self-denial of frontier

life were little to my taste, I determined at least to visit before

fixing my choice elsewhere, this new land of promise, which, if not

like the fabled Pactolus, washing golden sands, was still believed

to be almost literally flowing with milk and honey.

OLD TIME STORIES

By One Who Was There

Source: Alton Daily Telegraph, April 6, 1853

"I find that the early history of Madison County is becoming lost in

oblivion. The first paper published in Madison County was the

Edwardsville Spectator, established in 1810 by Mr. Hooper Warren,

and conducted by him with considerable ability for six years, when

it passed into other hands, and at the close of its seventh year,

was discontinued – not from want of patronage, but because its owner

did not choose, and its printer was not able, for want of capital,

to continue it.

In 1821(?), Mr. Edward Breath, now in Perrin, Illinois, commenced

the publication of a paper at Upper Alton, from which it was

removed, as soon as an office could be procured, to Lower Alton, now

the city of Alton. That office was in the upper story of the first

warehouse built west of Piasa Creek, by James S. Lane, and which

Messrs. Bruner tore down last summer to put up their fine warehouse.

Having acquired his trade in the office of the Edwardsville

Spectator, and admiring the principles on which that paper had been

conducted, as well as the integrity of his former “boss” (Mr. Hooper

Warren), Mr. Breath gave his paper the name of the Alton Spectator,

under which name it gained quite a reputation, both for editorial

and mechanical ability. For a short time, at first, Mr. O. M. Adams

was connected with the enterprise. I do not remember how long Mr.

Breath continued the Spectator, but although its prospects were

good, the want of present capital was so embarrassing that he sold

the establishment, and from a Whig it became a Democratic paper

under the editorial conduct for a while of Mr. Hudson, and then of

Dr. Hart. It was, I think, while the latter gentleman conducted it –

and it was then ably edited – that Messrs. Treadway & Parks started

the Alton Telegraph, which the present senior not long after

purchased, and has continued ever since to conduct with his

well-known ability.

I know but little of subsequent attempts – more than that such

attempts have been made – to get up papers in Alton, but there is

another old time that which ought not to be omitted. During the

“convention struggle,” which commenced in the session of 1822-1823,

and continued to the election in August 1824; and which was an

attempt to get up a Convention for the purpose of introduction

slavery into our State, another paper – I forget its title [editor’s

note: the name of the paper was the Star of the West] – was started

in Edwardsville, and edited by the late Judge Theophilus W. Smith.

The contest between the prominent lawyer and the unpretending

printer was quite interesting. There were several other papers to

the State engaged on both sides of the question, but none perhaps

with more vigor and talent than these. The National Intelligencer

said at the close that “the question of Convention or no Convention

in Illinois is decided in the negative, after as thorough a

discussion as any subject ever had.” In fact, both parties gained

their object – slavery was kept out, and its advocates got all the

offices.

Signed by One Who Was there,Up the River, March 23, 1853."

REPLY TO “OLD TIME STORIES”

Written by “O”

Source: Alton Daily Telegraph, April 16, 1853

“One who was there” very justly remarks that “the early history of

Madison County is becoming lost in oblivion.” This may, however, be

prevented if those early settlers of the county who still remain

among us will at once communicate to the newspaper press their

recollections of events which happened in the infancy of our county.

I came to this county in 1817, the year before Illinois became a

State. Of course, there are many who can relate much earlier events

in our history than I can. In regards to the early newspaper

establishments in the county:

1. The “Edwardsville Spectator” was established in the summer of

1819 at Edwardsville, by Mr. Hooper Warren, who conducted it five or

six years, and transferred it to Messrs. Lippincott & Abbott. It was

a few years afterwards discontinued. Mr. Warren was recently, and

probably still is, a resident of Marshall County, Illinois.

2. The “Star of the West” was established at Edwardsville by Messrs.

Miller & Stine, in 1822.

3. In 1823, the last-named establishment passed into the hands of

Messrs. Thomas J. McGuire and Co.; the name of the paper was changed

to the Illinois Republican; it was edited by the late Judge Smith,

and devoted to the support of the Convention question, which was

warmly agitated in 1823-24.

4. In 1830, a paper called “the Crisis,” was published in

Edwardsville by S. S. Brooks, Esq.

5. In 1832, the “Illinois Advocate” was published in Edwardsville by

John York Sawyer, Esq. This paper was afterwards published at

Vandalia, where Judge Sawyer departed this life.

6. A paper was afterwards published at Edwardsville by the late

James Ruggles, called, if I rightly recollect, the “Weekly Western

Mirror.”

7. After an interregnum of some duration, the “Madison County

Record” was established by Messrs. Smith & Ruggles – being the

seventh and last establishment of the kind at our venerable county

seat. This paper has recently become merged in the Alton Telegraph.

At Alton, the first paper established was the “Alton Spectator,”

commenced at Upper Alton in 1831 by Mr. Edward Breath, now in

Perrin. It was afterwards removed to Alton city, and after Mr.

Breath disposed of it, it passed through a variety of hands, and

finally died out.

The second paper at Upper Alton was the “Western Pioneer,” published

in 1836, 1837, and 1838 by Ashford Smith & Co.

The second paper established in Alton city was the “Alton

Telegraph.” In 1836, by Messrs. Treadway & Parks. In 1837, Mr.

Treadway having deceased, the present Senior Editor became connected

with the establishment. The Telegraph has been continued more than

17 years, and is, I believe, the oldest paper in the State.

Several other papers, I believe, have been started at Alton and

continued but a short time. Their names, and those of their

publishers, have escaped my memory. Some historian of Alton will

doubtless interfere to prevent them from being lost in oblivion.

The last paper is the “Alton Courier,” established about the

beginning of 1852 by G. T. Brown & Co. This promises to be more

permanent than its predecessors of the same party have been.

Somewhat over two years ago, I read in some paper (I think the

Madison County Record – a kind of supplement to the Census of

Madison County) in which an attempt was made to state who were the

“first settlers” in each of the towns in the county. The name of

Colonel Rufus Easton was given as the first settler of Alton; that

of William Collins as the first settler of Collinsville; and Messrs.

David Hendershot and James Riggin were named as the first settlers

of Troy. In all these cases, the statement was incorrect, unless a

very unusual definition is given to the word settler.

Alton - Colonel Easton was the founder and proprietor of Alton, but

he never resided there. St. Louis was the place of his residence,

though I believe he removed to St. Charles before he died. Who was

the first settler – that is, the first man who resided on the land

now occupied by the city of Alton – is more than I can tell.

Collinsville – Section 34, township 3 north, range 8 west (the land

on which the old part of Collinsville was located) was entered at

the Land Office by Messrs. Augustus and Anson Collins, on January

9(?), 1818. They soon commenced improvements thereon; and were

joined by two of their brothers, Messrs. Michael and William B.

Collins. A town was laid out and named “Unionville.” In the fall of

1822, Deacon William Collins, the father of the gentlemen already

named, with his wife, one son, and three daughters, emigrated to

Unionville, the name of which was then, or soon afterwards, changed

to Collinsville. Who was the first settler of Collinsville I am

unable to say with certainty. I have understood, however, that the

late John Cook resided upon the townsite before it was purchased

from the United States, and that the Messrs. Collins paid him for

his improvements.

