Lincoln - Douglas Debate

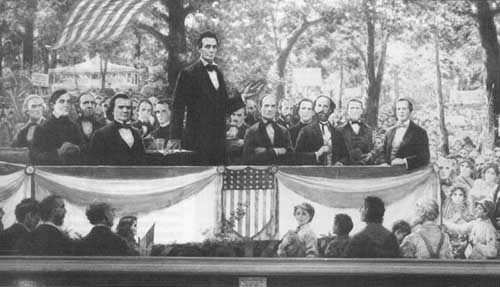

On October 15, 1858, the seventh debate between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, for the Illinois Senate seat, was held in Alton, Illinois. In July 1858, Lincoln challenged Douglas to a series of debates, which were held throughout the State. Douglas was an incumbent Democrat, and Lincoln was a former Whig, turned Republican. At around 1:00 p.m., approximately 5,000 citizens gathered at the northeast corner of the Alton City Hall, where a large stand, decorated in patriotic bunting, had been erected. Seating was provided for the ladies. The Chicago and Alton Railroad provided half-priced train fare for the event, while others came by steamboat, horse, or by foot. Lincoln and Douglas had arrived by steamboat, coming down from Quincy, Illinois, before daybreak. Lincoln received friends at the Franklin House on State Street, while Douglas received friends at the Alton House on Front Street. A military company paraded through the streets, accompanied by a band. Excitement was in the air, and people walked up and down the streets of Alton, cheering on their favorite candidate, while businesses were decorated with banners of their chosen party. Below are the newspaper articles chronicling the event in detail. Although Lincoln lost the Senatorial election to Douglas, he gained a wide reputation through his speeches, and went on to become the 16th President of the United States in 1861.

MAKING ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE LAST GREAT DISCUSSION

Lincoln – Douglas Debate in Alton

Source: Alton Weekly Courier, October 14, 1858

Let all take notice, that on Friday next, Hon. S. A. Douglas and

Hon. Abraham Lincoln will hold the seventh and closing joint debate

of the canvass at this place [Alton]. We hope the country will turn

out to hear these gentlemen. The following programme for the

discussion has been decided upon by the Joint Committee appointed by

the People’s Party Club and the Democratic Club for that purpose.

Arrangements for the 15th inst.:

The two committees – one from each party – heretofore appointed to

make arrangements for the public speaking on the 15th inst., met in

joint committee, and the following programme of proceedings was

adopted, viz:

1. The place for said speaking shall be on the east side of City

Hall.

2. The time shall be 1:30 o’clock p.m., on said day.

3. That Messrs. C. Stigleman and W. T. Miller be a committee to

erect a platform; also, seats to accommodate ladies.

4. That Messrs. B. F. Barry and William Post superintend music and

salutes.

5. Messrs. H. G. McPike and W. C. Quigley be a committee having

charge of the platform, and reception of ladies, and have power to

appoint assistants.

6. That the reception of Messrs. Douglas and Lincoln shall be a

quiet one, and no public display.

7. That no banner or motto, except national colors, shall be allowed

on the speakers’ stand.

On motion, a committee, consisting of Messrs. W. C. Quigley and H.

G. McPike be appointed to publish this programme of proceedings.

Signed, W. C. Quigley and Henry G. McPike

Note: To the above, it should be added that the Chicago, Alton & St.

Louis Railroad will, on Friday, carry passengers to and from this

city at half its usual rates. Persons can come in on the 10:40 a.m.

train, and go out at 6:20 in the evening.

LAST JOINT DEBATE BETWEEN LINCOLN AND DOUGLAS

Source: Alton Weekly Courier, October 21, 1858

The seventh and closing debate between Messrs. Douglas and Lincoln

came off at this city [Alton] yesterday afternoon. The day was not

the best – the morning being somewhat cloudy with indications of

rain. At an early hour, the country began to arrive. It came on foot

– on horseback – by carriage – by lumber-wagon – and by all other

conveyances possible. The steamer “Baltimore,” from St. Louis,

brought up its load of those desirous to hear the great debate. At

half past ten o’clock, the train on the Chicago, Alton & St. Louis

Railroad, freighted with its gatherings from Springfield, Auburn,

Girard, Carlinville, Brighton, Monticello [Godfrey], and we know not

how many other towns, steamed slowly into the city with its burden

of eight rail cars. The other passenger trains of the forenoon and

early part of the afternoon demonstrated, too, that the names of

Lincoln and Douglas have a hold upon the country. About noon, the

extra steamer, “White Cloud,” landed upon the levee with its quota

of the denizens of St. Louis. With the earliest arrival, the rooms

of Messrs. Douglas and Lincoln, who reached the city before daylight

– coming down the river from Quincy – became the centers of

attraction. Mr. Lincoln received at the Franklin House, and Mr.

Douglas at the Alton House. The train of the Chicago, Alton & St.

Louis Railroad brought down the Springfield Cadets, a fine military

company, who paraded through our streets, accompanied by Merritt’s

Coronet Band, discoursing sweet music. At a later hour, the band of

the Edwardsville delegation also gave us a display of its power “to

charm the sense and soothe dull care away.”

By the hour of 12:00, the great American people had taken possession

of the city. It went up and down the streets – it hurrahed for

Lincoln and hurrahed for Douglas – it crowded to the auction rooms –

it thronged the stores of our merchants – it gathered on the street

corners and discussed politics – it shook its fists and talked

loudly – it mounted boxes and cried the virtues of Pain Killer – it

mustered to the eating saloons, and did not forget the drinking

saloons – it was here and there and everywhere, asserting its

privileges and maintaining its rights. Immediately thereafter,

couples and triplets and singles of its 6,000 component parts betook

themselves to the neighborhood of the stand prepared for the

speaking.

Over the stand, which was located on the eastern side of the City

Hall and Market building, the Stars and Stripes floated out upon the

breeze. Mr. Henry Lea displayed several banners and flags. One was

inscribed “Illinois born under the Ordinance of 1887 – she will

maintain its provision,” another, “Lincoln not yet trotted out,” and

a third, “Free Territories and Free Men. Free Pulpits and Free

Preachers. Free Press and a Free Pen. Free Schools and Free

Teachers.”

Mr. E. H. Goulding notified everybody in this style, “Squat Row for

‘Old Abe’ and Free Labor.” A cord stretched from the store of Mr.

Isaac Scarritt to that occupied by Dr. Bow & Barr, sustained a large

flag bearing the mottoes, “Old Madison for Lincoln,” and “Too late

for the Milking.” The national colors floated proudly from the

flagstaff of the Courier office.

The Douglas men concentrated their whole energies in one grand,

magnificent, superb, right-royal banner, which was suspended over

Third Street, between the store of Mr. Henry Lee and the Baok

Building. The words, “Popular Sovereignty,” “National Union,” and

“S. A. Douglas, the People’s Choice,” were surmounted by a very

buzzard-like bird, ready poised to swoop down upon his prey, and

surrounded by five stars, intended, as we suppose, to represent the

four states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Iowa, which have

already put their knives to the throat of Mr. Douglas, and Illinois,

which will do so in November, after which he will be ready,

politically, for the buzzard.

