Early History of Illinois

The following eight articles were written by "An Old Resident," and published in the Alton Telegraph in 1848. These articles detail the first pioneers who were brave enough to venture into the Illinois Country, where they faced many hardships, including attacks from the Indigenous people.

___________________

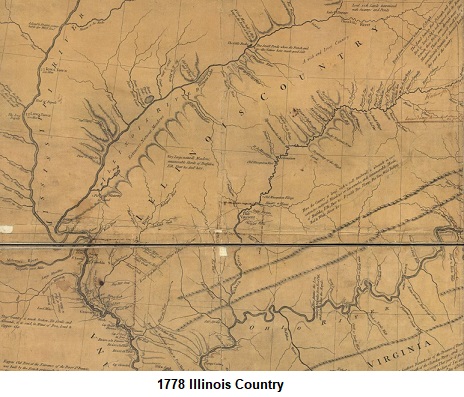

HISTORICAL TIMELINE:

In 1778, General George Rogers Clark defeated the British at

Kaskaskia, securing the Illinois Country for Virginia.

In 1783, the Treaty of Paris extended the U. S. boundary to include

the Illinois Country.

In 1784, Virginia relinquished its claim to Illinois.

In 1787, the Northwest Ordinance placed Illinois in the Northwest

Territory, with Arthur St. Clair as the Governor.

On July 04, 1800, Congress created Indiana Territory, which included

Illinois.

In 1803, the United States purchased approximately 872,000 square

miles west of the Mississippi River (called Louisiana) from the

French.

On May 14, 1804, William Clark and his troops departed from Camp

Dubois (at the mouth of the Wood River), in future Madison County,

to join Meriwether Lewis for their westward explorations.

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS, NO. 1

By an Old Resident

Source: Alton Telegraph, April 07, 1848

In a few continuous numbers, we propose to place before the readers

of the Illinois Journal, as being the oldest newspaper in the State,

some sketches, historical and biographical, of the pioneers of

Illinois. We allude, particularly, to those of American origin – of

the Anglo-Saxon stock – for, in a historical sense, the French were

the first to enter and form settlements near the Illinois and

Mississippi Rivers. Our plan does not propose a complete, or even a

consecutive series of the scenes through which they passed, but only

sketches or gleanings, as may come in hand. The amount we may glean,

and the particularity of our sketches, will depend on our leisure

and other circumstances. The period through which we propose to

range is comprehended in what may be denominated the “Territorial

History of Illinois from 1780."

At the period to which I allude, with the exception of the French

villages of Cahokia and Prairie du Pont in St. Clair County; and

Kaskaskia, Fort Chartres, Prairie du Rocher; and Village a Cote in

Randolph County; the whole State was the hunting grounds of the

savages. There were, however, half a dozen French families on the

Wabash, opposite Vincennes, and trading posts at Peoria and one or

two other places where were to be found a few Frenchmen or half

breeds, with their Indian wives. The Indians were by no means as

numerous as the fertile imagination of some have made them. At the

commencement of the eighteenth century, their whole number, as

counted up by the Catholic Missionaries who visited and officiated

in all their villages, did not amount to five thousand. A few

hunters and an occasional trader visited Kaskaskia before Clark made

his formidable appearance, took possession of the place, and

literally scared its panic; struck inhabitants into submission and a

firm and perpetual friendship.

The first Americans that came to the country were from

Shadrach Bond Sr., as customarily distinguished – Judge Bond – was a

native of Maryland, near Baltimore, but subsequently removed to

Virginia. He was an uncle of the late governor Bond, who bore his

first name. He was a man of respectable talents, of sound judgment,

great firmness, excellent moral character, and took a leading part

in the first religious meetings held by the early pioneers, by

reading printed sermons and portions of the Scriptures on the Lord’s

day. These meetings were frequently held at his house, which was in

the American Bottoms, and near the present road from Waterloo, by

Columbia, to St. Louis. In the Indian War that followed, it was made

a “station,” and known as the “Blockhouse Fort.”

Another colony of Americans arrived from Western Virginia in 1785.

Amongst these were Captain Joseph Ogle, James Worley, James Andrews,

and several other families. Captain Ogle, as he was always called,

many of whose descendants now live in St. Clair County, deserves

especial notice. He originated from the south branch of the Potomac,

and was amongst the Zanes and others in the first attempt to settle

the country in the vicinity of Wheeling. Withers, the historian of

Western Virginia, says, “In 1769, Colonel Ebenezer Zane, his

brothers Silas and Jonathan, with some others, from the south branch

of the Potomac, visited the Ohio for the purpose of making

improvements, and severally proceeded to select positions for their

future residences.” Captain Ogle was already trained in Indian

warfare, and probably he and his brother, Jacob, who was killed at

the siege of Fort Henry in 1777, were amongst the “others,” who

accompanied the Zanes.

Fort Henry was situated one-fourth of a mile above Wheeling Creek,

the garrison numbered 42 fighting persons, old and young. The

storehouse was well supplied with muskets, but sadly deficient in

ammunition. In the month of September 1777, about 400 Indians,

headed by the notorious S___ Girty, were found concealed in a

cornfield, and Captain Mason, with 14 men, was sent out to dislodge

them. Their numbers were then unknown, for only a dozen or more had

shown themselves. These made a retrograde movement towards the

creek, where the main party lay in ambuscade, until Mason and his

small party were surrounded, and assailed in front, flank, and rear.

The Captain rallied his men, attacked the Indians, and broke through

their lines, but in the desperate conflict, more than half the men

were killed, and their leader, severely wounded, concealed himself,

with two of his men, in the fallen timber, who were all that

survived. Soon as their critical situation was known in the fort, by

the firing of the Indians, Captain Ogle, with 12 men, went to his

rescue. This devoted band, eager to relieve their companions, fell

into the ambuscade, and more than half were slain. Three other

volunteers left the fort to aid Ogle and his party, and his brother,

Jacob Ogle, was mortally wounded, and Captain Ogle and the surviving

men had to seek shelter in the woods. Captain Ogle, in running

through the cornfield, had several Indians in close and eager

pursuit, who were but a few yards behind him. The fence over which

he had to pass was ten rails high, and as not a moment’s time could

be spared in this emergency, he arranged, while running, to strike

his foot on the fourth rail, and by a tremendous effort, pass over.

In this he was entirely successful, but was so much exhausted that

he fell on the outside, and crawled into the weeds under the fence.

In a moment, two Indians mounted the fence and sat on the adjacent

panel, their dark eyes peeling into the brush and timber beyond. He

retained his rifle, and it was loaded, his finger was on the

trigger, and his eyes fixed on his enemies, watching their motions,

determining, should he be discovered, to shoot one and rush on the

other with his knife. After several minutes, the Indians appeared to

relinquish the pursuit, returned to their party, and the fearless

Captain made his escape.