Troy – Messrs. Hendershot and Riggin were the founders and

proprietors of Troy. They gave it that name, it having previously

been called Columbia. Mr. Riggin resided in Troy, and was therefore

a settler, but if my memory serves me, other persons settled upon

the townsite before he did, and therefore he could not properly be

styled the first settler. Probably he was one of the men who were

settled upon the townsite when it received the name of Troy. Mr.

Hendershot once resided in the vicinity of Troy, but never in the

town. He was, therefore, not a settler of Troy, in the usual

acceptation of the term. The northeast quarter of Section 9,

township 8 north, range 7 west (on a part of which stands the town

of Troy) was entered at the Land Office by the late John Jarvis on

September 10, 1814. Signed “O.”

OLD SETTLER

By Moses Lemen

Source: Alton Weekly Courier, December 6, 1855

To the editor of the Courier: “I do not know that I have ever had a

personal introduction to you, a thing that would please me much, but

I have seen and read several numbers of the Alton Weekly Courier,

and can say that I am well pleased with its spirit, matter, and

politics, and hope it may find a wide circulation and substantial

patronage. I wish to become a subscriber.

If you wish, I will furnish for your paper some sketches of Indian

eloquence and oratory, savage cruelty, exploits of backwoods

huntsmen, in pursuit of the wild stag, bear, and wolf, and now and

then an anecdote on marriage customs in Illinois.

You are fully aware of the responsibility of that man who fills the

editorial chair. That the world is letting go of books and taking

hold of newspapers as a medium of information, is manifest to every

observer. Newspaper reading is bound to mould the character of the

rising generation to a great extent, and its influence for weal or

for woe is yet untold. How important, then, that an editor should be

a man of integrity, veracity, and talent. Many of those who have

conducted the press, heretofore, have done so to promote the

interest of some political party or demagogue, and by so doing have

traduced and aspersed the characters of many worthy citizens, the

public peace destroyed, and the cause of truth injured. Many of

those who profess the religion of the meek and lowly Savior have

dipped their pen so deep in gall, and have exhibited such a spirit

of war, that a savage from the wilderness has been induced to send

them a battle axe. Think it not flattery sir, when I say the Courier

is a sheet of truth.

'Truth crushed to earth, will rise again;

The eternal years of God are hers;

While error wounded, writhes in pain,

And dies amid her worshippers.'

My place of address is Walshville, Montgomery County, Illinois.

Signed, Rev. Moses Dodge Lemen."

EDITOR’S NOTE:

The following 43 articles, titled "Early Days in Madison County,"

were written by Reverend Thomas Lippincott from August 26, 1864 to

July 28, 1865. Reverend Lippincott (1791-1869) settled in

Edwardsville in 1818, and was a strong foe of slavery. He was active

in opposing the adoption of a pro-slavery constitution for Illinois

in 1824. In 1825-26 he edited, in association with Hooper Warren,

the Edwardsville Spectator. He then became a minister of the

Presbyterian Church and associated himself with its activities

throughout Illinois. When he first came to Madison County, Illinois, he operated a general store in the

town of Milton, between present-day Alton and East Alton. Reverend

Lippincott wrote these articles at the request of Willard C. Flagg,

Secretary of the Madison County Historical Society.

Annotations by George Churchill

George Churchill’s career paralleled Thomas Lippincott's, who

assisted Hooper Warren in editing the Edwardsville Spectator,

1819-25. Churchill actively opposed the pro-slavery movement in

Illinois, and served in the Illinois General Assembly, 1822-32, and

1844. Because he voted against the resolution for a convention to

revise the constitution in favor of slavery, he was burned in effigy

at Troy by pro-slavery constituents. Included below are some of his

annotations concerning Reverend Thomas Lippincott's “Early Days in

Madison County.”

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO. 1

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: Alton Telegraph, August 26, 1864

"I was very imprudent to allow myself to be beguiled into a sort of

a promise to call up the memories of the years that are long past. I

am in the predicament of him who boasted to Hotspur that he could

“call spirits from the vastly deep,” when the spicy gentleman

significantly asked, “But will they come, when you do call them?” I

am afraid not, very readily, and not very regularly, yet I will try.

I came to Madison County in the Autumn of 1818. In fact, it was the

first day of winter when I arrived with my family to reside. But it

may not be intolerable in an old man’s story to go back a little and

tell how it happened.

I feel inclined to copy the minute made by me in regard to one

place. We had descended the Falls in an oar boat during a heavy rain

and fog, and our women and children and beds were very wet. In

consequence, we went ashore to obtain lodging for the folks while we

could dry the bedding, and were hospitably and kindly entertained by

Mr. Nathaniel Scribner, one of the proprietors of the town, with

whom my wife had been formerly acquainted. After leaving, I wrote

thus: “New Albany is pleasantly situated on the right bank of the

Ohio River in Indiana, and in my opinion, bids fair to become a

place of great business. Enterprise is a characteristic of the

proprietors, and many lots have been sold. There are at present,

ninety families (Mr. N. Scribner informed me) in the place, some

good frame houses, a number of log dwellings, an elegant brick house

and store, owned by Mr. Paxson, late of the house of Lloyd, Smith,

and Paxson of Philadelphia, and a steam mill, driving two saws and

one run of stones. Two steamboats are on the stocks, and three more

are to be shortly put up. A ferry, having a great run of business,

is established here.” Such was New Albany, and such its prospects,

as they appeared to me on Christmas Day, 1817. I have never stepped

on its shore since, and cannot, therefore, describe its present or

foretell its future, except from the current history.

On landing at Shawneetown, we found a village not very

prepossessing, the houses, with one exception, being set up on posts

several feet above the earth. The periodical overflow of the river

accounted for this, and I imagine the exception, a brick house, was

hardly as agreeable residence when the inhabitants went from house

to house in boats (an annual occurrence) as the less pretentious log

dwellings.

After a detention of several weeks at Shawneetown – while we were

told the roads were impassable on account of mud – a hard freeze and

storm covered the face of the earth with solid ice, and procuring a

horse, I set out with my family and my “plunder,” as the people

along the road would call it, in a little Dearborn wagon, to cross

the country to St. Louis, leaving my companions at Shawneetown. The

_____ on which we started became slow, as we advanced, and we waded

through it slowly, wearily, from the 6th to the 17th of February

1818, except two days spent in the kind and hospitable family of

Judge Lemen, at New Design, near where Waterloo now is, when we saw

and crossed the majestic Mississippi, and for a few _____ are

residents of St. Louis.

Such was traveling in the Territory of Illinois. The road a mere

path, and thro the woods indicated by “three back” trees. The only

towns or villages that we saw were Kaskaskia, the seat of the

Territorial government, and Prairie de Rocher, a few miles from St.

Louis. It will take another paper to get me over to Alton.

I arrived at Louisville, Kentucky, February 15, 1817, and left for

St. Louis, June 5, on the keelboat Dolphia, Captain Billings. During

my stay at Louisville, I worked at the printing business, a part of

the time in the office of the Louisville Courier, published by N.

Clarke, and another part of the time in the office of the

Correspondent, published by Elijah Berry, afterwards well known as

the Auditor of Public Accounts of the State of Illinois."

Annotation by George Churchill:

"Mr. Lippincott’s mention of Mr. Paxson reminds me that during my

stay at Louisville, a Mr. Paxsen was drowned in a creek a few miles

from New Albany, Indiana, while attempting to swim his horse across

the same, when the water had been swelled by a sudden freshet. Such

disasters were of frequent occurrence in the “early days” of the

West, when bridges were few and far between. Our own Birkbeck lost

his life in a similar manner."