The hour of two having nearly arrived, the great American people,

having gathered all its parts, or so many of them as would consent

to be gathered to the first floor of the city hall building, and the

ground between that and the Presbyterian Church, Messrs. Lincoln and

Douglas made their appearance upon the stand.

As previously agreed, Judge Douglas opened the debate in a speech of

an hour. Although appearing very well, his voice was completely

shattered, and his articulation so very much impeded that very few

of the large crowd he addressed could understand an entire sentence.

Nearly all his speech was a repetition of his previous charges of

amalgamation, negro-equality, &c., against the Republican Party; and

he labored and twisted them, and rolled them as sweet morsels under

his tongue, till his own friends were disgusted with his pertinacity

and falsehood. Having nearly exhausted himself and his hour also on

this terrible bug-bear, the Judge then ventured upon one of the most

important, and to him, the most fearful act of his life. He actually

attacked Buchanan and his administration, and berated them to his

heart’s content. His friends here were not prepared for this bold

step on the part of their leader, and opened wide their eyes in

astonishment. What – had their Little Giant – their terrible leader

stood so long calmly and meekly by when the heads of his friends,

one after another in rapid succession, rolled before him in the

dust, and not a word of rebuke or condemnation! And now, at the very

heels of an election, more important to him than any other of his

life, he plucks up courage and denounces the President in terms

admitting of no mistake as to his feelings. With this exception, his

speech was not different from his previous efforts. It was flat and

unsatisfactory, unredeemed by a single sparkle of wit or patriotic

elevation.

The hour and a half reply of Mr. Lincoln was an effort of which his

friends had every reason to be proud. One by one, he took up the

oft-exploded charges of Douglas against the Republican Party, and

scattered them to the winds, and charged back upon him his own army

of sins of omission and commission, with terrible effect. Not a

single point was left unanswered of all the charges Douglas made,

and so convincing was the array of testimony he produced, so clear

and logical every deduction drawn from them, and so honest and

candid was he in all his assertions, the Douglasites themselves were

forced to admit that they had not only underrated the native

strength of the man, but that he was greatly misrepresented in their

papers. His reply was, in fact, a complete vindication of himself

and the Republican Party, from the foul slanders sought to be heaped

upon them, and as a vindication, could not be successfully answered.

Douglas’ half-hour rejoinder was both in better spirit and better

taste than his opening. It was not, in fact, a rejoinder at all. It

was principally a series of charges against Mr. Lincoln about his

Mexican War votes, which he then introduced so that Mr. Lincoln

could have no opportunity of replying. Brave Little Giant! Cunning

Little Giant! Magnanimous Little Giant!

As we intend to publish the speeches in full in a few days, we shall

not further speak of them now. The discussion has been longed for by

the Republicans of this city and vicinity, and their expectations

have been more than realized. As the Democracy of the States of

Iowa, Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania has been thrashed out, so was

Mr. Douglas thrashed out by Mr. Lincoln yesterday.

DOUGLAS MEETING HELD LAST NIGHT

Source: Alton Weekly Courier, October 21, 1858

The Douglasites held a meeting last night opposite the bank, just

under that great buzzard displayed across the street. J. H. Sloss,

Esq., Douglas candidate for the Legislature, Spread-Eagle Merrick of

Chicago, H. W. Billings, Esq., of Alton, Railroad Attorney Z. B.

Job, Esq., railroad candidate for the Legislature, and J. E.

Coppinger, Esq., anti-railroad, were the speakers.

Sloss made a very fair talk with but little effect. Spread-Eagle

Merrick mounted his favorite bird and had not got down to earth when

we went to press. Billings whispered railroad – talked railroad –

screamed railroad - blessed the Courier - and announced his

intention to make an exclusive railroad speech. Job railroaded

everything, Jon Gillespie included, giving the impression that he

was running against Joe for the Senate. He admitted he could not

make a speech, and all agreed with him.

Coppinger spoke next. He said he was not a candidate (away went one

of the lanterns); that he had served the people in the city council

(two more lanterns removed and one of Post’s store doors closed);

that he was opposed to railroads (all the lights taken away and

doors closed); and that he would not support Buck (the box on which

he stood was here knocked from under him by the Douglas

Railroaders); and the meeting adjourned sine die.

DOUGLAS CORNERED – REFUSES TO ANSWER

Source: Alton Weekly Courier, October 21, 1858

Yesterday, Douglas kept his temper until Dr. Hope got after him, and

then he flew into a rage and called the Doctor an ally of the

Abolitionists. The occasion was this: Dr. Hope stepped up to Douglas

after the speaking was over, and asked him if he would permit Hon.

F. P. Blair to state what conversations took place last winter

between them. The Little Giant flew into a rage, called Hope an

associate and ally of the Abolitionists, and flatly and pointedly

refused to permit Blair to tell a word. Blair knows something,

evidently.

DR. THOMAS HOPE GIVES A SPEECH

Source: Alton Weekly Courier, October 21, 1858

Last evening there was assembled at Temperance Hall the largest

Democratic meeting which has been held in the city the present

canvass. The occasion was a speech from Dr. Hope, the Administration

candidate for Congress in this district. The Republicans, according

to the Doctor, were very bad indeed, but oh, their smell was nothing

compared to the Douglasites. The occasion was embraced to pay

particular attention to Messrs. Billings and Metcalf of Alton, and

other recent converts to Douglasisms, and his review of their course

was a scathing one.

The Doctor has a holy horror of abolitionism, and for him to be

charged with being its ally, as was charged upon him by Douglas a

few days ago, appeared to excite his utmost ire. The way he

denounced the Little Giant was anything but pleasing to his friends.

That part of it the Republicans did enjoy, certainly.

The speech was full of statistical information, having evidently

been prepared with considerable care, and was well delivered.

Democrats present pronounce it the best speech the Doctor ever

delivered.

THE SPRINGFIELD CADETS

At the Lincoln-Douglas Debates

Source: Alton Weekly Courier, October 21, 1858

The Springfield Cadets visited our city on the occasion of the joint

debate between Lincoln and Douglas, and their beautiful appearance

and excellent training merit a notice from us. Their officers are as

follows: Captain Mather; First Lieutenant W. H. Lathan; Second

Lieutenant Lloyd; and Third Lieutenant Strichlen.

Immediately after the arrival of the 10:30 o’clock train, on which

they came down, they formed, and preceded by Merrit’s Cornet Band,

which by the way, is one of the finest that has visited our city

lately, they paraded through our principal streets, attracting

general attention. In the afternoon, at the cease of the discussion,

they again formed, and after marching about the city awhile down in

front of the Courier office, they displayed their knowledge of

military tactics. Their evolutions were exceedingly well performed.

They drew a large crowd of observers, and well they might. The

beauty of their uniforms, their general neatness of appearance, the

certainty and rapidity with which they moved at the word of command,

combined to make them justly admired and praised.