The fort now contained but 13 men and boys, with a large number of

women and children, when it was invested by Girty with his savage

army. Colonel Shepherd, who commanded, received a challenge from

Girty to surrender, and replied, “Not while a man of boy lives to

defend it.” The Indians attacked the fort with their whole force –

the females loaded the rifles, while the men and boys took deadly

aim at the assailants. Their store of powder soon became nearly

exhausted, but a keg was at the house of Colonel Zane, about sixty

yards from the gate of the fort, but what man or boy would hazard

his life to obtain it? At this crisis, in which the fate of the

whole garrison depended, Elizabeth Zane, a young lady, just returned

from school in Philadelphia, volunteered to obtain the supply. The

Indians offered no molestation as she went out, but as she returned

with the keg in her arms, they suspected her errand, and poured at

her a shower of balls. But in the wonderful Providence of God, she

escaped unhurt. The attack continued throughout the day, that night,

and the next day, when reinforcements, raised by Captain Ogle, came

to their relief, and drove off the savages.

Captain Ogle was a man of unblemished morals, of uncommon firmness,

and self-possession of which his watching the Indians while lying

under the fence is an illustration. He was a great friend to liberty

and human rights. He brought his slaves from Virginia and set them

free in Illinois. Their descendants are industrious, worthy people,

and own and cultivate farms in the northern part of St. Clair

County. He was benevolent, humane, and exhibited great moral

firmness and decision of character. He had no education from books,

and could not read or write, and yet his mind, by self-culture, was

well disciplined. He was well qualified, and hence naturally became

the leader and counsellor of the people in the settlement where he

resided. Mild, peaceable, and kind-hearted in social intercourse,

always striving for the promotion of peace and good order in

society, yet terribly combative in defense of the frontiers from the

tomahawk of the ruthless savage. What the poet says of the

fictitious Rolla, may be applied with much pertinence to Captain

Ogle: “In war, a tiger chafed by the hunter’s spear. In peace, more

gentle than the unweaned lamb.”

He was strict in the fulfillment of all his engagements, and

expected from all his neighbors the same honesty and punctuality. He

professed to be converted to God under the preaching of Elder James

Smith, who made his first visit to Illinois in 1778, and

subsequently joined the Methodists, being the first person to put

his name to the Class paper in 1793. He had two wives in successive

periods, both members of the Methodist Episcopal Church, as are many

of his numerous descendants. He had three sons – Benjamin, Joseph,

and Jacob – and several daughters. One daughter was the wife of the

late Charles R. Matheny, Esq., of Springfield. Captain Ogle died,

honored and beloved by all his acquaintances, in the northern part

of St. Clair County (where he had resided from 1802), February 24,

1821, at the age of more than fourscore years. His three sons have

all died within two years.

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS, NO. 2

By an Old Resident

Source: Alton Telegraph, April 14, 1848

Amongst the colonists who accompanied Captain Ogle, we mentioned

James Worley. His history is told in a few words. Of his early life,

we now nothing. In 1796, a party of Osage Indians came over the

Mississippi on a marauding enterprise, stole some horses, and were

pursued by the Americans. Mr. Worley got in advance of the party,

was shot, killed, scalped, and his head cut off and left on the sand

bar in the river where the Indians re-crossed.

In the summer of 1787, the little settlement was strengthened by the

arrival of James Lemen (whose wife was the daughter of Captain

Ogle), George Acheson, David Waddel, William Biggs, and several

other families. The same year the Indian hostilities commenced, and

continued for nearly ten years, with intervals of apparent

quietness. During this period, the Indians were hostile throughout

the frontier settlements of the northwest, and along the lake

country to the State of Pennsylvania.

The American settlers in Illinois began to erect blockhouses of

“stations,” as they were called, for defense in 1788, where

occasionally, for a whole season, a number of families lived in a

sort of community form for mutual protection. A number of cabins,

equal to one for each family in the community, were erected, usually

on two sides of a square or area, which made a large yard in common.

The doors and apertures of the cabins opened into the yard. A second

story of logs was laid over the first, especially on those cabins

placed at the corners of the enclosure – the logs projecting over a

few inches so as to afford convenient opportunity to shoot obliquely

downward at the assailants. The spaces around the yard were fitted

up with palisades – these were logs, a foot or more in diameter, and

twelve or fifteen in length, planted firmly in the ground and

closely joined together. The gate for the common pass way was

usually made of thick slabs, split from large trees, and hung with

stout, wooden hinges. In time of alarm, the few cattle and horses

owned by the people were brought within the enclosure. With a supply

of water and plenty of provisions, rifles and ammunition, a corps of

resolute white men would beat off five times their number of

Indians. In only a very few instances were such “stations” overcome

by an Indian army.

The Indian method of besieging a fort is peculiar. They are seldom

seen in any considerable numbers. They lie concealed in the woods,

bushes or weeds, and toward autumn, in the cornfields adjacent, or

behind stumps and trees, they waylay the path or the field, and cut

off individuals in a stealthy manner. They will crawl on the ground,

imitate the noise and appearance of swine, bears, or any other

animal in the dark. Occasionally, as if to produce a panic and throw

the besieged off their guard, they will rush forward to the

palisades or walls or gateway, with fearful audacity, yelling

frightfully, and even attempt to set fire to the buildings, or beat

down the gate. Sometimes they will make a furious attack on one

side, as a feint to draw out the garrison, and then suddenly assail

the opposite side. More frequently, if they have a strong party, the

main body lies in ambuscade, while a small number show themselves,

as was the case at Fort Henry, as noticed in our first number.

Indians are by no means brave. Naturally they are cowards,

especially those of the Algenuin(?) race, which included all those

tribes which assailed the settlements in the northwest.

In 1788, the war assumed a more threatening aspect in Illinois. The

principal cause of this series of Indian wars, after peace with

Great Britain, will be given in a future number.

James Lemen was quite independent in his feelings and judgment,

rigidly honest, and a humane, benevolent man. He was determined,

very conscientious, very firm, but never quarrelsome or vindictive.