Continuation by Rev. Lippincott: "When the Dolhin arrived at

Shawneetown, June 11, my fellow traveler, Mr. Kersey Jones – a

tanner from Pennsylvania - and myself, concluded to leave the boat

and walk across the country to Kaskaskia. Shawneetown is described

in my diary as “a village of about forty houses; no fields, gardens

or orchards are to be seen here.” We left Shawneetown on June 11,

and reached Kaskaskia on the 16th, tired and footsore. We put up at

the hotel of Mr. William Bennett. Mr. Bennett was a Pennsylvanian.

He has since resided in Madison County and in Galena, and was the

father-in-law of the late Guy Morrison of this county. This hotel

appeared to be the rallying point of most of the Territorial

officers, such as Governor Edwards, Secretary Phillips, Delegate

Pope, and Colonel Michael Jones of the Land Office. The latter took

a fancy to my fellow-traveler, claimed him as his nephew, and

offered to set him up in business if he would stay. But Kersey Jones

disliked the country, would go and look at Saint Louis, and then

return to Pennsylvania. We stayed six days at Kaskaskia, then

proceeded to Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, where we learned that the

Dolphin had left the landing only an hour before. We walked up the

riverbank about two miles, overtook the boat, got on board, and

arrived at Saint Louis on June 27, 1817. We put up at the Green Tree

Inn, kept by Daniel Freeman, formerly of Dover, New Hampshire.

Travelers by steam at the present day will look with wonder on the

record of journeys made forty-eight years ago."

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO 2

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: Alton Telegraph, September 02, 1864

"In a few days after my arrival in Saint Louis, I was employed for a

little while to do some writing for Rufus Easton, Esq., a lawyer of

wealth and prominence in the Territory of Missouri, of which he had

been the delegate in Congress. One of the jobs executed by me for

him was making a fair copy of a plat or map of Alton, a town which

he had laid out the previous year on the banks of the Mississippi in

Illinois. This map was designed for exhibition at the East, in order

to effect the sales of lots. I took some pains to make it look well,

and I believe, gave satisfaction.

After a few months spent by me as clerk in a store, Colonel Easton.jpg) proposed to me that I should take a stock of goods, in partnership

with him, and keep a store at Alton or neighborhood, and accordingly

I became a resident as before said in Illinois – now became a State

– on December 01, 1818. It was not in Alton that my store was

opened. Alton was in embryo. When Colonel Easton brought me first in

his gig to see the place, there was a cabin not far, I should think,

from the southeast corner of the penitentiary wall, or corner of

State and Short Street, occupied by the family of a man whom the

Colonel had induced to establish a ferry in competition with

Smeltzer’s ferry, a few miles above. I forgot the name of this

ferryman, and indeed the names of almost everybody else then extant

(which is the reason why I said it was imprudent in me to attempt

these sketches), but his habitation was about as primitive and

unsightly as I had seen anywhere. I do not think he was overworked

by the business of his ferry at that time, for the old road passed

north and out of sight, and it was not easy to persuade travelers to

try the new one, even if they ever heard of it, which was probably

rather seldom.

proposed to me that I should take a stock of goods, in partnership

with him, and keep a store at Alton or neighborhood, and accordingly

I became a resident as before said in Illinois – now became a State

– on December 01, 1818. It was not in Alton that my store was

opened. Alton was in embryo. When Colonel Easton brought me first in

his gig to see the place, there was a cabin not far, I should think,

from the southeast corner of the penitentiary wall, or corner of

State and Short Street, occupied by the family of a man whom the

Colonel had induced to establish a ferry in competition with

Smeltzer’s ferry, a few miles above. I forgot the name of this

ferryman, and indeed the names of almost everybody else then extant

(which is the reason why I said it was imprudent in me to attempt

these sketches), but his habitation was about as primitive and

unsightly as I had seen anywhere. I do not think he was overworked

by the business of his ferry at that time, for the old road passed

north and out of sight, and it was not easy to persuade travelers to

try the new one, even if they ever heard of it, which was probably

rather seldom.

Let me tell a few things about the origin and early years of Alton.

In the first place, Colonel Easton laid out in 1817 or before the

town fronting on the Mississippi River, consisting of the streets

between and including, I believe, Henry Street on the East, and

Piasa Street on the West. I do not remember how far north it

extended, but think not further than Tenth Street. This may not be

correct, and if the original plat, or boundaries, can be found,

which is doubtful, it might be interesting to the curious to

ascertain the facts. I know the valley, now the east part of town,

was not in the first map. The town immediately had a rival. Mr.

Joseph Meacham laid out Upper Alton, and published it abroad as if

it were part of Alton, but on the hill. I believe purchasers

discovering that it was 2 miles away from the landing expressed

dissatisfaction; whereupon Mr. Meacham purchased what was called the

Bates farm, laid it out, and advertised it as Alton On the River.

This last enterprise was purchased by Major Charles W. Hunter,

perhaps in 1818, and has since been popularly known as Hunterstown,

and has very properly been incorporated into the city of Alton. I

did not, in those days, expect to see the three separate enterprises

united as they now substantially are, into one thriving business and

commercial place.

Litigation kept Alton from improving some ten or twelve years.

Several of the leading lawyers of Illinois purchased or possessed a

title adverse to that of Colonel Easton, to the land on which he had

laid out his town. Such men as Ninian Edwards, the Territorial

Governor, Nathaniel Pope, so long the able District Judge, and

others, would bring wealth, legal talent, and perseverance into the

conflict, and Colonel Easton had them all to contend against. Of

course, no permanent improvements, nor extensive purchases would be

made while this contest was going on. I know not who had the right,

or the law in the case, nor do I believe anybody else ever knew, and

when the parties got tired of their unprofitable contest, they

compromised by dividing the land. Of this division, I only know that

Edwards, Pope, and Co. got some of the northern portion, and laid

out some beautiful lots which are now occupied by the elegant houses

of Mr. Bowman and others, on a line with the Cumberland Presbyterian

Church. This difficulty being removed, improvements began to be

made, and the village of Alton began to be. But I must go back and

tell a little – all that I can remember – of the day of a small

thing."

Annotations on Lippincott’s No. 2 by George Churchill

"It was either in 1818 or 1819 that I attended at Colonel Easton’s

Alton, where the proprietor was to offer some of his city lots for

sale, and for that purpose, displayed a beautiful map, which had

been prepared in accordance with this advice of one of the posts of

that day:

The most important point, perhaps lies in the drawing of the maps,

The painter there must try, By mingling yellow, red and green,

To make the most delightful scene, That ever met the eye.

There were Gospel Lots, an Observatory Square, College Lots, and I

know not how many other reservations for public and charitable

purposes, delineated on the map. The company was not numerous, yet

two gentlemen from the State of New York were there, viz: Mr. Reuben

Hyde Walworth, afterwards Chancellor of the State of New York ___

____ ____ [unreadable] think no lots were sold. There were three or

four buildings east of Little Piasa, but no improvements west of

that stream.

In the latter part of 1819 and the forepart of 1820, John Pitcher

advertised that he kept the Fountain Ferry. His advertisement was

succeeded in the Edwardsville Spectator, on the February 22, 1820,

by that of Mr. Eneas Pembrook who added that he also kept a tavern.