THIRTY-EIGHTH ANNIVERSARY OF LINCOLN – DOUGLAS DEBATE

Source: Alton Telegraph, October 15, 1896

October 15 is the 38th anniversary of the seventh and closing debate

between Lincoln and Douglas in Alton, which took place on October

15, 1858. The debate took place from the east door of the city hall

building. The square from the city hall to the Presbyterian Church,

and from the spot where Union Station now is to the north side of

Second Street [Broadway] was densely packed with people. A platform

was erected in front of the east door of the city hall, from which

Lincoln and Douglas addressed the immense audience. A fair estimate

of those present placed it at 6,000 or 7,000.

Douglas said in Alton that “He did not care whether slavery was

voted up or voted down.” In Lincoln’s reply, his face glowed as if

tinged with a halo, and he looked the prophet of hope and joy, when

with dignity and emphasis he said, “That the question of slavery was

a question of RIGHT and WRONG.” “That,” said Mr. Lincoln, “is the

real issue. That is the issue that will continue in this country

when these poor tongues of Judge Douglas and myself shall be silent.

It is the eternal struggle between these two principles, right and

wrong, throughout the world. They are the two principles that have

stood face to face from the beginning of time, and will ever

continue to struggle until the common right of humanity shall

ultimately triumph.”

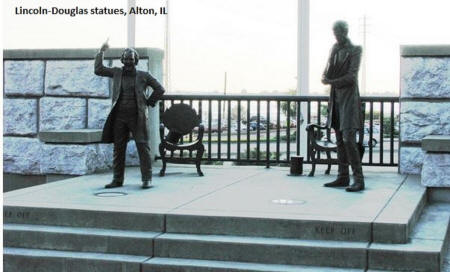

EX-GODFREY RESIDENT URGES BRONZE STATUTES OF LINCOLN & DOUGLAS -

WAS AT THE DEBATE

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, September 5, 1906

Former Mayor H. G. McPike has received the following letter from Dr.

James Squire, formerly of Godfrey, now practicing his profession in

Carrollton, Ill., and is self-explanatory:

"Dear Sir: I saw the statement in a St. Louis paper you made about

the debate between Lincoln and Douglas in Alton in 1858. I was

there, and as a boy climbed up on the platform on the east side of

the Alton City Hall and sat there at the feet of Lincoln and

Douglas. I remember how they looked and spoke - remember the sweet,

pleasant smiles and ringing invectives, and great truths expounded

by Lincoln; the poor voice and oratorical gestures of the 'Little

Giant,' Douglas, who was plainly out of health, or 'cornered,' and

could not answer the man who proclaimed the doctrines of the

emancipation - who said, 'this government cannot stand one-half

slave, one-half free,' etc. I have always quoted that day and my

position on the platform as one of the bright days and spots of my

history, and have often thought as I passed along how nice it would

be to see those men in bronze statues, one on each side of that

place, on a pedestal, and it would be attractive to all people

visiting Alton. Beautify that hallowed spot! The last meeting place

of the two greatest men of Illinois, if not of this country, as the

speech delivered that day in Alton made Lincoln President and

secured emancipation. The legislature should make an appropriation

to help erect the statues, and if Madison county will elect men of

strong character to represent her in the legislature, no doubt help

could be secured in part from the state to commemorate those two

giants and that one spot. You, as presiding officer of that meeting,

Mr. McPike, should start this movement, and I know you can, and

believe you will inaugurate it and see that it reaches a successful

consummation. I write this only to congratulate you on the accuracy

of the details of that debate as given by you between the two

greatest men on earth at that time, 1858. I am willing to do

anything I can to help, and I urge that justice be done to the

debaters and I also am anxious to show that Alton was on the map in

the past, and I hope she will be in the future as a 'great city.'"

ALTON LADY REMEMBERS DEBATE DISTINCTLY

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, December 18, 1907

Mrs. Catherine Dietschy, widow of Joseph Dietschy, who resides at

614 East Fourth Street, is one of the surviving Altonians who

listened to the Lincoln-Douglas debate in this city, and she

remembers the occasion and much of the speech of Douglas distinctly.

She says there was a big crowd present on the east side of the city

hall, and that Douglas, who was a "little, short, heavy man," who

kept his head bobbing backwards and forward - sometimes violently

bobbing all through his speech. After the speaking she says Douglas

was taken to St. Louis on a handsomely decorated steamboat. The

Lincoln-Douglas organization might be able to secure some valuable

information from Mrs. Dietschy, and if not valuable, certainly some

interesting information concerning that verbal battle of

intellectual giants.

SURVIVORS OF LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATE

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, December 19, 1907

Below is a list of persons who sent their names to the Alton

Telegraph as having been present at the Lincoln-Douglas debate in

Alton, October 15, 1858. If no city of residence is given, they

resided in Alton. There is no doubt a large number of others living

in Alton and elsewhere whose names are not given.

Lucas Pfeifenberger

Mrs. K. Dietschy

Edmond Beall

John Haley

Edward Ashwell Smith

Fredrucj A. Hummert

Ferdinand Volbracht

John Diamond

Mrs. A. Johnston

Rev. Jotham A. Scarritt

John L. Blair

Edward P. Wade

L. H. Yager

Henry Guest McPike

Thomas M. Long

George H. Davis

George D. Hayden

Jacob L. Watkins

Joseph W. Cary

Henry Watson

Joseph Einsele

Louis Stiritz, Clifton Terrace

A. A. Neff

Ebenezer Marsh

Harry Basse

Landolin Walter

Frank H. Ferguson

Thomas Dimmock, St. Louis

Mrs. S. Sotier

George Dickson

J. Magnus Ryrie

George W. Carhart

William Jarman

Joseph I. Lamper

R. J. Young

Wolf Laudener

Dr. George Worden

L. H. Kelly

Emanuel H. Boals

George Henry Weigler

Albert Wade

Hiram S. Mathews

Christian Wuerker

George W. Cutter

Patrick J. Meiling

William Flynn

Gaius Paddock

Beda Schlageter

Charles Holden

Harrison Johnson

John Hoffman

Thomas O'Leary

John Bauer

Rudolph Maerdian

Archibald L. Daniels

John Mills Pearson, Godfrey

Nicholas Challacombe, Melville

Dr. Titus Paul Yerkes, Upper Alton

Capt. Henry A. Morgan, Upper Alton

R. R. McReynolds, Upper Alton

Capt. Troy Moore, Upper Alton

George Barclay Weed, Girard

Mrs. Letitia V. Rutherford

James Barr, Nevada, MO

Lewis Megowan, Upper Alton

Edwin M. Hugo, Upper Alton

Andrew Fuller Rodgers, Upper Alton

William R. Wright, Upper Alton

James Seyboldt, Troy

William Cowper McPike, Atchison, Kansas

John Seaton, Atchison, Kan.