In principle, he was opposed to war, and yet when compelled from a

sense of duty, arising from necessity, as was the case when the

Indians assailed the settlements, he would fight like a hero in

their defense. Early in the Spring of 1780, he fitted out a

flatboat, near Wheeling, to transport his family and moveables down

the Ohio River. On the second night, the river fell, and his boat

lodged on a stump, careened and sunk, by which casualty he lost all

his provisions and furniture. Though left destitute, Mr. Lemen was

not the man to become disheartened. He persevered, got down the Ohio

River, and up the Mississippi to Kaskaskia, where he arrived on July

10. He eventually settled at New Design. He was an industrious man,

strictly honest, and devoutly pious from early youth, but did not

make a public profession of religion until some years after his

arrival in Illinois. Himself, his wife, and two others were the

first persons ever baptized in Illinois, which took place in

February 1794. They raised a family of six sons and two daughters,

all of whom have had large families, and their descendants are quite

numerous in the southern counties in this State. A large proportion

who have come to years of understanding, are members of Baptist

Churches. Four of his sons have been ministers of the gospel from

early life, as their father was from about the age of fifty years.

His third son, James Lemen, was a member of the Territorial

Legislature, a delegate to the Convention that formed the first

constitution, and subsequently, for several years, a member of the

State Senate. Robert, the eldest son, was for many years U. S.

Marshal, first of the Territory, and then of the State. James Lemen,

the father, was a man of method and system, an enterprising farmer,

at one period a Judge of the County Court, under Territorial

jurisdiction, and in various ways an influential and useful citizen.

He died of the winter fever, after a few days’ illness, surrounded

by all his children, in December 1823, in the calmness and fortitude

of the Christian hero. His venerable widow survived until 1840.

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS, NO. 3

By an Old Resident

Source: Alton Telegraph, April 21, 1848

[Note: This article was extremely hard to read, resulting in blanks

and possible errors.]

A very common notion has been entertained in the “old thirteen

States,” and more especially New England, that the pioneers of the

West were a rough, half-civilized class; ignorant, indolent, and

altogether unfit to constitute the _____ of virtuous society. Proofs

of this in the minds of strangers are drawn, as the schoolboy says,

a _____. Here are the reasons. They lived _____ hunting, fought

Indians, were hunting-_____, shirts, moccasins and skin caps –

envied a ____ with a belt, powder huru, butcher-knife, and tomahawk,

by their side, when _____ading the forests or prairies – lived in

log cabins – eat their homely and often scanty meals from platters

or wooden trenchers, pound their corn in a handmill, or pounded it

in a mortar, and drank their milk from a tin cup. They were an

uncivilized, un-Christianized, barbarous, fighting, flory-_____,

whisky-drinking race, who ought to have been prevented from making

Territorial and State Governments “by law,” - they were squatters,

who settled on the public lands, that specially belonged to the old

“thirteen States,” and got preemption rights, thereby depriving

enterprising and respectable land jobbers of the privileges of

monopoly. These pioneers were very unreasonable for not living in

densely populated districts, and being satisfied with the

guardianship of their betters, who were _______ to form the social

compact, and make laws for their Government.

Such have been the reasonings of thousands, both statesmen and

Christians. By the same mode of drawing inferences, we, ____ the

West, can prove to a demonstration, that the pioneers of New England

were ____ a backwoods race. They lived on _____ hunted game, wore an

uncomely dress, showed a sun-browned, weather-beaten, ______;

domiciled in log houses, killed Indians, and what is more to the

_______, organized Governments, like Western Pioneers, and made

their own laws, or, as ________ historian, Hugh Peters

affectionately “adopted the laws of God until they did get time to

make better.” There are _____ direct, that the pioneer puritans were

very uncivil people, and wholly unfit to _______ settlements in a

new country. They ought to have stayed at home, minded their

betters, and waited until the country became populous, intelligent,

and ______.

Last summer, a venerable clergyman ____ “down cast” – came to

Chicago to ___ the great internal improvement Convention. He had

gotten, as he supposed, to “””” renowned place, ______ the Far West.

He opened his eyes with a wide stare, raised his hands towards

heaven in astonishment, and prepared a written speech, expressive of

his amazement that the people were civilized – for they looked

almost like Christians, and read a prosy speech to show that all

this wonder of wonders was produced by the peculiarities of New

England puritanism. He was replied to by Senator Corwin of Ohio, in

a witty, amusing and satirical style, which proved a “knock-down”

argument to the old gentleman’s fancies. This story illustrates the

propensity uncommon, to judge that people at a distance, and of whom

we have no particular knowledge, are of course so vastly out

inferior in knowledge, common sense, and virtue.

We have already described the “stations” the people had to erect for

their safety, and their constant exposure to Indian assaults. From

1786 to 1795, an Indian War prevailed through the frontiers of the

northwestern territory, and the settler in Illinois were sufferers

to no small extent. We are aware there are fixed impressions in the

minds of many humane, benevolent persons, whose notions of Indian

character have originated, or been strengthened, by occasional

speeches in Congress, made not exactly for “Banklim,”(?) but for the

special benefit of party, by newspaper editorials and fancy sketches

– that Indian assaults originate in the mal-administration of the

national Government or the culpidity of the whites in their invasion

of Indian lands. Nothing is further from the facts of history. Much

that has been written in favor of Indian humanity, fidelity, and

“attachment to the graves of their fathers,” is poetry. Nearly every

tribe of the Algonquin race have been a roaming, marauding people,

delighting in war and eager for

These facts are a sample of what may be found in exploring the

history of other Indian tribes. A large portion of the notions

entertained about Indians and their wrongs, by numerous persons in

the northern States, are wholly fictitious. We have no patience in

listening to the sickly sentimentality of those who throw the blame

of the border wars upon the national government or the hardy

pioneers, who they fancy are obtruders on Indian rights, and thus

sympathize with the “poor Indians.” And let it be understood, the

writer is a warm and consistent advocate for sending the blessings

of the gospel, and of civilization to the “red skins,” not because

he is an honest, inoffensive being, but because he is ferociously

wicked, deceitful, and cruel, because he delights in war, and

because in each marauding enterprise he commits depredations for the

love of fighting, and an insatiate desire of plunder. And he has

been a steady advocate for the removal of the Indians from within

the boundaries of organized States and Territories ever since the

humans and truly national plan was laid in the cabinet of President

Monroe, and received the hearty cooperation of the Great Patriot,

whose recent death the nation mourns.

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS, NO. 4

By an Old Resident

Source: Alton Telegraph, April 28, 1848

Amongst the individuals and families who were sufferers by the

depredations of the Indians at the period of these “incidents,” were

the names of Andrews, Smith, Biggs, and McMahon.

James Andrews came to the Illinois Country in 1785, in company with

Captain Joseph Ogle and others. The next year, his cabin was

assailed by a party of Indians – himself, wife, and daughter, killed

and scalped, and two other daughters taken prisoners and carried to

the Kickapoo towns on the Wabash. One of the girls was lost sight of

amongst the Indians, and it was never known whether she lived or

died. The other was ransomed by some French traders and restored to

her friends. She is still living, the aged mother of a large family,

within three miles of the writer.