Both the ferrymen advertised that the road from Milton, by Fountain

Ferry, to Madame Griffith’s near Portage des Sioux, is three miles

shorter than any other road now traveled between said places, and

that at Fountain Ferry a boat could cross three times in less time

than it could cross once at any other ferry on the same river in

this State. I know not at what ferry the immigrant for Boone’s Lick,

mentioned by Parson Flint, crossed the Mississippi, but when he got

into the Point Prairie, St. Charles County, Missouri, where the soil

is as rich as fresh soil can be, he dug up some of the black soil

and exclaimed: 'If the land is so rich here, what must it be at

Boone’s Lick!'

The Bates farm was afterwards called 'Hunterstown.'

Joseph Meacham laid out the town now called Upper Alton in 1817 or

before, upon land on which only one-fourth of the price had been

paid. He disposed of as many lots as he could by lottery. Each

ticket drew one lot, or a larger tract – say thirty acres, more or

less. These last were considered high prizes. In 1817, Meacham’s

Alton was far ahead of all the other Altons in population and

improvements. The people of the adjacent country were in the habit

of lumping them all together, and calling them 'Yankee All-town.'

At length, the owners of lots in Meacham’s Alton discovered that

they were in danger of having said lots forfeited to the United

States. To prevent this, they raised the necessary funds, cleared

the land out of the Land Office, and appointed Messrs. Ebenezer

Hodes, James W. Whitney, Erastus Brown, and Augustus Langworthy to

execute new deeds to those who held deeds from Mr. Meacham, on their

coming forward and exchanging their old deeds for new ones from the

above-named gentlemen. This was accordingly done, and one danger was

avoided."

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO. 3

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: Alton Telegraph, September 9, 1864

[Note: This article was extremely hard to read – there are

omissions, and possibly errors.]

"The stock of goods which Colonel Easton prepared to put in my

hands, and which ______ into Madison County, was to be ________ not

of a larger stock that he had ______ on point on the Missouri River,

which ______, and I hoped to make valuable as a ferry (called

Fountain Ferry), and perhaps a town. The Colonel had purchased a

large stock of merchandise and place it in the hands of Ebenezer

Huntington, a young man who had made extensive tours in the South as

a lecturer and de_____, with no little applause, and in the winter

of 1817-18, was starring it in St. Louis on the stage. It was soon

found that _____ and dollars’ worth of goods was too much to hold in

a place where there was nobody to buy – at least I saw no one _____

near there, and so the Colonel sent a part of it by me to be offered

for sale on the east side of the Mississippi.

Hawley’s store was not opened in Alton, ______ _____ there. Sometime

in November 1818, I stepped out of a keel boat on to the shore of

the Mississippi, and found _____ and my goods under a magnificent

grove of Sycamore or Cottonwood trees, _____ from the mouth of what

the _____ had named Fountain Creek, but which was, and is better

known as Little Piasa, _____ point where the bluff jutted on the

river, on which the old Penitentiary was afterwards built. I think

there was no house there then but the ferry house, and perhaps a

cabin on or near Second Street [Broadway], somewhere south of Alby

Street. The hills were crowned with lofty oaks, and formed, as they

do now, a splendid outlook over to Missouri and up and down the

river. Nature was in her own dress then.

There was a busy, active village even then in the neighborhood. A

firm, consisting of John Wallace and Mr. Seely, owned a mill site

three miles below on the Wood River, where they had three mills –

two saw mills and a grist or flour mill – and they were in full,

active operation. Messrs. Wallace and Seely had laid out a town and

called it Milton, and were doing a fine business. A distillery a few

rods up the Wood River was equally active. A. W. Donohue, a merchant

of St. Louis, had put up a building and opened a store at the bridge

in Milton, under the charge of Richard T. McKenney, but whether from

want of patronage or society, Mr. McKenney ____ before _____ ______

the store in St. Louis. He was afterwards teller and then cashier of

the Bank of Edwardsville, and was highly esteemed for his social

qualities and strict integrity. To this storehouse, by direction of

Colonel Easton, I brought the goods, and the farmers and travelers

(for there was a road there, and some travelers) could read the

sign, “Lippincott & Co.,” and if they chose, purchase dry goods and

groceries as cheap and as good, perhaps, as they can be had now in

these war times. I remember I sold coffee at fifty cents a pound,

and salt at three dollars a bushel.

A contract had been entered into by Colonel Easton with Daniel Crume

and William G. Pinckard for the erection of four log houses. I

believe hewn logs, on different parts of the town site. He

afterwards changed the plan so far as to unite two of these in one,

which was put up on the block between Market and Piasa and Second

[Broadway] and Third Streets. I believe that house (which was so

long occupied by Mr. Thomas G. Hawley) is still standing, though

surrounded by other buildings at least it was there until the brick

stores were put up in front of those I have mentioned the name of a

gentleman who has always been a resident of Alton, knows its history

much more perfecting, and would remember vastly better than I, and I

would suggest that one of the proprietors of the Alton Telegraph

could probably have access to him and to his more valuable

reminiscences. At any rate, I hope my old friend, William G.

Pinckard, will look over, correct, and complete the rambling

recollections of one whose memory is not only defective, but who is

so far away from the place and people of Alton as to have no means

of correcting errors, or help in recalling facts.

I have a very indistinct recollect, or imagination, of a row of

several small tenements strung along under the sycamores, sometime

in the winter of 1819-20, occupied by several families, whose names

I cannot recall (unless one of them was named Ward), who did not

remain long in the place or neighborhood. It was an ephemeral as

humble. But I seem to remember yard and garden fences in a small

way. It seems to me these cabins must have been under the first

bank, which was where Second Street [Broadway] is, west of Piasa."

Annotations on Lippincott’s No. 3 by George Churchill

"Walter J. Seely moved to Edwardsville, where he kept a public

house. He died January 13, 1823. The Star of the West said he was a

native of Goshen County, New York, probably meaning Orange County,

in which the town of Goshen is situated."

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO. 4

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: Alton Telegraph, September 16, 1864

"I do not get along fast. Three numbers only bring us to the winter

of 1818-19, and well little of that. No matter. When the reader gets

tired of the early days, or its old writer, he can skip the rest. Or

the editors can just cry 'hold, enough,' and the fountain will dry

up.

In order to draw travel, a road was necessary to Alton from Milton,

and to cross Shield’s Branch, a bridge was indispensable.

Accordingly, Colonel Easton made a contract with Joel Finch to build

a frame bridge, for which he was to be paid at my store, the sum of

two hundred dollars. The bridge was built about or very near the

site of the present covered bridge. One or two of the same kind

succeeded the original at almost the same price, before the present

structure was erected, the road wound somewhat through the Bottom,

but was soon run as now along the bluff. There were two families

residing between Milton and Alton – or more properly between the

Wood River and the Bates’ farm. The first, near Wood River, was

owned and occupied by a widow Meacham, who had been there during the

late war time – the War of 1812 – and as she told me, was visited by

Indians on the same night, I think, on which the Wood River Massacre

occurred. The old lady was highly esteemed, and I use to enjoy her

conversation much. She had two sons, men grown, and two or three

daughters, if I am not mistaken – one of whom was married to Mr.