Jacob Preuitt, Bethalto

Louis Houck, Cape Girardeau, MO

Dr. James Squires, Carrollton

Roger W. Atwood, Chicago

William Russell Prickett, Edwardsville

Christian Schwartz, Edwardsville

Shadrach Bond Gillham, Upper Alton

James W. Davis, St. Louis

Michael A. Lowe, Upper Alton

Dr. Joseph Pogue, Edwardsville

August Baker, Melville

NOTES:

The Abraham Lincoln – James Shields debate was held in Alton on

October 15, 1858. The debate was held outside the newly-constructed

Alton City Hall, located on what is today the Lincoln-Douglas Square

at the foot of Market Street.

LINCOLN-DOUGLAS STORIES BROUGHT OUT BY SEMI-CENTENNIAL

CELEBRATION OF DEBATE

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, December 20, 1907

Anent the proposed celebration in this city in October next year of

the debate between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas on October

15, 1858, many interesting stories are told of by the older people

of the occasion and the amenities that passed between the eminent

speakers on the occasion. Great interest was stirred among the

residents of the territory 75 to 100 miles around Alton. People came

in all kinds of vehicles, some of them traveling for two days and

nights. Some of them estimated the crowd at ten thousand, but this

no doubt is larger than the actual number.

Thomas M. Long, city engineer, then deputy United States marshal

under President Buchanan, happened to be in Edwardsville at the time

on business and organized a crowd to come over to Alton. Something

like twenty to thirty vehicles were used to convey the people from

the county seat. All along the way, Mr. Long says that the

procession was enlarged by farmers wagons filled with people, and

when the procession reached that part of the city where Washington

street now is, there must have been 200 vehicles of all kinds in

line. Mr. Long got a good position in company with the late Z. B.

Job and others, and heard the speakers distinctly. He says there was

intense feeling and much enthusiasm, and the points made by the

speakers were loudly applauded.

F. A. Hummert was at that time a lad, and with his father came in a

wagon from Fosterburg to attend the debate. Mr. Hummert has a very

vivid recollection of the men and what they said; of the crowd and

its great size, and of the way the partisans of the two men cheered

and applauded their favorites.

G. B. (Bradley) Weed was a boy at the time and lived in Alton and

attended the meeting. He tells of his feelings and give interesting

data of the occasion. Mr. Weed has lived in Girard since he moved

away from Alton, and is now practicing his profession, a druggist,

although he is 69 years of age. The writer remembers him well as

being one of the pupils of the old school that formerly was on the

site of the Garfield school.

R. J. Young says he was present and heard the debate. He says that

the speakers addressed each other as "Abe" and "Steve." During the

addresses Mr. Douglas said something about "Abe" which drew a long

and loud volley of applause from the Democratic section of the

crowd. After the applause, Mr. Lincoln responded: "Well Steve, I see

you have a big lot of friends here in this little city of Alton, but

there will be another time. You may beat me this time, but in the

next race the longest pole will knock the persimmon on the highest

limb." This was a remarkable prophecy, for Douglas did beat Lincoln

that time. Two years afterwards the two men were opposing candidates

for the Presidency, and Lincoln won the big persimmon. He carried

Alton, which had always been Democratic at prior elections, giving

Lincoln a majority of 13, and was in line with the entire North.

John S. Leeper of this city was present at the Freeport meeting and

gives his impressions of both men. After Douglas closed his part of

the debate in which he belabored Lincoln in his usually caustic and

telling manner, Lincoln arose, and with great solemnity announced:

"I now propose to stone Stephen." Stephen no doubt had many sore

spots on his anatomy as "Abe" threw political stones at Stephen

until the latter was almost ready to cry out. "Bold enough." There

was great good humor between the two men, and they were seen to walk

away from the meeting arm in arm and laughing over the jokes they

perpetrated on each other.

Charles S. Leech was among those who listened to the debate. He was

then as now a resident of Alton. He was 18 years of age at the time.

Mr. Leech was walking along Piasa street on his way to the speakers'

stand east of city hall. A few yards in front of him was Lincoln,

accompanied by Amasa Barry and B. B. Harris, both now deceased, and

heard part of the talk indulged in by the three men. Messrs. Barry

and Harris ..... [unreadable] Lincoln about ..... to engage in ....

"Little Giant," as .....in those days. Mr. Leech has a very distinct

recollection of Douglas' voice, something on the order of the baying

of an immense mastiff, "wow," "wow," as if at some distance. When

near Douglas his words came slow and deliberate, very distinct.

Lincoln, on the other hand, was a quick speaker, with a high-keyed

voice, and every word could be very plainly heard at a distance.

Charles A. Rodemeyer of Upper Alton says he remembers the debate

between Lincoln and Douglas, which occurred in 1858, as well as if

it occurred yesterday. He says he was a small boy then, but he was

always on hand when there was any excitement on and he stood very

close to the two speakers while they were talking and afterward

shook hands with Douglas. Mr. Rodemeyer says a man named Merritt

from Chicago spoke right after the debate and he has heard no one

say anything about that in speaking of the famous debate.

Mr. Edward Rogers, also of Upper Alton, says he remembers the debate

very distinctly and remembers many things said by both speakers.

ALTON WILL HAVE BIG ART EXHIBIT DURING LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATE

CELEBRATION

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, September 26, 1908

In another column will be found a local ad by W. H. Wiseman, the

photographer, who is asking Altonians and others to contribute to a

big art exhibit which will be given at his place, fort Wiseman,

October 12-17. St. Louis artists have already agreed to send some of

the finest collections of paintings, etc., ever seen in Alton, and

Mr. Wiseman himself will have on exhibition many remarkably fine

specimens of his own work done with his new $250 camera. There will

be on display a suit of armor taken from a Moro chief after he was

killed by a United States soldier in the Philippines during the

Spanish War. The armor is made of bronze and weighs seventy-five

pounds. The chief was a small man weighing only about ninety pounds,

and the exhibit for this alone will be of great interest. Among

other things to be displayed will be a five-foot-long photograph of

the Standard Oil refinery site and buildings, which was taken by Mr.

Wiseman for the Standard Oil company from a tower one hundred and

eight feet high, which was built especially for the purpose. This is

pronounced by those who have seen it to be the finest piece of

photographic work ever seen in Alton. Mr. Wiseman has also had a

tower built on the Alton bridge and from this he will take an eight

feet long photograph of Alton on the river front. He is waiting for

weather conditions to improve a little and the river to become

higher before taking this last picture. The exhibit will bring many

fine art specimens and curious things generally to Alton, and all

who can contribute to its interest ought to do so, as the studio

will probably be visited by thousands of out of town visitors during

the time the exhibition will be on.

BRONZE MEMORIAL TABLET ARRIVES FOR LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATE

MEMORIAL

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, October 6, 1908

The bronze memorial tablet to be placed on the city building to mark

the place where the famous closing debate between Abraham Lincoln

and Stephen A. Douglas took place October 15, 1858, arrived this

morning and is in the custody of Jacob Wead, who will make

arrangements for having it set in place. The tablet will be placed

on the panel in the east side of the city hall building, on the

Market street side, between the two fire escapes. It will be set

about eight feet from the ground to put it out of the way of people

who might deface it or mar its beauty in any way. The tablet is

severely plain. The lettering is raised and is of the plainest kind.