James Smith was a Baptist minister from Kentucky, who visited the

settlement of New Design the first time in 1788, and spent some

weeks in preaching the gospel to the destitute population. He was

the first preacher (in distinction from Roman Catholic priests) who

officiated as a minister on the prairies of Illinois. Previous to

this, and subsequently to, the people were accustomed to meet at

each other’s cabins on the Sabbath, sing hymns and read a sermon of

portions of the Scriptures. A revival of religion followed the

preaching of Smith, and a number professed to be converted, but no

church was organized. On his second visit to Illinois in 1790, he

was taken prisoner by the Indians. He had been preaching in the

settlement, and transacting business for several days, and a number

of persons were seriously disposed – amongst whom was a Mrs. Huff.

On May 19, in company with this lady and a Frenchman from Cahokia,

he was riding from

William Biggs, with his family, came to Illinois from the vicinity

of Wheeling, Virginia in 1785. On March 28, 1788, in company with a

young man by the name of John Vallis, he was going from

Bellefontaine to Cahokia, when they were attacked by sixteen

Indians. The horse he rode was shot in several places, reared,

plunged, and threw him off the saddle. He attempted to run, but

became entangled in his overcoat and shot pouch, was overtaken and

made prisoner. Vallis was shot in his thigh, but being on a large,

fine horse, made his escape and reached the settlement, but he died

of the wound about six weeks after. The Indians took Biggs to their

towns on the Wabash, treated him kindly, and proposed to adopt him

into the tribe in place of a brave who had been killed. He was a

portly, fine-looking man, and a young squaw, who was a handsome,

neat widow, manifested strong and persevering desires to adopt him

as her husband. She was a daughter of the principal Chief, and her

style of courtship was modest and decorous according to approved

Indian fashion. She combed and braided his long hair into a cue,

cooked his breakfast, and brought it to the door of his camp at an

early hour, followed from village to village, endured with

high-souled feeling and patience the jeers of her Indian relatives

for her devoted attachment, and deemed the excuse of Biggs for not

complying with her matrimonial proposals a very silly one - that he

had a wife and three children in Illinois. At the Kickapoo village

he met with Nicholas Koniz, a young German about nineteen years of

age, who had learned their language and acted as a sort of

interpreter. Koniz afterwards obtained his release, went to

Missouri, and settled ten miles west of St. Charles on the Old

Boon’s Lick Road, where he kept a house of entertainment until his

death. Mr. Biggs also became acquainted with a British trader by the

name of McCausland, through whose kindness, and that of some French

traders at Vincennes, he negotiated his ransom for $200, including

his expenses, for which he gave his note payable in twelve months in

the Illinois country. He returned home by the way of Vincennes and

the Wabash and Ohio Rivers, after an absence of nine weeks.

Subsequently, Mr. Biggs became a resident of St. Clair County, four

miles northeast from Belleville, was a member of the Territorial

Legislature, a Judge of the County Court, and lived and died in the

confidence and respect of the community. In 1826, he published a

narrative of his captivity, visited Washington City, and obtained

the amount paid for his ransom and expenses, to which he was justly

entitled from the Government.

The Indians rarely came into the settlements in the winter months –

their usual custom leads them to commit depredations in the Spring

and Autumn, though it was not safe to be exposed at any period

during the Summer. At times, for many months, or nearly a year, no

Indians would be seen, and then the first notice would be the death

of an individual or the massacre of a family. One of the most

afflictive instances was the murder of the family of Mr. McMahon in

1795. No depredations had been committed for many months, and the

impression prevailed that the war was over. People began to leave

the “stations,” and improve their own land. Mr. McMahon had built a

cabin, and made a little improvement in what is now called “Yankee

Prairie,” about four miles southeast from Waterloo, in Monroe

County. This location was nearly two miles from that of James Lemen

Sr., his nearest neighbor. Towards night, seven Indians were seen

coming up a ravine from an adjacent thicket, and approaching his

cabin. Mr. McMahon saw them, and justly suspected their intentions

were hostile. He had a large blunderbuss [short-barreled,

large-bored gun with a flared muzzle, used at short range], loaded

with twenty small rifle balls, and had he fired on them and barred

the door, he might have saved his family. Unfortunately, his wife,

being frightened, caught his arm and would not let him fire. The

Indians entered the cabin in a friendly manner, shook hands with the

family, and immediately caught and tied Mr. McMahon so that he could

make no resistance. His wife ran, but they shot and dispatched her

and four of the children with the tomahawk. An infant slept in the

cradle, which they did not discover, but as it was the second day

after the massacre before the people found it, the little one was

dead. The Indians decamped with Mr. McMahon and one little daughte4r

prisoners, and took their customary course northeast through the

prairie and points of timber, leaving the Kaskaskia River on the

right. The first night, they securely tied the afflicted father, but

the second night he made his escape, leaving his little daughter,

and started homeward. For one day he lost his course, but reached

the settlement in safety, just as his neighbors were burying his

murdered wife and children. He calmly gazed on their mutilated

remains in the rude coffins in which they were about being enclosed,

as he came in sight, and with pious resignation repeated the words

of Scripture, “They were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and in

their death, they were not divided.” His daughter was subsequently

restored to her friends, grew up, married a Mr. Gaskill, and became

the mother of a large family in Madison County.

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS, NO. 5

By an Old Resident

Source: Alton Telegraph, May 05, 1848

It is necessary here to inquire into the circumstances of the

country and the national government, and the policy pursued toward

the Indians of the northwest, that the causes of the border

depredations already narrated may be understood.

At the commencement of the American settlements in the Illinois

country, it was almost literally without an organized government.

Originally, Illinois constituted a portion of Louisiana, and its

civil organization and laws originated from that source. The war

between England and Spain on the one part, and France on the other,

from 1754 to 1782, produced great and essential changes on the

continent of North American, and no less in the Illinois country.

France at that period was under the curse of a traitorous and

licentious monarch in the person of Louis XI, through whose

profligacy and that of his mistresses and minions, the nation lost

its possessions in North American. By a secret treaty at Paris

(1762), the King gave Spain all Louisiana west of the Mississippi

River, together with New Orleans and the country south of the

Ibbeville pass; and by the treaty with Great Britain of 1763, all

Canada and the Illinois country were ceded to the latter power. How

much British and Spanish gold was received to support the King and

his minions in their profligacy, the nation never knew. British

power was not exercised over Illinois until 1765, when Captain

Sterling, in the name and by the authority of the British crown,

established the provincial government at Fort Chartres.