Whitehead, afterwards a thriving and wealthy citizen of St. Louis,

and a L____ First Presbyterian Church. If I could talk awhile with

Squire Pinckard, I know I could tell a good deal more, and a good

deal better about some of the first families of that part of Madison

County. The other family on the road was that of Mr. James Smith,

nearer Alton. I only know of this family that Mr. Jubilee Posey

married a daughter, and that I often enjoyed their hospitality in

later years in the neighborhood of Troy, where Mr. Posey was a

thrifty and respected farmer.

I can now, familiar as they were to me and long remembered, call to

mind but few of the old settlers round Alton at that time. There

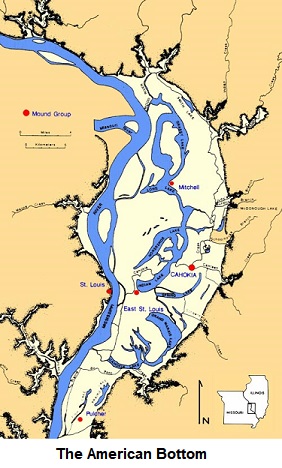

were besides others, two families scattered along the American

Bottom for some miles below Milton - the Gillhams and the Preuitts.

Gillham was the last Sheriff of Madison County under the Territorial

Government. He owned a fine farm and a ferry on the banks of the

Mississippi, opposite the mouth of the Missouri, most of, or at

least much of which farm I believe has gone down the river, perhaps

to the Gulf of Mexico. In the summer of 1818 or 1819 (I forgot

which), I saw several steamboats lying at the bank of Mr. Gillham’s

farm – more than I had seen at one time at St. Louis. They were

boats employed by Colonel James Johnson, brother to Richard M

Johnson, to carry supplies for up the Missouri to Fort Osage, on a

contract with the U. S. Government. I suppose such boats would be

considered small affairs now, but to me, and many who went to see

them, they were rather magnificent. The other Gillhams were settled

along near the Long Lake.

The Preuitts occupied farms along the bluff from the Wood River to

where the Edwardsville Road ascended the bluff at W. T. Davidson’s.

Abraham, William, and Isaac dwelt on the side of the bluff facing

the American Bottom, and Solomon somewhere on the table land above.

They have all been gone many years to Greene County, I believe. One

of them, Isaac, was distinguished as having been the only one who

killed one of the Indians who had massacred several of the Moore

family in the forks of the Wood River. The pursuit of the Rangers

was so hot, however, that it was believed none of the gang ever got

back to their tribe alive.

There was a farm and horse mill adjoining Milton, and several fine

farms strung along on the west side of the prairie some three or

four miles – some of them quite large and all productive. I have

since been passed over the same ground, and found it clear prairie.

The only indication of settlement being rows of cottonwoods forming

a hollow square, and showing where the fences of one of the farms

had been. These latter years have filled up this space with farms

again.

Above the bluffs, on the table land, I remember several farms which

were old settlements when I came to the country. In the forks of the

Wood River were three brothers by the name of Moore – George,

William, and Abel. The two latter had built them each a brick house,

but George still occupied the old log, considerably enlarged, and

near him still stood the blockhouse to which the inhabitants

resorted to in times of danger, and the powder mill in which they

were wont to provide themselves with ammunition."

Early Days in Madison County, No. 5

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: The Alton Telegraph, September 23, 1864

"The inhabitant of the settlement between the two branches of the

Wood River, if we may judge from a specimen, increased apace. I was

called in 1819, I believe, to marry a couple (for I received a

commission as Justice of the Peace within a few months of my arrival

at Milton) which was duly performed under the shade of one of the

monarchs of the primeval forest. Some years afterwards, I called to

see this married pair at their residence on the Woodburn Road, and

found them a well-to-do family, the parents in the vigor of life,

with sixteen children. I do not know that all the families were

equally prosperous, but the population and the farms multiplied in

that region.

I had occasion in that year to make a journey into the 'Sangamon

Country' (it was not yet in existence at that time). Starting from

Milton and ascending the bluffs a short distance from it, the road

skirted the Wood River timber on the south side, passing through

what was known as Rattan's Prairie [near Bethalto], and continuing

entirely in the prairie, after passing the head and timber of that

stream a mile to two, perhaps more united with a road that ran from

Edwardsville, and so passed North. The farm and house of Jesse

Starkey was the last we passed, as I remember, in that region.

Of the inhabitants of that prairie settlement, I can only remember

to name William Montgomery, Richard Rattan, Thomas Rattan, Rev.

William Jones and Jesse Starkey, aforesaid. There were others, one

especially, whose house I often passed in after years on the way to

Edwardsville, as well if not better known to me, but whose names I

cannot recall. These were all men citizens. I believe their

descendants are of substance, and have been prominent people of note

in this county or elsewhere at the present day.

In the journey I spoke of, we made many points. There were, after

leaving Wood River and launching out into the open sea (prairie) as

landmarks, first Dry Point, the head of the southern branch of the

Macoupin; then Honey Point, of the Middle Fork; then Slab Point, a

little off the road to the left; and next Lake Fork, at the head of

the northern branch. From this last the road struck across to Brush

Creek, and then to Sugar Creek, waters of the Sangamon River. We

staid all night at Honey Point at Mr. Robinson's (father-in-law to

George Debaun) and the only house between Jesse Starkey's in

Rattan's Prairie and a house on the waters of Sugar Creek, now in

Sangamon, but then in Madison County. Soon after (that same season

perhaps), Dry Point was occupied, I think by a Mr. Hammer, and Lake

Fork was improved by Mr. Henderson. As Mr. Henderson kept a very

comfortable and pleasant house of entertainment, at a point where

the roads from Edwardsville and Hillsborough (where that was built)

to the Sangamon Country, and afterwards Springfield, it became a

place of great resort and of course quite noted; but it seems to

have been known as Macoupin Point in those after years. The roads

being subsequently changed, Mr. Henderson removed his establishment

some years afterwards to the prairie where the roads from Madison

County to Springfield were crossed by the road from Hillsborough to

Jacksonville. After his death, this house was kept by his widow, and

then by his son-in-law, Mr. Virden; who, when the railroad (Alton &

Springfield) was located removed a few miles in sight of the old

place, and gave name to the flourishing village now well known as a

point on the St. Louis, Alton & Chicago railroad. But, I am getting

ahead of my story.

When I came to Milton there was a public house kept by Joel Bacon,

in a cabin near the bridge. In the summer of 1819, he erected a

frame house a little higher up, to which he removed his family and

tavern (it was not a drinking house) and entertained travelers as

comfortably as the circumstances of the country allowed. His wife

was a notable and very excellent woman, and his daughters and hers

all afterwards married, some in Greene and one in Pike counties,

aided in keeping a cleanly and respectable house. I boarded with

them in the cabin some weeks or months, until ready to occupy the

little room in the rear of my store.

I think it must have been in the summer (or spring) of 1819, that

Mr. Robert Collet, a merchant of St. Louis, bought out the interest

of Mr. Seely in Milton, and henceforth Wallace and Collett became

the proprietors of the village, the mill and the business of Milton.

Mr. Collett, however, kept the store - a rather extensive one for

the time. My store was separated from the rest of the house simply

by lathing. My residence was then in a little cabin near Mr.