The inscription on the tablet is as follows: "1858-1908. Erected by

the Citizens of Alton commemorating the Closing Debate Between

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, which took place here,

October 15, 1858." The tablet will be set in place before the time

for its unveiling but will not be open to the view of the public

until the morning of October 15, when the veil will be drawn by John

Bowman, a son of Mr. and Mrs. Edward M. Bowman. Mr. Bowman is

chairman of the committee which is in charge of preparations for the

celebration and his son was chosen in recognition of is valuable

services in behalf of the semi-centennial.

SEMI-CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION OF LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATES

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, October 15, 1908

Fifty years ago today, the last of the series of debates between

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas took place at Alton. The

semi-centennial observance of the debate today was a gigantic

success. The interest in the anniversary celebration far exceeded

what was expected. Alton had been preparing for the anniversary day

by making a thorough house cleaning. The city never looked prettier

in her autumnal dress, and it never looked neater or cleaner after

the strenuous exertions of the city government. It never looked more

attractive either from the point of view of the artistic decorator.

The decorations were quite an important feature of the occasion, and

elicited many favorable comments from those who were back in their

old home to spend the day and see what Alton had been doing in the

many years they had been absent. Those who feared there might be

lack of interest in the celebration were greatly mistaken. It was

the reawakening of old memories to many of the old residents of

Alton. It aroused the interest of hundreds of one-time residents

here who flocked to Alton for the day from all parts of the country.

Some had come from Denver and other western points. Some were here

from New York, some from the north and some from the south. Alton's

homes were filled with guests. The hotels were filled and there were

many who had difficulty in finding places to stay. Among the

visitors were great numbers who heard the debate of fifty years ago.

The committee did not believe there would be so many, and the demand

for badges far exceeded the supply. Alton probably had more old

people in her borders today than she ever had in her history. The

hundreds of old men, ranging from 90 years of age downward to 62 and

63, who were here, made the occasion a notable one in this respect

alone. Among the oldest who were present as veterans and were given

seats in the carriages were Captain Troy Moore of Upper Alton and

Hon. George H. Weigler of Alton, both past 90 years of age and both

well preserved. There were other "younger" men who were between 80

and 90, the number of them being so large that it would require a

long roll to contain them. From that down to 60 years there were

many who had heard the debates and who had not been in Alton in many

years. The day was a complete counterpart of the date of the

original debate. The air was warm and balmy, the skies were blue and

everything in Nature helped to make the celebration what it was

desired it should be. Preceding the unveiling of the tablet was the

parade of the school children, military bodies and the city officers

and those of the celebration. It was a thrilling sight. The parade

was formed on Ridge street according to a plan prepared by the Grand

Marshal, Col. A. M. Jackson. One by one the bodies fell in line

marching down Second street toward the city hall. Fifteen hundred

flags had been provided for the children of the Alton and Upper

Alton public and parochial schools. There was not near enough, and

the younger children had been ruled out of the parade because they

were thought to be too young to march. The following was the

formation of the parade: Grand Marshal and aides from Alton High

school, mounted; automobiles and carriages, Western Military Academy

band and cadets, Naval Militia, Shurtleff college, Upper Alton

schools, Alton Y. M. C. A., White Hussars band, Board of Education,

High School and Garfield School pupils, St. Mary's pupils, Humboldt

school pupils, St. Patrick's and Cathedral schools, Lovejoy,

Douglas, Washington annex and McKinley annex schools, Lincoln and

Irving schools; reception committee, G. A. R. drum corps. The parade

started moving about 10:15 a.m. There was wild enthusiasm among the

marchers. Each section of the parade carried a banner denoting its

identity. When the city hall was reached by the marchers it was

almost impossible for the children to be massed in close enough to

hear anything of the program. The audience was packed solidly with

people who could not be moved, and after vainly trying to get close

enough to the speakers stand to hear what was going on, many

hundreds of the audience scattered out and moved around the city. An

incident of the gathering was the efforts of some of the old timers

trying to get themselves straightened out. They were puzzled coming

to the new Alton. They could not get their bearings, the changes had

been so radical since they came, and prior to the beginning of the

program the old folks were working hard to find out where some of

their old landmarks were and how to get around the city. At the

opening of the program the White Hussars band played and the

Invocation by Rev. Fr. E. L. Spalding, rector of SS. Peter and

Paul's Cathedral, followed. The formal presentation of the memorial

tablet by Rev. A. A. Tanner of the Congregational church followed.

Rev. Tanner made a lengthy and scholarly address, dwelling on the

historic features of the occasion. At the conclusion of his address,

the unveiling of the tablet was done by John Drummond Bowman, son of

Mr. and Mrs. E. M. Bowman. The tablet of bronze had been set in the

panel of the wall on the east side of the city hall building. It was

concealed by a curtain of two silk American flags, suspended from a

bar above them. At the appointed time the flags were drawn aside

amid the cheers of the audience. The acceptance of the tablet in

behalf of the city was done by Mayor Edmund Beall. Mayor Beall made

a short address in performing his official duty of acceptance. After

a beautiful address by General Alfred Orendorf of Springfield,

president of the Illinois Historical Society, which was the promoter

of the celebrations, the morning program closed.

Sidelights on Lincoln-Douglas Debate:

This morning there was a banner borne in the parade which was

carried fifty years ago by Ewing Dale of Edwardsville, a son of

Judge Dale. A brother of the deceased banner bearer brought the

banner to Alton this morning and displayed it. On the banner was the

inscription: "Dinna ye hear the Slogan, Tis Douglas and his Boys."

On the reverse of the banner was the inscription: "Douglas Blues."

William G. Pluckard of Chicago had with him in Alton today the

contract for the first house erected in Alton by contract. It was

the property of his father and his grandfather, Samuel Pluckard, was

the contractor.

Among those who attended the speaking were George C. Cockrell of

Omaha, who was one of the marshals of the parade fifty years ago,

and Hon. H. G. McPike, who was a member of the platform committee.

The only living speaker who took part in the program fifty years

ago, Joseph Sloss of Memphis, Tennessee, was unable to be here

because of his great age.

Mayor Beall wore a rosette that was worn by Daniel Sullivan's wife

in the celebration fifty years ago. It was loaned to the Mayor for

the day.

The exercises at the Airdome were opened at 2:30 o'clock. The

Amphitheatre was filled to its capacity and the east fence was taken

down to admit of the overflow standing in the street, hearing the

talk. After the prayer by Rev. R. P. Hammons, E. M. Bowman was

presented by Mayor Beall, and presided during the exercises. On the

stage were seated a large number of people who had heard the debate

of 50 years ago.