In 1766, the “Quebec Bill,” as it was called, passed the British

parliament, which placed Illinois and the northwestern territory

under the local administration of Canada. The conquest of the

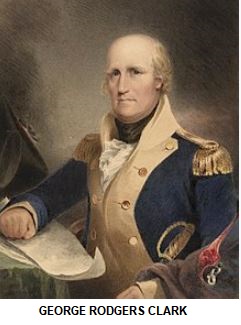

country in 1778, by Colonel C. R. Clark, brought it under the

jurisdiction of Virginia, and in the month of December of the same

year, an act was passed by the House of Burgesses of that State,

organizing the county of Illinois, and providing for the

administration of government under the authority of a Lieutenant

Governor, who was also commandant. During each of these changes, the

French laws and customs remained in operation.

Virginia, at an early period (1779) had by law discouraged all

settlements made by her citizens in the territory northwest of the

Ohio River. This has been the footing, and in many instances, the

legislative policy of the old States. The Great West has grown up,

not so much by the fostering policy of the old States, as by the

restless enterprise of the pioneers. The spirit of adventure and

migration has ever been stronger than arbitrary laws. For several

years, the position of things in relation to the protection of

government was precarious in the northwest. The territory was

claimed under the ill-defined boundaries of royal charters, by

Massachusetts, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. But the

latter State had the additional claims of conquest and possession.

These and other difficulties were adjusted by each State

transferring the right of sovereignty and title to the wild lands

(after some reservations), to the national confederation. The

cosstoir(?) of Virginia to the Continental Congress was made in

1781, but it was not till July 1787 the “Ordinance” was passed which

provided for a territorial government northwest of the Ohio River.

But the governor and judges were not appointed until 1788, and the

government was organized at Mariota in the month of July of that

year. Still, the Illinois country remained without an organized

government till March 1790, when Governor St. Clair and Winthrop

Sergeant, Secretary, arrived at Kaskaskia and organized the county

of St. Clair. Hence, for at least six years, there was no executive,

legislative, or judicial authority in the country. The people were

“a law unto themselves.” There was in reality no authority to which

they could apply for protection from Indian assaults.

The war with Great Britain, in which many of the northwestern

Indians were employed as allies, ceased by the adoption of the

provisional articles of peace at Paris, on November 30, 1782, and

all hostilities with the mother country ceased in January following.

The definitive treaty was made in September 1783. But a cessation of

hostilities with Great Britain was not necessarily a cessation of

hostilities with the Indian tribes. And while it was hoped the

border wars were at an end, none could foresee the result.

Soon, an unhappy controversy arose between Great Britain and the

United States, about carrying out certain provisions of the treaty.

Article 4 provided, “That creditors on either side should meet with

no lawful impediment to the recovery in full value, in sterling

money of all bonafide debts heretofore contracted.” The Continental

Congress had no power to compel the States to observe this or any

other article. Congress further agreed “to recommend to each of the

States to restore to the original owners all the rights, properties,

and claims, that had been confiscated, belonging heretofore to real

British subjects.” And “His Britannic Majesty shall with all

convenient speed, and without causing any destruction, or carrying

away any negroes or other property of the American inhabitants,

withdraw all his armies, garrisons and fleets, from the said United

States, and from every port, place and harbor, within the same,

leaving in all the fortifications the American artillery that may be

therein.”

These articles were violated by both parties. Some of the States

made ex post facto laws, virtually debarring the collection of debts

in sterling money, and though Congress recommended it, the States

refused to restore confiscated property. The British government, in

the spirit of recitation, refused to pay for negro slaves carried

off, and remained possession of the military posts of Oswego,

Niagara, Presque Isle, Sandusky, Detroit, Michillmackluae, and

Prairie du Chleq. Those posts were places of resort for the British

traders. Through their agency, the Indians of the northwest obtained

their supplies, and to these traders they sold their furs. There is

no documentary evidence that the British government countenanced and

encouraged the Indians in their hostilities to the Americans, but

there is abundant evidence that the traders, who were British

subjects, did. The traders were not benefited directly by the border

wars that followed, but the state of hostilities kept off all

Americans as competitors in the Indian trade, and furnished a market

to the British traders for supplies of munitions of war, clothing,

and other articles.

He celebrated and much abused treaty of the Hon. John Jay, concluded

in November 1784, and ratified by the President of Senate of the

United States in August 1795, adjusted the _____ in controversy with

Great Britain, and produced the cession of the military posts to the

northwest, and with the treaty with the Indians at Greenville, Ohio,

the same summer, put an end to the long series of Indian wars, and

opened the period of prosperity and growth to the northwestern

territory. Jay’s treaty did not obtain all that was claimed by the

United States, but it obtained all that could then be secured. No

one but a grave man, or a political desperado, devoid of every spark

of real patriotism, would have advocated a war with Great Britain at

that period, under the depressed circumstances in which the nation

was placed. And yet, for political purposes, and to break down the

administration of Washington, this treaty was opposed with great

vehemence and violence, especially in the House of Representatives,

where supplies were voted to carry it into effect. The interests of

the south were thought to be neglected. It became the watchword for

a political party then attempting an organization, and political

aspirants then were the same selfish, intriguing demagogues, and

could make the “worse seem the better reason,” as at this day. The

treaty went into effect only through the influence and unbounded

popularity of Washington, and proved in the issue a great benefit to

the whole northwest.

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS, NO. 6

By an Old Resident

Source: Alton Telegraph, May 12, 1848

Is the question asked, “Why did not the national government protect

the people of the Illinois Country and other portions of the

northwestern territory from the marauding savages?” The answer is,

it was wholly deficient in means, and until the adoption of the

Constitution in 1780, it was impotent in authority. The Continental

Congress could not levy a dollar, nor even provide troops, except by

the action of each State. Speele currency was hardly to be found in

the country; the people were impoverished by the seven years

struggle and privations of the Revolutionary War, and even after the

adoption of the Constitution in which ample provision was made for

national authority, the government was deficient in means. The

policy pursued towards the Indians was a wretched one. It was a

peace policy when the tribes were induced and disposed to be

hostile.

The national government was, through its commissioners, in the

attitude of

His second plan was to form “treaties of peace with them, in which

their rights and limits should be explicitly defined, and the

treaties observed on the part of the United States with the most

right justice, by punishing the whites who should violate the same.”

This certainly seems a humane paltry, and it was attempted to be

carried out to its full extent. Commissioners were sent to the

Indian tribes, councils were held, the “poor Indians” were reasoned

with, and advised and implored to be at peace with the United

States, and with each other. Treaties were actually made, and

wantonly violated on the part of the Indians before the ink was

hardly dry. Presents were liberally made, and they were instructed

how good and clever it was to live in peace with their neighbors,

and the war continued; families were butchered, and thieving and

marauding expeditions carried into long-established white

settlements.