Bacon's. That big house, after Mr. Bacon's death, being still in its

unfinished state, was taken down and taken up to Upper Alton, where

it was the residence of George Smith. Perhaps I ought not to omit so

trifling a circumstance as the gathering of about a dozen or twenty

children - all there were - into our house on Sabbath mornings for

religious instruction. My wife, who had had much experience and

success in teaching, could not be easy without the effort, and it

was made; - and thus, got the name of the first Sabbath School in

Illinois."

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO. 6

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: Alton Telegraph, October 7, 1864

"Dr. Langworthy was a man of some note in those days. My memory

fails me here again, not only with respect to his name, which I well

knew, but with regard to some other persons more or less connected

with him. Though I knew and respected them, I find it impossible to

recall enough about them to venture any mention of them. One man, of

a different class, must not be

There was another, and very different person on whom my mind loves

to dwell. Whether he was among us so soon as this, I am not sure.

Perhaps one of the editors of the Telegraph could ascertain and

tell. Rev. Nathaniel Pinckard, having preached the gospel as a

Methodist minister, in the traveling connection many years, settled

down at the late evening of life in the new and crude village of

Upper Alton. He had made the accumulations common to the calling:

experience, wisdom, the love of God, and his fellow men, the usual

infirmities of age, and _____ to toil for a living. His cheerful,

genial spirit and kindness of heart, rendered him very attractive to

me, and I believe to others. There was one tie that bound us

together even more than others – a strong sympathy and agreement on

the subject of slavery. My hatred of it was inherited, or at least

drawn with my mother’s milk. His was caused or intensified by actual

contact and experience. In the course of his ministerial service, he

was at one time sent as a missionary to one of the islands of the

West Indies, and there he saw it, and having human sympathies, felt

it. One illustration, which I had from his own lips, I will give. At

one of his stations among the members of his church was a young and

beautiful girl – if my recollection is not at fault, intelligent and

accomplished, too, whose character and sorrows deeply interested

him. Of her piety and good conduct, he seemed to have no doubt.

After the relation of minister and member had continued along enough

to inspire mutual confidence, she sought his counsel on the most

momentous question that can arise in human experience and action.

She was a slave. Although the pretext of color was obliterated, she

was subject to the will, the caprice of one who wore the garb of a

fellow man. This was enough to grind the intelligent and sensitive

soul, but this was not all. Her master was her father and her

grandfather. With the quick sense of purity and morality awakened by

Christian experience and feeling, how keen must have been the

emotions of wrong and shame that stung the young disciple, the

offspring of lust and incest. But there was a deeper depth of grief

and degradation for her. Whether from advances actually made, or

from the known character of her brutal master-father I know not, but

her soul was harrowed by the fear that he would compel her to submit

to his doubly incestuous lust, and her anxious and agonized and

repeated inquiry of her pastor was, whether it was not her duty to

commit suicide to preserve her chastity. And he confessed to me that

it was a question, too awful for him to decide. He could only weep

with her, and bid her trust in God and pray for deliverance.

I could add more from his West Indies experience to show the moral

horrors of slavery, but choose rather to give a characteristic

anecdote of him which may provoke a smile. His residence in Upper

Alton (Salu) was at a point where Smeltzer’s ferry road – leading

into Missouri – branched off from that which was traveled towards

northern Illinois. Of course, the immigrants into Missouri took

slaves with them, and it was easy to distinguish them from those

intending to settle in our State. One day a moving train came to

this point with the usual assortment of colors marking our western

neighbors, and either hesitated or were taking the wrong road. Mr.

Pinckard ran out and called to them, “Here, you must take the left

hand, you with the darkies,” and he added, “I am afraid you will

always have to take the left.” He was a good man, and when

afterwards I tried to sound the gospel trumpet, although of a

different denomination, his sympathies and his prayers helped me.

[The editor of the Telegraph added: Rev. Nathaniel Pinckard was the

father of William G. Pinckard, and came to Alton in 1818.]

Dr. Langworthy’s Christian name was Augustus. When I last heard from

him, he was living at Tiskilwa, Bureau County, Illinois. I find the

following in the Edwardsville Spectator, August 28, 1819:

'Post offices have been established at Alton, Gibraltar, and

Carlyle. Dr. Augustus Langworthy is appointed postmaster at the

former place, and Thomas F. Herbert, Esq., at the latter.'

I will add that Daniel D. Smith was appointed postmaster at

Gibraltar."

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO. 7

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: Alton Telegraph, October 14, 1864

"I hope Mr. Flagg, or whoever may be employed as the historiographer

of the Historical Society, has a good planning mill to winnow out

the few grains of wheat there may chance to be among the mass of

chaff in these rambling sketches, by the old-fashioned hand process

would hardly pay, but improvements are the order of the day, and who

knows, but some patent separator may soon, or already be discovered

by which all that is worth saving may be got out and put away by

steam?

Sometime in the winter of 1819-20, perhaps in February, a family

arrived in Milton which had a more important relation to myself than

to Madison County. And yet the State of Illinois and county of

Madison, and even the city of Alton have since felt its influence. I

had known Elijah Slater from my first coming to the State. Indeed,

we had met on the Ohio River, which we were descending at the same

time – he on a raft of lumber, which he had purchased at Olean, and

I in the cockle boat previously described. Both stopped a while at

St. Louis, and then came to Milton, where a friendship was formed

which was cemented by religious sympathies and efforts. After a few

months, he returned to his former home, Ithaca, New York, and in the

winter aforesaid, arrived in Milton with his family. It may amuse my

readers, especially the descendants of that good man, to see an

account of his reception in those primitive times.

I had become a widower with a child of some two years. Unwilling to

part with the little one, and indeed knowing no one to whom I could

entrust her, I prevailed on a kind friend, the daughter of the good

Deacon Crocker, at whose house in St. Clair County my wife died, to

come home with me and keep house. We were sitting one evening by a

bright cabin fire, when a knock was heard and Mr. Slater entered. He

informed me that he had brought his whole family along, and expected

them to tarry in Milton awhile until he could get a house built on

the farm he designed to make. “Well bring them in,” I said. “I don’t

know, but it will make too much trouble, and take too much room for

them all to come. I guess part of us, at least, had better go to Mr.

Seely’s.” Mr. William Seely had come to the West with Mr. Slater,

and afterwards settled on the Vermillion River. “Well, bring them in

for the present anyhow.” It was amusing to see the blank

astonishment and alarm in the countenance of Miss Crocker, when she

said to me after Mr. Slater went out. 'Why, what in the world are

you going to do with them?' 'Do with them? Give them a place to

stay,' I said. 'They have beds.'

In order to feel the force of her question, it may be necessary to

describe the mansion of which the hospitalities were thus offered.

It was a log cabin, say 16 by 18 feet, with a shanty closet perhaps

six feet square, and a loft above in which I could possibly stand

erect, under the ridge pale. Mr. Slater’s family, then with him,

consisted of himself and wife, and three daughters. And the driver

of the team must have a place, of course. I do not think his son,

Samuel, was with them then.

The result was that a part of the family took up their temporary

abode with us, and a part with Mr. Seely, until in early spring,

there were houses built for both families on farms which they opened

(or rather enclosed) on the prairie north of Sugar Creek, some six

miles from where Springfield was, a couple of years afterwards,

located by commissioners as the county seat of the newly erected

county of Sangamon, of which county seat they were among the very

first inhabitants. In inviting them all into my little cabin, I did

just as we were all accustomed to do in those days, and without any

apologies.