J. McCann Davis of Springfield was introduced for the first address.

He prefaced his remarks by referring to the late Stephen A. Douglas,

whose name was on the program, and who was to have delivered an

address. He paid a tribute to the memory of Mr. Douglas, and spoke

of a recent address of Mr. Douglas at Ottawa and Charleston. The

address of Mr. Davis was on the two giants of Illinois, Lincoln and

Douglas. Lincoln was little known, while Douglas was of national

reputation. Fifty years ago these two giants in Alton debated

momentous issues of the time. No two names in American history are

so inseparably linked as those of Lincoln and Douglas. If Lincoln

had not lived, the career of Douglas might have been the same. If

Douglas had not lived the world would not have known Lincoln as it

does today. Douglas' rise was rapid, at the age of 28 he being on

the Supreme Court bench. Lincoln was elected to Congress when

Douglas was the Senatorial compeer of Webster and Clay. Lincoln, in

a dingy law office at Springfield, sat downcast when Douglas was

being mentioned for the Presidency. Douglas for 28 years was the

master spirit of the majority party, while Lincoln was in the

weaker. In 1852 Lincoln was not even a delegate to the convention of

his party. It was supposed the slave question was settled. Both

parties had settled down to trivial issues, and Lincoln had his

beginning in 1854. Prior to that time, though rivals in many ways,

the two giants were personal friends and continued until death

separated them. In 1854 Douglas forced through Congress his

Kansas-Nebraska bill. He aroused from peaceful slumber Abraham

Lincoln. He became a changed man - his soul was stirred to the

depths. Slavery was a great institution of the country and its

solution baffled the minds of the greatest statesmen of the age.

Sooner or later the conflict had to be settled right. The effect of

the Kansas-Nebraska bill was to bring forth a new party and its

great leader. From that day Lincoln and Douglas opposed each other.

In the great debate of 1858, Lincoln found himself at a

disadvantage. The renown of his antagonist was world-wide. Of

himself Lincoln said nobody expects me to be president. Douglas won

the senatorial battle of 1858, but Lincoln had laid the foundation

of the defeat of his rival in 1860. In the crisis following

Lincoln's election, Douglas rose to the heights of statesmanship.

Douglas predicted a great war that would last for years. When

Lincoln was inaugurated, Douglas was at his side and offered him his

help. The great union speech of Douglas, delivered before the

Legislature at its next session, was said to be the greatest ever

delivered before the Legislature. Douglas was in a hard position. He

had a magnificent devoted following in the North. Defeat had come to

his party. If he had lapsed in the sullen silence of disappointment

the course of history would have been changed and the Confederacy

would have been maintained. He was not silent, and his words went

thundering over the country and stirred his followers to go forth to

do battle for their country. American history furnishes no higher

example of patriotism than that of Douglas in 1861. He died in the

noonday of life, his ambition unfulfilled and if Lincoln could speak

he would pay his tribute to his old antagonist.

Horace White of New York, who reported the Lincoln-Douglas debate,

as a newspaper reporter, was the next speaker. Mr. White was the

only person present at all the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858. He

heard the Lincoln speech in Springfield on the "House divided

against itself." He stated he remembered the Alton debate well.

Douglas' voice was so worn out his words could not be heard ten feet

from the platform. He had an air of entire confidence,

notwithstanding. Madison county was the pivot, being controlled by

the Whigs. Lincoln believed he could carry the Fillmore vote, but he

was mistaken, and Lincoln lost in this county. Lincoln's voice was

clear and high-pitched. He was perfectly at home. Lincoln is coming

into his kingdom with a completeness that no one could have

expected. Douglas brought Lincoln into the public eye and Lincoln

now keeps there.

Lyman Trumbull was one of the giants of 1858. His old home is still

in Alton. He made a great impression when he delivered his speech on

the Kansas-Nebraska bill. That measure, backed by Douglas, had

brow-beaten an almost terrorized foe. Before Trumbull appeared in

the Senate, Douglas had only one antagonist. Trumbull was a perfect

match for Douglas, and when he replied to Douglas the whole north

rang with his praises and said a great man had come forth to do a

great work. Lincoln's greatest mark was the emancipation

proclamation. Yet it had no real effect, as it applied only to

territory not under the President's control. It did not purport to

rest upon constitutional rights but only as a war measure. Public

opinion was divided. The questions that arose were puzzling. On

January 13th, 1864, a resolution was introduced in Congress to

abolish slavery, which became the 13th amendment. Illinois gave to

the union three great men - Grant, Lincoln and Trumbull. Trumbull,

the great senator who brought to the Senate the 13th amendment,

should be applauded by his fellow townsmen. Trumbull never sought a

personal controversy, but never declined one. His influence in the

Senate was great. Such was the Senator the citizens of Alton gave to

be the whole coadjutor of Lincoln and Grant.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN'S WORDS TO A LITTLE BOY

[By G. F. Long of Alton]

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, October 16, 1908

G. F. Long of 524 West Vine Street, Springfield, formerly of Alton,

is down taking in the Lincoln-Douglas celebration. He was present

fifty years ago at the debate between the two great men.

Incidentally, Frank was one of the most heroic Union soldiers who

shouldered a musket for his country. He is not very large

physically, but was made up of a brave spirit and did his duty at

the sacrifice of a limb, his hearing, and his eyesight. He was only

13 years old when he heard the great orators. What education he had

received was mostly gotten in the East where his father's home, the

late Dr. Long, was, and Douglas was the great man in that section,

Lincoln not being known there. Mr. Long and his father were on the

platform and Frank got as close to the future President as he could,

sitting on the railing. Sitting there he looked up into Lincoln's

face and mentally said, "he don't amount to much." Pretty soon

Lincoln began to warm up, his face glowed and the muscles of his

neck and throat swelled up as whip cords when some great idea struck

him, and the orator swung his arms out wildly, sometimes lurching

forward as he expressed his intense ideas. On one of those occasions

he came very near where the boy was sitting, and Frank moved to get

out of the way. Lincoln glanced down at Frank and said, "Never mind

little boy, I won't step on you." As one of "Father Abraham's"

soldiers a few years later, he was stepped upon quite severely by

mini rifle balls and bombs bursting in the air, in the wildest of

battle scenes in the South and in the last battle of Sherman's

campaign at Bentonville, North Carolina.

RECOLLECTIONS OF THE LINCOLN – DOUGLAS DEBATE

From “The Valley of Shadows, Recollections of the Lincoln Country,

1858 – 1863”

By Francis Grierson, 1909

My family and I lived in a large old house on the southern

outskirts, which had once been occupied by nuns who had a private

school there. It faced the great high-road, leading out into the

prairies, and we could see from the windows the wagons and buggies

arriving from the country far beyond. One day our attention was

attracted to the number of people coming down the hill in wagons and

on horseback, and while watching them, two figures that looked

familiar approached, jogging along on steeds that looked tired. The

men had about them something odd, almost fantastic. As they passed

the house, we recognized Azariah James and Elihu Gest. In less than

half an hour, along came Isaac Snedeker, then other familiar faces.

But what did it mean? All the old, outspoken Abolitionists from

up-country, with some of the Pro-Slavery people, were filing past.

When my father was asked what was the matter, he only said,

“Tomorrow is the great day!”

It was the 15th day of October 1858. Crowds were pouring into Alton.