The policy in the end proved not less ruinous to the Indians than it

did to the frontier white settlements. This policy impressed them

with the notion that the United States government was a feeble,

imbecile concern, and unable to restrain or punish them. The British

traders along the lake country furnished supplies, and fostered the

impression of the inability of the government to protect its

frontier population. The character and policy of Indians were wholly

misunderstood by the administration. War and plunder are the delight

of savage ambition. The little marauding parties that did such

repeated acts of mischief and cruelty to the settlements were

exactly in accordance with the habits and taste of the Indian

tribes.

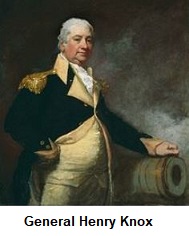

But the surprise at this day, is that General Knox, a veteran

Revolutionary officer, and a sterling patriot, should have been so

misled. General George Rogers Clarke had taught the nation how to

make Indians peaceable and bring them to terms in his Illinois

enterprise. He never solicited peace from a single tribe, but made

them think he was indifferent about it and rather preferred to

exterminate them. He knew the Indians naturally are cowards, and by

operating on their fears, brought them to beg peace of him. By this

method, peace was made with the tribes of Illinois Indians in 1778,

and they continued at peace during the eruption of the Kickapoos and

Shawnees. The United States, during the first term of Washington’s

administration, tried the experiment of “moral suasion,” and made an

effectual failure, until repeated disasters compelled the government

to a policy radically different from either measure recommended by

General Knox. They organized an army under the command of General

Wayde, who penetrated into the Indian country, burnt their villages,

destroyed their cornfields, and compelled them to beg for peace, or

to use the barbarous English employed more recently, the government

“conquered a peace.” We are surprised that the sagacious Secretary

of War did not foresee that permanent peace could not be obtained of

Indians by appeals to their benevolence, philanthropy, or justice;

and that the only method to prevent their extermination was to send

a strong force at once into their country, make them feel the strong

arm of government, and bring them at once to subjection. A vast

amount of suffering would have been prevented, and preservation of

life might have been gained by such a policy.

The President, in his official instructions to Governor St. Clair,

dated October 6, 1789, said: “I would have it observed forcibly,

that a war with the Wabash Indians ought to be avoided by all means

consistently with the security of the troops and the national

dignity. In the exercise of the present indiscriminate hostilities,

it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to say that a war

without further measures would be just on the part of the United

States. But, if after manifesting clearly to the Indians the

disposition of the general government for the preservation of peace,

and the extension of a just protection to the said Indians, should

they continue their incursions, the United States will be

constrained to punish them with severity.”

The peace begging policy of Washington was tried effectually, the

experiment proved a failure. The Indians, after repeated periods of

peace, continued their “incursions.” Many hundreds of families were

murdered. Two half-formed, deficient, and ill-provided armies, under

Generals Harmer and St. Clair, were defeated, and at a great loss of

blood and treasure, the United States government had “to punish them

with severity” by General Wayne. Half of the expense and a tithe of

the loss of life would have “conquered a peace” at the commencement.

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS, NO. 7

By an Old Resident

Source: Alton Telegraph, June 09, 1848

In a former communication, we have shown that the character,

talents, habits, and qualifications for self-government of the

pioneers of the West have been mistaken, and greatly underrated in

the older communities of the Atlantic States. This is more

particularly the case in New England. Amongst all the great and good

things that have pertained to Yankeedom, the descendants of the

Puritans have some great and glaring faults. One of these is a

distinctive trait of character, and shows itself on all occasions.

It is the firm and obstinate opinion that, to them, and their

peculiarities of manners, religion, morals, intelligence,

enterprise, and industry, exclusively belongs the credit of all that

is good, noble, philanthropic, and virtuous in the United States.

This habit of self-glorification may do well enough in him, but when

it assumes the form of supervision over their neighbors in our new

settlements, who with equal pertinacity think they know a few

things, and are nearly as good Christians and citizens, it becomes a

little annoying.

The pioneers of Illinois originated, in most instances, from the

Southern and Middle States, through the medium of Kentucky and

Tennessee, and brought with them the habits and modes of thinking

common to those districts. In their manners and customs, there were

some strongly marked circumstances:

1. They were rough and unrefined in their persons, manners, dress,

and mode of living, yet king, generous, warm-hearted, sociable, and

given to hospitality.

2. They were hunters, and stock-growers, and much of their

subsistence was derived from the range.

3. They were brave, prompt, and energetic in war, yet liberal and

magnanimous to a subdued foe.

4. They exhibited great energy and a just spirit of enterprise in

removing to a wilderness country and preparing the way for the

future prosperity of their descendants, and the immigrants who have

poured into the country.

5. They were hospitable and generous to each other and to strangers,

ready to share with the destitute their last resources.

6. They had a species of faith in Divine Providence – a presentiment

that their labors, toils, and sacrifices were preparing the way for

future prosperity even to other generations. They were guided by

Providence, preserved amidst dangers, perils, sickness, and savage

assaults, and thus became the pioneers of civilization and the

founders of free government, and the establishment in the hearts of

the people of a pure and enlightened Christianity. They turned the

wilderness into a fruitful field, and opened the country to a more

dense population.

7. Their habits and manners were plain, simple, and unostentatious.

In utensils, furniture, and dress, the most simple and economical

possible were all they could obtain. Not a single thing was used for

ornament, display, or show. No one paid taxes for the benefit of his

neighbor’s eyes.

It is no disparagement or reproach to the pioneers of Illinois, or

any other country, to say they were inured to labor, to danger, and

to rough living. Few others could have encountered the dangers and

difficulties of planting the standard of religion and civilization

on the wild prairies of the West.

The dunes of the household were discharged by the female sex, who

attended the dairy, performed the culinary operations, spun, wove,

and made up the garments for the whole family, carried the water

from the springs, and performed much other laborious service from

which females, and especially mothers, in a more advanced state of

society are exempted. Add to all this, each wife usually bred and

raised from ten to fifteen children, of which, in proof of the

healthfulness of the country, about nine-tenths of the children born

grew up to adult age. The statistics of hundreds of families in the

frontier settlements of the West furnish proofs of this statement.

The building of forts, or “stations,” and cabins, clearing and

fencing land, hunting game in the woods, defending the stations from

Indian assaults, and planting, cultivating and gathering the crops,

of which the Indian corn was the chief, were the appropriate

business of the men; though the other sex not unfrequently aided

their fathers, brothers, and husbands in field labor. In war, when

the stations were attacked, it was not unusual for females to mould

bullets and load the rifles at the stations.