On my return from the trip to Sugar Creek mentioned in a previous

number, I was bringing my bride home. At Honey Point, where we

stayed all night, there were travelers already provided for, and I

and my wife slept on a buffalo robe, spread on the floor. There was

no other way.

The second of Mr. Slater’s daughters came with them a married woman.

Her husband, Mr. Joseph Torry, soon followed, and joined in the farm

enterprise. A few months afterwards, I was married to the eldest

daughter, and in the autumn, Mrs. Torry and my wife both died,

within a week of each other. Though not perhaps exactly within the

scope of my sketches, it may not be uninteresting to the present

generation of Madison County to add that the third daughter was a

year or two afterwards married to Dr. Gershom Jayne, to whom Alton

is indebted, in part, for what was deemed an important improvement,

and that their eldest daughter is the wife of the Hon. Lyman

Trumbull. As he and his family have somewhat been intimately

associated with the fortunes of Alton and the county, it seemed

proper to mention these facts.

Of Mr. Slater I have to say, that he was a man of more than ordinary

worth. Though somewhat visionary in business matters, he was in

other respects a man of sound sense and good information, a devoted

Christian and peculiarly amiable. And his wife was one whom to know

was to love. Their evening of life was rendered happy by filial love

and care in the pleasant home of their surviving daughter."

[EDITOR’S NOTE: The first wife of Thomas Lippincott was Patience

(Patty) Swift, a teacher, 7 years older than Thomas. She had lost

her parents at the age of 22 years, and took up teaching as a

livelihood. They had one daughter, Abia Swift Lippincott, who would

marry in 1834 to Winthrop Sargent Gilman, a friend of Elijah P.

Lovejoy and Captain Benjamin Godfrey. Thomas and Patty established

at Milton the first Sabbath School in the State of Illinois. After

one summer at Milton, Patty became so sick that Thomas became

alarmed. He would place her in a buggy and drive ten or twelve miles

a day into the country, away from the unhealthy, stagnant Wood

River. At first, she improved, but when they reached a friend’s

house in St. Clair County near Shiloh, she became very ill, and died

October 14, 1819, nine days after giving birth to a son, who did not

survive. She was buried in the old cemetery at Shiloh, but no

gravestone marks her resting place. Since then, the cemetery itself

was cut in two by a road to Belleville. Thomas married again on

March 25, 1820, to Henrietta Maria Slater, daughter of Elijah

Slater. She died September 1820 of the same malarial fever his

previous wife had died from. Lippincott then moved to Edwardsville

to get away from the unhealthy climate of Milton. He remarried again

on October 21, 1821 at Edwardsville, to Catherine Wyley Leggett,

daughter of Captain Abraham Leggett of Edwardsville.]

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO 8

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Number 8 was not found in the newspapers.

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO. 9

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: October 21, 1864

"My family suffered much with sickness while we resided in Milton.

The dam on the edge of the ledge of rocks across the Wood River,

just below the bridge, was supposed to create malaria. I know I have

often, of a summer evening, held my breath or my nose while passing

over the bridge. Dr. John Todd of Edwardsville was our physician.

But as he was ten miles off, and had a most extensive practice, we

had occasionally called in Dr. Clayton Tiffin, who resided at St.

Mary's, only three miles off. Perhaps my readers will wonder where

St. Mary's was, within that distance. A year or so afterwards, I was

called from Edwardsville to marry my friend, Ebenezer Huntington, to

the sister of Dr. Tiffin, the ceremony to be performed at his house

in St. Mary's. I went, and found a level plain at or near the mouth

of Wood River, on the lower side, with a two-story framed house on

it, in which Dr. Tiffin resided. That was St. Mary's. Whether the

town of Chippewa, of which I heard some years ago, occupied the same

spot, I do not know, but doubt whether it was as well built, if as

populous.

The town of Edwardsville was in those years an important place. It

was the residence of Ninian Edwards, who had been the only Governor

of the Territory of Illinois, and was now a Senator in the Congress

of the United States. Jesse B. Thomas, his colleague in the Senate,

was also a resident of Edwardsville, and the two distinguished

citizens, with their accomplished families, formed a nucleus round

which the intelligent naturally gathered. We know that the young

ladies shone as brilliant gems in the gay and polite circles of the

city of Washington.

These two men have filled places in the political history of not

only the State (as well as Territory) of Illinois, but of the United

States, too important and prominent to be soon forgotten. If this

were the place, or I the person, to give the political history of

the times and the actors in them, it would be easy to find many

materials, and pleasant to gather them. But, though I might collect

many facts of interest, there would be so many more left out for

want of documents and memory, that I shall not attempt it. Of Judge

Thomas I will only say that he was a man of gentlemanly and pleasant

manners, and without any remarkable powers of mind (of which he was

sensible) could and did exert a great influence over the people. It

was he who in 1820 presented to Congress the celebrated compromise

on slavery, by which Missouri was received into the Union. No one at

home supposed him the author, nor would they if they had not known

from the current reports of the day that it emanated from Henry

Clay. Fully convinced as I was, and am, of the good intentions of

the movers in this measure, it seemed to me an unfortunate attempt

to mingle iron and clay, wrong with right, and likely to prove

disastrous, only postponing and greatly aggravating the catastrophe.

With a number of others among us, I was, therefore, opposed to it.

Whether our judgment has been vindicated by the present rebellion

[Civil War], which cannot but be traced to that compromise as one of

its causes, may be left to the candid judgment of the present and

future generations.

Of Ninian Edwards I could find it in my heart to say much more.

Besides the fact that his abilities were superior – that he stood in

the councils of the Nation as a power, and filled, I may say, the

first place in the political history of Illinois - I might be

influenced by motives of personal friendship to fill a large space

with my reminiscences. But I forbear. His government of the

Territory, his subsequent election as one of the first chosen

Senators, his career there, his fearful conflict with W. H. Crawford

in which both parties may be said to have been destroyed, his

appointment as ambassador and resignation of it, and finally his

election of Governor of the State to succeed Edward Coles, are

matters of history and need not be dwelt upon in these sketches. I

cannot forbear, however, to mention one thing which was known to me

more fully perhaps than to the public of that day. It is that: When

he found it advisable on account of some of the unpleasant

consequences of his contest with Mr. Crawford to resign his foreign

mission, he had received a large sum – I think nine thousand dollars

– from the United States Treasury for his outfit, and had actually

expended it. There was no legal claim on him for it, and many

thought no moral obligation to repay it, for he had expended it in

the legitimate objects of, and as a necessary preparation for his

mission. He, however, from his private fortune, returned the money

into the treasury.

Few more genial, pleasant, and interesting men are to be found in

the walks of private life, few could attract more strongly in the

social circle than Ninian Edwards, and a vein of egotism always

discernable rather enhanced than diminished the zest of social

intercourse. Of Edwardsville and its men of that day, I may have

much to say in the future numbers."

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO. 10

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: Alton Telegraph, October 28, 1864

"The town of Edwardsville had been laid out before I was acquainted

with the county, and was the seat of justice. It occupied a ridge

jutting out from the Cahokia River, having on each side a somewhat

deep and abrupt ravine separating it from the level land adjacent.

Thus, it had but one street, or scarcely more, and in this respect,

as well as in its position, I believe is pretty much the same yet.