For some days, people had been arriving by the steam packets from up

and down the river – the up-boats from St. Louis, bringing visitors

with long, black hair, goatees, and stolid, Indian-like faces,

slave-owners and slave-dealers, from the human marts of Missouri and

Kentucky. The northern visitors arriving by boat or rail,

Abolitionists and Republicans, with a cast of features distinctly

different from the types coming from the South.

They came from villages, townships, the prairies, from all the

adjoining counties, from across the Mississippi, from far-away

cities, from representative societies north and south, from

congressional committees in the east, from leading journals of all

political parties, and from every religious denomination within

hundreds of miles, filling the broad space in front of the town

hall, eager to see and hear the now-famous debaters – the popular

Stephen A. Douglas, United State Senator, nicknamed the “Little

Giant,” and plain Abraham Lincoln, nicknamed the “Rail-Splitter.”

The great debate had begun on the 21st of August at another town,

and today the long-discussed subject would be brought to a close.

Douglas stood for the doctrine that slavery was nationalized by the

Constitution, that Congress had no authority to prevent its

introduction in the new Territories like Kansas and Nebraska, and

that the people of each State could alone decide whether they should

be slave States or free. Lincoln opposed the introduction of slavery

into the new Territories.

On this memorable day, the “irrepressible conflict,” predicted by

Seward, actually began, and it was bruited about that Lincoln would

be mobbed or assassinated if he repeated here the words he used in

some of his speeches delivered in the northern part of the State.

From the surging sea of faces, thousands of anxious eyes gazed

upward at the group of politicians on the balcony, like wrecked

mariners scanning the horizon for the smallest sign of a white sail

of hope.

This final debate resembled a duel between two men-of-war, the pick

of a great fleet, all but these two sunk or abandoned in other

waters, facing each other in the open – the Little Giant hurling at

his opponent from his flagship of slavery, the deadliest missiles;

Lincoln calmly waiting to sink his antagonist by one simple

broadside. Alton had seen nothing so exciting since the

assassination of Lovejoy – the fearless Abolitionist - many years

before.

In the earlier discussions, Douglas seemed to have the advantage. A

past-master in tact and audacity, skilled in the art of rhetorical

skirmishing, he had no equal on the “stump,” while in the Senate, he

was feared by the most brilliant debaters for his ready wit and his

dashing eloquence.

Regarded in the light of historical experience, reasoned about in

the light of spiritual reality, and from the point of view that

nothing can happen by chance, it seems as if Lincoln and Douglas

were predestined to meet side by side in this discussion, and unless

I dwell in detail on the mental and physical contrast the speakers

presented, it would be impossible to give an adequate idea of the

startling difference in the two temperaments: Douglas – short,

plump, and petulant; Lincoln – long, gaunt, and self-possessed. The

one white-haired and florid; the other black-haired and swarthy. The

one educated and polished; the other unlettered and primitive.

Douglas had the assurance of a man of authority. Lincoln had moments

of deep mental depression, often bordering on melancholy, yet

controlled by a fixed, and I may say, predestined, will, for it can

no longer be doubted that without the marvelous blend of humor and

stolid patience so conspicuous in his character, Lincoln’s genius

would have turned to madness after the defeat of the Northern Army

at Bull Run, and the world would have had something like a

repetition of Napoleon’s fate after the burning of Moscow. Lincoln’s

humor was the balance-pole of his genius that enabled him to cross

the most giddy heights without losing his head.

Judge Douglas opened the debate in a sonorous voice, plainly heard

throughout the assembly, and with a look of mingled defiance and

confidence, he marshaled his facts and deduced his arguments. To the

vigor of his attack, there was added the prestige of the Senate

Chamber, and for some moments, it looked as if he would carry the

majority with him, a large portion of the crowd being Pro-Slavery

men, while many others were “on the fence,” waiting to be persuaded.

At last, after a great oratorical effort, he brought his speech to a

close, amidst the shouts and yells of thousands of admirers.

And now Abraham Lincoln, the man who, in 1830, undertook to split

for Mrs. Nancy Miller four hundred rails for every yard of brown

jean dyed with walnut bark, that would be required to make him a

pair of trousers. The flat boatman, local stump-speaker and country

lawyer, rose from his seat, stretched his long, boney limbs upward

as if to get them into working order, and stood like some solitary

pine on a lonely summit, very tall, very dark, very gaunt, and very

rugged – his swarthy features stamped with a sad serenity, and the

instant he began to speak, the ungainly mouth lost its heaviness,

the half-listless eyes attained a wondrous power, and the people

stood bewildered and breathless under the natural magic of the

strangest, most original personality known to the English-speaking

world since Robert Burns. There were other very tall and dark men in

the heterogeneous assembly, but not one who resembled the speaker.

Every movement of his long, muscular frame denoted inflexible

earnestness, and a something issued forth, elemental and mystical,

that told what the man had been, what he was, and what he would do

in the future. There were moments when he seemed all legs and feet,

and again he appeared all head and neck; yet every look of the

deep-set eyes, every movement of the prominent jaw, every wave of

the hard-gripping hand, produced an impression, and before he had

spoken twenty minutes, the conviction took possession of thousands

that here was the prophetic man of the present, and the political

savior of the future. Judges of human nature saw at a glance that a

man so ungainly, so natural, so earnest, and so forcible, had no

place in his mental economy for the thing called vanity.

Douglas had been theatrical and scholarly, but this tall, homely man

was creating by his very looks what the brilliant lawyer and

experienced Senator had failed to make people see and feel, The

Little Giant had assumed striking attitudes, played tricks with his

flowing white hair, mimicking the airs of authority with patronizing

allusions; but these affectations, usually so effective when he

addressed an audience alone, went for nothing when brought face to

face with realities. Lincoln had no genius for gesture and no desire

to produce a sensation. The failure of Senator Douglas to bring

conviction to critical minds was caused by three things: a lack of

logical sequence in argument, a lack of intuitional judgment, and a

vanity that was caused by too much intellect and too little heart.

Douglas had been arrogant and vehement, Lincoln was now logical and

penetrating. The Little Giant was a living picture of ostentatious

vanity; from every feature of Lincoln’s face there radiated the

calm, inherent strength that always accompanies power. He relied on

no props. With a pride sufficient to protect his mind and a will

sufficient to defend his body, he drank water when Douglas, with all

his wit and rhetoric, could begin or end nothing without stimulants.

Here, then, was one man out of all the millions who believed in

himself, who did not consult with others about what to say, who

never for a moment respected the opinion of men who preached a lie.

My old friend, Don Piatt, in his personal impressions of Lincoln,

whom he knew well and greatly esteemed, declares him to be the

homeliest man he ever saw, but serene confidence and self-poise can

never be ugly. What thrilled the people who stood before Abraham

Lincoln on that day was the sight of a being, who in all his actions

and habits, resembled themselves, gentle as he was strong, fearless

as he was honest, who towered above them all in that psychic

radiance that penetrates in some mysterious way every fiber of the

hearer’s consciousness.