And let not the impression be made that females who are reared under

such circumstances are necessarily low-minded, vulgar, uncouth, and

ignorant. Far from it. We can point to some who were the mothers of

our most eminent statesmen, who in after life graced the

drawing-room, whose intellectual qualities were of a high order, and

who in point of elevation of character, vigor of intellect, enabling

feelings and uncommon sense, were immeasurably in advance of the

pale, sickly, effeminate, silly, sentimental, boarding school

triflers of fashionable life. As an illustration, we will give an

anecdote of Esther Fuller, who was the wife of William Whitley – one

of the pioneers of Kentucky, and well known in the history of that

State:

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS, NO. 8

By an Old Resident

Source: Alton Telegraph, June 16, 1848

The pioneers of Illinois brought little other property than such as

they could pack on horses or carry on watercraft. A few implements

of husbandry in the most simple form, and such culinary utensils as

were indispensable, and confined to a very few articles; the rifle,

the axe, auger, saw, and very few other tools used by the mechanic

[laborer] were all that was deemed necessary. The primitive Western

log cabin, with its clapboard roof held on by poles, its stick and

clay chimney, its floor of split slabs called puncheons, and its

door, made of boards split from a log, smoothed with a

drawing-knife, united together with wooden hinges and fastened with

a wooden latch, was the uniform style of architecture. Not a nail or

any other piece of metal was used; not a pane of glass kept out the

air and storm from the aperture left for a window; all was wood, and

all constructed by the backwoodsmen.

With the first immigration, there were no regular mechanics, and for

some years after, but few are found in new settlements. The pioneer

learns to make everything he wants. Besides clearing the land,

making fence, building his cabin, corn-crib and stable, he must

stack his plough, repair his cart or wagon, make his ox yokes and

harness for his horses, tan his own leather, dress his deer skins,

cobble his shoes and those of his family, construct his own band or

horse mill, and not unfrequently becomes a rude blacksmith and

gunsmith for his neighbors. He learns to supply all his wants from

the forest. The tables, bedsteads, and substitutes for chairs are of

his rude manufacture. The stranger and traveler, accustomed to an

entirely different mode of life as he passes through the thinly

populated settlement, is struck and vexed with the peculiarly

uncomfortable situation and appearance of everything about this

people – their cabins are rude, and as he imagines, distressingly

uncomfortable. Their agriculture is quite primitive, their

implements and furniture coarse and unsightly, and everything in his

prejudiced imagination looks wrong and wretched. The roads are mere

“bridle paths,” the strams are unbridged, he sees “no tall spire

pointing to the skies,” and hears not “the sound of the church going

bell.” All in his estimation is a “moral waste.” The people, he

fancies, are ignorant, indolent, and vicious, and should he be the

correspondent of some religious paper away East, a long and doleful

jeremiad is contained in his next epistle.

But he is wholly mistaken in imagining the people to be ignorant,

indolent, and improvident. The backwoodsman has many substantial

comforts. In a few years, he is surrounded with plenty – his cattle,

swine, and poultry multiply around him. The fertile soil yields

prolific crops. His table is profusely supplied. He lives in a brick

house, his furniture is comfortable, and even elegant, and

hospitality and kindness are predominant virtues.

In this picture, we have described from personal observation the

pioneers into the counties of Morgan and Sangamon, and there are

many now living who can attest the correctness of our portraiture.

Twenty-five years ago, every house in Springfield was a primitive

log cabin, except occasionally a small glass window in the aperture.

The first courthouse was a rude cabin of round logs, the roof made

of split clapboards, and the floor of earth. In the “olden times,”

in Southern Illinois, as in all other primitive settlements of the

West, deer skins were used for clothing, made into hunting shirts,

pantaloons, leggings, and moccasins. The skin of the wolf and fox

was a substitute for the hat and cap. Strips of buffalo hide were

used for rope and traces, and the dressed skins of the buffalo, bear

and elk furnished the principal part of the bed at night. Wooden

vessels, either dug out or coopered, were the common substitute for

bowls for table use, from which the family ate their mush and milk.

The small-sized gourd constituted the drinking cup. Every hunter

carried his knife, while not unfrequently, the rest of the family

had one or two old case knives between them. If a family chanced to

have a few pewter dishes and spoons, knives and forks, cups, and

platters, they were quite in advance of their neighbors. Corn, for

bread and mush, was beaten in the mortar or ground in a hand mill.

Hospitality and kindness were prominent among the virtues of the

pioneers of the West. Deliver us, above all things, from the

neighborhood of that class of people who are moody, unsocial, and so

selfish and inhospitable as never to invite a neighbor or even a

stranger who may happen to be present, to share in the hospitality

of the family meals. Such people ought to live in a clan by

themselves, where they can indulge in the unmixed passion of

selfishness and quarrel, and threaten “to take the law” of each

other to their heart’s content.

The pioneers of whom we are writing were exposed to common dangers,

and became united by the closest ties of social intercourse.

Accustomed to arm in each other’s defense, to aid in each other’s

labor, to assist in the affectionate duty of nursing the sick, and

the mournful office of burying the dead, the best affections of the

heart were brought into habitual exercise.

There are peculiarities of habits and character between the North

and the South – the puritans of New England and the chivalry of

Virginia, but the origin and cause of this diversity are wholly

overlooked by the great multitude. Many superficial observers take

it for granted that the peculiar features of Southern character have

been formed by slavery. The descendants of the puritans

conscientiously believe in the superiority of their forefathers, and

thank God that they are not as other men, and especially those born

South of the Potomac and Ohio Rivers. One class attributes the

diversities of character to the influences of cotton and tobacco,

and the other to accidental circumstances.

Now the facts are these: The peculiarities of New England character

of both good and evil qualities can be traced back to the peculiar

habits and feelings from the rise of puritanism in Scotland and

England. It attained its zenith in Cromwell’s day, but continued to

send out a stream of influence during the seventeenth century.

Virginia, as a type of the South, received the peculiar traits of

character from the cavalier class, from which the chief portion of

the early settlers came. Whoever will carefully study the peculiar

shades of character that mark distinctly each of these classes, as

they were manifested in England and Scotland, from one hundred and

fifty to three hundred years since, will find the elements that make

up the light and shade of character peculiar to the North and South.

The prevailing elements of character in Illinois will be the

strongly marked lineaments of each, modified by other influences and

the commingling of other streams.

FIRST WHITE SETTLEMENT IN ILLINOIS - PEORIA

Source: Alton Telegraph, September 26, 1873

The generally received opinion is that Kaskaskia and Cahokia,

founded by the French, were the first white settlements in Illinois.