The court house was a log building on the edge, next to the street

of the square, which was a remarkably contracted opening not far

from the lower end of the town. The jail on the same piece of ground

was no more remarkable for beauty or strength. It was composed of

logs, and perhaps lined with plank. Nor could the brick court house

and jail built a few years afterwards be called a great improvement.

I remember when Lorenzo Dow came to Edwardsville and preached, some

years after this, when he was shown the court house as the place of

meeting, refused to preach in it, saying it was only fit for a hog

pen. It had not yet a floor, except a narrow staging for the court

and bar.

About this time (I mean 1819), some gentlemen purchased a farm at

the south – rather southeast end – and laid it out in blocks and

streets, with an open square of reasonable size in the center. It

was designed not only to rival, but supersede and swallow up the old

town, and probably to this end (for I can conceive no other) it was

laid out in such a way as not to connect by streets with the street

already established. While the form of the ridge controlled the

course of the main street, there was no reason, but the caprice of

the proprietors, why the streets of the addition should not

correspond with it, or else with the cardinal points of the compass.

But it agrees with neither, and moreover, the old street was made to

butt against a solid road at the junction.

The proprietor of the old town was James Mason, who had purchased it

before I knew it. He had built a brick house on the rear of the

square, in part of which an inn, or as it would now be called, a

hotel, was kept by William C. Wiggins, afterwards so well-known at

Wiggins Ferry, St. Louis. At this hotel might have been seen during

the years of its occupancy by Mr. Wiggins a number of men of no

small note – the elite of that day, both of our own citizens who had

not yet made homes, and especially of those who came to spy the land

with a view to future settlement. For comfort, for good living in a

plain way, such as was then thought genteel enough for the best, and

for neatness, the public house of Mr. Wiggins furnished a resting

place which the intelligent and refined traveler was well prepared

to appreciate, after a horseback ride across the State, over the new

roads, and stopping at the log farm houses on the way.

Edwardsville was at that time the most noted town, perhaps, in

Illinois. Though the old capital was at Kaskaskia, and the new

prospectively at Vandalia, neither was as much a point of attraction

as Edwardsville – not merely for the reason that as I said the chief

men of the young State resided there, but more, and perhaps mainly,

as the point, to which people came as a center from which they were

accustomed to go out prospecting. For I think the west side of the

State at that time invited immigration much more than the east. The

land district had been opened, and the land office established at

Edwardsville a few years, and consequently all who wished to settle

anywhere north of the Kaskaskia district must enter their land at

our county town. The lands were sold by the government on a credit

at two dollars (the minimum) per acre. On paying one-fourth of the

purchase money down, the remainder might be delayed. This was

doubtless in order to enable the settler to make the balance by

labor on the land; which was doubtless often done. But

unfortunately, the spirit of speculation was aroused. Thousands upon

thousands of acres were purchased by non-residents on more

speculation. And the actual settler was deluded with the hope of

making money to pay the balance, and so entered three or four times

as much as he had money to pay for. And, as if to excite speculation

still more, a person might by depositing sixteen dollars on a tract

(80 acres), one-tenth of the purchase money, secure a pre-emption

for a certain length of time, and then, if I do not forget, transfer

it to another tract, if he preferred it. Such was the state of

things at that time, and consequently, there were many congregated

at Mr. Wiggins’ house from time to time, and at all times, whose

object and business it was to enter many or large tracts of land, to

be kept until the price of land should rise. These were, of course,

men of property, and many of them men of intelligence and standing,

and added to the residents, made a lively and pleasant society."

EARLY DAYS IN MADISON COUNTY, NO. 11

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: Alton Telegraph, November 18, 1864

"At the establishment of the Land Office at Edwardsville, Mr. McKee

was appointed Register, and Benjamin Stephenson, Receiver. The

former died, and Edward Coles had been appointed his successor

before I became acquainted there. It was the wish of the friends

that William Paton McKee, a son of the deceased, who had in fact

conducted the office from the beginning, should be appointed to the

place, and interest was made for him, but he was a minor, and the

Government declined. As the next best thing, it was understood that

one should be appointed to hold it until young McKee came of age.

The estimation in which he was held may be inferred from this, and I

will only add that this estimation was general, and that it

continued to the end of his life. A close and intimate acquaintance

with his private, as well as his official character, enables me to

say that he was in all respects worthy of the very high regard which

all entertained for him.

Of Colonel Stephenson, I have to say that he was a plain, unassuming

man, not highly educated, but of practical, good sense, and amiable

and pleasant in the circles of social life. His position, and

especially the elegant and high-toned manners of his beautiful and

attractive wife and daughter, the latter just budding into

womanhood, together with their close association with the

accomplished family of Governor Edwards, placed him and his among

those who were at the head of society, alongside of the family of

Judge Thomas, whose step-daughter, Miss Rebecca Hamtramck, shone as

a brilliant star in the fashionable circles of Washington city.

Indeed, we had evidence that Edwardsville, in the persons of Miss

Julia Edwards, afterwards Mrs. Daniel P. Cook, as heretofore

intimated, and Miss Hamtramck furnished society in the National

Capital with some of the most perfect specimens, in one case of

charming, modest beauty, and grace, and in the other, of dashing,

elegant manner and splendid appearance, that it could boast during a

session of Congress, within the Presidential term of John Quincy

Adams. With these, and others fully competent to associate with

them, and the stranger heretofore mentioned, it may not be too much

to say that there was an intelligent and refined, if not a

fashionable society in Edwardsville, as early as 1819 and 1820.

There were three brothers in Edwardsville at this time, and for some

years afterwards, who occupied conspicuous positions, though not

much in the official line. James, Paris, and Hail Mason. The first

of these, James Mason, was as I have said, proprietor of the old

town plot [Edwardsville]. He was a genial, pleasant man, seeking

mainly the acquisition of wealth, and having no political ambition.

His home and family were ever a place of delightful resort, not only

from his own cheerful, good fellowship, but especially rendered so

by the cordial, sprightly, and lady-like manners and interesting

conversation of his wife. Paris Mason was an industrious man, and

carried on a mill at the foot of the street, where the Cahokia was

dammed for that purpose. The third, Hail Mason, was for a number of

years a Justice of the Peace, and a useful, worthy citizen, well

known and enjoying the confidence of all. He afterwards became

_______ in the Methodist connection for a few years. But they all

died years ago.

The first Register of the Land office at Edwardsville was John

McKee. His son, who was deputy or chief clerk under his father in

the register’s office, held the same place under Edward Coles, who

was appointed to fill the vacancy occasioned by the death of John

McKee. The son’s name was William Patton McKee. “He resigned when

McKee became of age.” I do not know when Mr. McKee came of age, nor

the exact time when Mr. Coles resigned the office of Register, but I

presume he resigned previous to his inauguration as Governor of

Illinois, which took place December 5, 1822. Colonel Benjamin

Stephenson, Receiver of Public Moneys, died on October 16, 1822. His

death caused the postponement of the Land Sales, which, by the

President’s proclamation, were appointed to be held about that time

at Edwardsville. In giving his readers notice of this postponement,

the editor of the Edwardsville Spectator assigned two causes for it,

to wit:

1st, the death of the Receiver, and 2nd, the absence of the Register

– Mr. Coles having taken the liberty, between his election and

inauguration, of visiting his aged mother in Virginia. Mr. McKee

tried to convince the editor that the absence of Mr. Coles had