The enthusiasm created by Douglas was wrought out of smart epigram

thrusts and a facile superficial eloquence. He was a match for the

politicians born within the confines of his own intellectual circle:

witty, brilliant, cunning, and shallow, his weight in the political

balance was purely materialistic; his scales of justice tipped to

the side of cotton, slavery, and popular passions, while the man who

faced him now brought to the assembly cold logic in place of wit,

frankness in place of cunning, reasoned will and judgment in place

of chicanery and sophistry. Lincoln’s presence infused into the

mixed and uncertain throng something spiritual and supernormal. His

looks, his words, his voice, his attitude were like a magical

essence dropped into the seething cauldron of politics, reacting

against the foam, calming the surface and letting the people see to

the bottom. It did not take him long.

“Is it not a false statesmanship,” Lincoln asked, “that undertakes

to build up a system of policy upon the basis of caring nothing

about the very thing that everybody does care the most about? Judge

Douglas may say he cares not whether slavery is voted up or down,

but he must have a choice between a right thing and a wrong thing.

He contends that whatever community wants slaves has a right to have

them. So they have, if it is not a wrong; but if it is a wrong, he

cannot say people have a right to do wrong. He says that upon the

score of equality, slaves should be allowed to go into a new

Territory like other property. This is strictly logical if there is

no difference between it and other property. If it and other

property are equal, his argument is entirely logical; but if you

insist that one is wrong and the other right, there is no use to

institute a comparison between right and wrong.”

This was the broadside. The great duel on the high seas of politics

was over. The Douglas ship of State Sovereignty was sinking. The

debate was a triumph that would send Lincoln to Washington as

President, in a little more than two years from that date.

People were fascinated by the gaunt figure, in long, loose garments,

that seemed like a “huge skeleton in clothes,” attracted by the

homely face, and mystified, yet proud of the fact that a simple

denizen of their own soil should wield so much power.

When Lincoln sat down, Douglas made one last feeble attempt at an

answer, but Lincoln, in reply to a spectator who manifested some

apprehension as to the outcome, rose, and spreading out his great

arms at full length, like a condor about to take wing, exclaimed,

with humorous indifference, “Oh! Let him go it!” These were the last

words he uttered in the greatest debate of the ante-bellum days.

The victor bundled up his papers and withdrew, the assembly

shouting, “Hurrah for Abe Lincoln as next President!” “Bully for old

Abe!” “Lincoln forever!” etc. Excited crowds followed him about,

reporters caught his slightest word, and by nighttime, the barrooms,

hotels, street corners, and prominent stores were filled with his

admirers, fairly intoxicated with the exciting triumph of the day.

NOTES:

Francis Grierson’s real name was Benjamin Henry Jesse Francis

Shephard. Born in England in 1848, he was a composer, pianist, and

writer, who used the pen name of Francis Grierson. His family

immigrated to Illinois in 1849, while he was yet a baby. They

settled in Sangamon County, where his father, Joseph, engaged in

farming. In 1858, before moving to St. Louis, the family lived in

Alton, where Benjamin was a witness to the Lincoln – Douglas debate.

Benjamin spent only ten years in Illinois before moving to St. Louis

with his family. His mother, Emily, found the Illinois prairies

lonesome and monotonous. In St. Louis, Benjamin served as a page on

the staff of General John C. Fremont. He then moved with his family

to Niagara Falls, and then to Chicago. He became a successful

composer and skillful pianist, and traveled in both Europe and

America.

OBITUARY OF LETITIA V. RUTHERFORD REVEALS STORY OF LOCAL SPEAKERS

AT LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATE

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, April 20, 1910

Mrs. Letitia V. Rutherford, a resident of Alton since 1858, died at

7:15 o'clock Wednesday morning, at her home, 431 east Ninth street,

after an illness of two weeks. Her death was due to a breaking down

of her system from old age, and had been expected for almost a week.

She was taken ill two weeks before her death with what was believed

to be a slight ailment, and she never was able to be around again.

Up to the evening before her death she was conscious, her mind was

undimmed, and while she knew for several days she was dying, she was

glad and ready to go and was happy with the members of her family

around her. Up to the time she lost consciousness finally, the

evening before her death, she conversed about current events, seemed

to be still as deeply interested in her friends and her family as

ever, and was not in the least perturbed by the certainty of her

near dissolution. Mrs. Rutherford had always maintained her youthful

interest in the young people. Her family and friends said she would

never grow old in spirit, because she loved children so well, and

this prediction was borne out to the last. She had a sweet

simplicity of soul that would not countenance any display, her

family and her friends were her little world, and she was never so

happy as when, surrounded by many of her descendants, she lay on her

dying bed. She was a devoted member of the Presbyterian church and

had held membership in the First Presbyterian church of Alton since

she came to this city. Her father was Rev. James Sloss, a

Presbyterian minister. She was born in Florence, Ala., and would

have been 79 years of age June 13. She was married on her 18th

birthday to Friend S. Rutherford, at her home, and she was separated

from him by death in June 1864. Her husband was the colonel of the

97th Illinois volunteers, and he was taken sick after a long

campaign in the neighborhood of Vicksburg, and at New Orleans. His

wife went south and brought him home, and soon thereafter she was

left with a large family of children, by her husband's death. She

always maintained her home circle, made it the center for the other

home circles that grew from her own, and was imbued with the spirit

of hospitality that made her home a delightful place to be. She

leaves four daughters, Mrs. W. C. Johnston of St. Louis; Miss Mary

Rutherford; Mrs. John F. McGinnis; Mrs. William Russell of Alton;

and one son, F. S. Rutherford of St. Louis. She leaves also an

adopted daughter, her niece, Miss Grace Sloss. She is survived by

two brothers, Joseph Sloss of Memphis, Tenn., and Robert Sloss. She

leaves thirty-six of grandchildren and eleven great-grandchildren.

In 1852 Mr. and Mrs. Rutherford and their 13 months' old daughter,

Anna, later Mrs. J. A. Cousley, now deceased, removed to

Edwardsville, where Mr. Rutherford began the practice of his

profession, the law. The family resided in Edwardsville until 1858,

until Mr. Rutherford received an appointment as one of the officials

of the Illinois State Penitentiary, then at Alton. Their residence

was continued here until the present time. Mrs. Rutherford's

brother, Joseph Sloss, is the only survivor of the persons who

participated in the original Lincoln-Douglas debate. Prior to the

arrival of the principal speakers it was planned that speeches would

be made by local talent. Her husband, F. S. Rutherford, and her

brother, Joseph Sloss, both attorneys, were the speakers selected to

represent the two parties, the brother being on the Douglas side and

her husband on the Lincoln side. Later both enlisted in armies, the

one to fight for the Union, the other for the Confederacy. Later her

brother was elected as representative in the United States congress,

and was later appointed U. S. Marshall for the North District of

Alabama of the Federal Court, by President Grant. The funeral will

be held Friday afternoon at 2:30 o'clock, and services will be held

in the First Presbyterian church by Rev. A. O. Lane. Burial will be

in City Cemetery.