Such is the information given in many histories and geographies, and

such the tradition held by the present inhabitants of those

localities. But from a late, somewhat painstaking examination of the

early history of Illinois, we are inclined to the belief that

another section of the State is entitled to the honor. We refer to

the country in the immediate vicinity of the present beautiful and

prosperous city of Peoria. Of course, the history of the early

period when Illinois first became known is confused and

contradictory. It is difficult to separate history from tradition,

but from the best authorities we can obtain, it seems positive that

the vicinity of Peoria was settled by the French under LaSalle in

1680, and Kaskaskia and Cahokia in 1682 or 1683, by other parties of

French, also under LaSalle, returning from explorations of the lower

Mississippi. Our authority for this belief is from Governor John

Reynolds, who wrote, “My Own Times.”

“Peoria is the most ancient settlement west of the Alleghanies. On

the lake east of the present city of Peoria, LaSalle, with his

party, made a small fort in 1680, and from his hardships called it

and the lake Creve Coeur – in English, “Broken Heart.” Indian

traders and others engaged mostly in that commerce resided on the

“Old Fort,” as it was called, from the time LaSalle erected the fort

in 1680, down to the year 1781, when John Baptist Maillet made a new

location and village, about one mile and a half west of the old

village, at the outlet of the lake. This was called La Ville de

Maillet, that is, Maillet City. In 1781, the Indians under British

influence drove off the inhabitants from Peoria, but at the peace of

1783, they returned again. In 1812, Captain Craig (of the Illinois

militia) wantonly destroyed the village, but the city of Peoria at

present occupies the site of the village of Maillet, and bids fair

to become one of the largest cities in Illinois.”

In regard to destruction of Peoria by Captain Craig, Reynolds,

elsewhere in his history, says:

“While the army were in the neighborhood of Peoria, Captain Craig

had his boat lying in the lake adjacent to Peoria. He was attacked

several times by the Indians, but received no injury. The Captain,

supposing the few inhabitants of Peoria favored the Indians, burnt

the village. This was considered by everyone a useless act. He

placed the inhabitants of Peoria, all he could capture, onboard his

boat and landed them on the bank of the river below the present site

of Alton.”

John M. Peck, in his history of Illinois, after detailing the

discovery of the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers in 1673 by Pere

Marquette and Joliet, speaks of the subsequent exploring expedition

of LaSalle, who left France in 1678, reached the present site of

Chicago in November 1679, and in the December following, or in

January 1680 (same date as given by Reynolds) he reached the

Illinois River and descended until his supplies gave out, when he

was compelled to land and build a fort, which he called Creve Coeur.

Peck locates this fort near what is now Spring Bay in Woodford

County, several miles northeast of Peoria. But in this case, we

prefer the authority of Reynolds, who was not only accurately versed

in the early French history of the State, but had, as a Ranger,

thoroughly explored that country, when with other soldiers from

Madison and St. Clair Counties, he assisted, in 1812, in building

Fort Clark, on the present site of Peoria, and named it after

General George Rogers Clark, who conquered Illinois from the British

in 1778. Peck also states that LaSalle, after building Creve Coeur,

visited Canada, and again returned and descended the Illinois to the

Mississippi, and the latter to its mouth. ‘On returning, he left

some of his companions to occupy the country, which is supposed to

have been the commencement of the villages of Kaskaskia and

Cahokia.’ As LaSalle sailed for France in 1683, these villages must

have been founded in 1682, two years later than Peoria.

Reynolds confirms Peck’s statement in regard to Kaskaskia as

follows:

“The Rev. Father Alloues, about the year 1682, established the first

white Christian congregation in the West, at the Indian village of

Kaskaskia, the same site which Kaskaskia now occupies; about the

same time Father Pinet founded a church at the present site of

Cahokia.”

Another important authority, confirmatory of Reynolds’ statements,

both as regards the date of founding and exact location of Creve

Coeur, is J. W. Foster, LL.D., author of “the Mississippi Valley,”

and President of the American Association for the Advancement of

Science. In regard to LaSalle’s explorations, he speaks as below:

“LaSalle and his party, on the 30th of January, 1680, reached Peoria

Lake, then called Pimitoni. The next day they passed the expanded

waters to where they again contract within the ordinary limits. Here

they encountered an encampment of Indians. Alarmed at reports of the

ferocity of the savages, and also by dissension among his followers,

LaSalle at once set to work to entrench himself. For this purpose,

he selected a site a mile and a half below his camp (which, it will

be remembered, was at the lower extremity of the lake), on the

southern bank of the stream, three hundred yards from the water’s

edge. It was a knoll, intersected on each side by a ravine, while in

front the low ground was subject to overflow. Here he built a fort,

which he named Creve Coeur, as expressive of his misfortunes. Traces

of the embankments thus thrown up are yet discernable. This was the

first civilized occupation of Illinois.”

In relation to Kaskaskia, Foster says, “It was probably founded

about 1683.” This is three years later than the founding of Creve

Coeur, but we think other evidence indicates that 1682 is the date

of Kaskaskia’s settlement.

This testimony of Foster is most important. It confirms Reynolds’

account both as to the time Creve Coeur was founded, and the

particular site. It also confirms Peck’s date in regard to the

founding, but corrects his conjecture that the site of the old fort

was near Spring Bay. Reynolds, it will be noticed, asserts

positively that Creve Coeur was occupied continuously by the French

for over one hundred years, or until 1781, when they removed to the

present site of Peoria, one and a half miles west, which settlement

has continued to the present day. It seems conclusive, then, that

the vicinity of Peoria is the oldest settlement in Illinois, at

least two years the senior of Kaskaskia and Cahokia, which have

hitherto claimed the honor of being the oldest settlements in the

State.

HISTORICAL NOTES ON ILLINOIS

Source: Alton Telegraph, November 14, 1873

In 1766, the first negro slaves, 500 in number, were brought to

Illinois by Phillip Francis Renault, to work the mines. Their

descendants can still be found in Randolph County.

On February 16, 1763, the Illinois Country, on the east side of the

Mississippi, was ceded by the French to the English. In 1764, the

English, by Captain Stirling, took possession of the country. The

white population of the whole State at that time was less than

2,000.

In the year 1778, during the war of the Revolution, Illinois was

conquered from the British by the distinguished American General,

George Rogers Clark. His campaign was one of the most brilliant

achievements of the Revolution. His army consisted of 153 men. With

that small force, he captured the strong forts at Kaskaskia and

Vincennes, and conquered the whole region. The fort at the former

place was captured on July 4, 1778, and Cahokia was occupied

immediately thereafter. A government was then organized under

authority of the State of Virginia, which has remained with various

amendments to the present time.