Legend of the Piasa Bird

Return to Native American main page

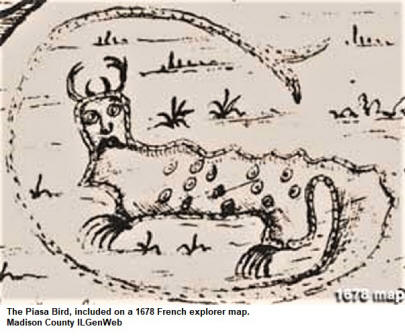

As Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, and Louis

Joliet, a fur trader, paddled down the Mississippi River near the

future site of Alton in 1673, they came across two large figures

painted on the side of the bluff. Marquette wrote in his journal:

“As we were descending the river, we saw high rocks with hideous

monsters painted on them, and upon which the bravest Indian dare not

look. They are as large as a calf, with head and horns like a goat,

their eyes are red, beard like a tiger’s and a face like a man’s.

Their tails are so long that they pass over their bodies and between

their legs under their bodies, ending like a fish’s tail. They are

painted red, green and black, and so well drawn that I could not

believe they were drawn by the Indians, and for what purpose they

were drawn seems to me a mystery.”

This

original description of the “hideous monsters” painted on the bluffs

did not include wings. The wings were added later in “The Piasa: An

Indian Tradition of Illinois,” written by Mr. John Russell of

Bluffdale, Illinois, c. 1836. Russell was a Baptist minister and

professor of Greek and Latin at Shurtleff College in Upper Alton,

and served as editor of a local paper called “The Family Magazine.”

The story of the Piasa Bird, although fiction, had an extensive

circulation. Russell took the name “Piasa” from the Piasa Creek

which ran through the main ravine in downtown Alton in its early

days. Piasa Creek has since been filled in and drainage pipes added,

and paved over to form Piasa Street. According to the story

published by Russell, the creature depicted by the painting on the

bluff was a huge bird that lived in the cliffs. Russell claimed that

this creature attacked and devoured people in nearby Native American

villages shortly after the corpses of a war gave it a taste for

human flesh. The legend claims that a local Indian chief, named

Chief Ouatoga, managed to slay the monster using a plan given to him

in a dream from the Great Spirit. The chief ordered his bravest

warriors to hide near the entrance of the Piasa Bird's cave, which

Russell also claimed to have explored. Ouatoga then acted as bait to

lure the creature out into the open. As the monster flew down toward

the Indian chief, his warriors slew it with a volley of poisoned

arrows. Russell claimed that the mural was painted by the Indians as

a commemoration of this heroic event. In the book “Records of

Ancient Races in the Mississippi Valley,” 1887, by William McAdams,

the author says he contacted John Russell, and Russell admitted the

story was “somewhat illustrated.” To Professor McAdams, the story

had little, if any, ethnological significance.

This

original description of the “hideous monsters” painted on the bluffs

did not include wings. The wings were added later in “The Piasa: An

Indian Tradition of Illinois,” written by Mr. John Russell of

Bluffdale, Illinois, c. 1836. Russell was a Baptist minister and

professor of Greek and Latin at Shurtleff College in Upper Alton,

and served as editor of a local paper called “The Family Magazine.”

The story of the Piasa Bird, although fiction, had an extensive

circulation. Russell took the name “Piasa” from the Piasa Creek

which ran through the main ravine in downtown Alton in its early

days. Piasa Creek has since been filled in and drainage pipes added,

and paved over to form Piasa Street. According to the story

published by Russell, the creature depicted by the painting on the

bluff was a huge bird that lived in the cliffs. Russell claimed that

this creature attacked and devoured people in nearby Native American

villages shortly after the corpses of a war gave it a taste for

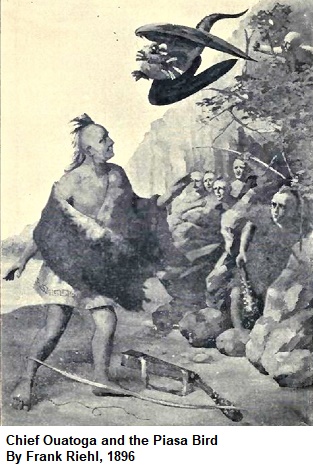

human flesh. The legend claims that a local Indian chief, named

Chief Ouatoga, managed to slay the monster using a plan given to him

in a dream from the Great Spirit. The chief ordered his bravest

warriors to hide near the entrance of the Piasa Bird's cave, which

Russell also claimed to have explored. Ouatoga then acted as bait to

lure the creature out into the open. As the monster flew down toward

the Indian chief, his warriors slew it with a volley of poisoned

arrows. Russell claimed that the mural was painted by the Indians as

a commemoration of this heroic event. In the book “Records of

Ancient Races in the Mississippi Valley,” 1887, by William McAdams,

the author says he contacted John Russell, and Russell admitted the

story was “somewhat illustrated.” To Professor McAdams, the story

had little, if any, ethnological significance.

To add to more confusion, John Russell published a different version

of the Piasa Bird legend in the October 28, 1847, Illinois Journal

of Springfield. In this version, the Piasa was a giant condor that

was slain by Alpeora, a courageous Indian who killed the monster

single-handedly. He returned to his original version of the legend

in the July 14, 1848 issue of the Evangelical Magazine and Gospel

Advocate. Written below is the original story of the Piasa Bird by

John Russell:

The Piasa: An Indian Tradition of Illinois, By John Russell

“No part of the United States, not even the highlands of the Hudson,

can vie, in wild and romantic scenery, with the bluffs of Illinois

on the Mississippi, between the mouths of the Missouri and Illinois

rivers. On one side of the river, often at the water’s edge, a

perpendicular wall of rock rises to the height of some hundred feet.

Generally, on the opposite shore is a level bottom or prairie of

several miles in extent, extending to a similar bluff that runs

parallel with the river. One of these ranges commences at Alton, and

extends for many miles along the left bank of the Mississippi. In

descending the river to Alton, the traveler will observe, between

that town and the mouth of the Illinois, a narrow ravine through

which a small stream discharges its waters into the Mississippi.

This stream is the Piasa. Its name is Indian, and signifies, in the

Illini, ‘The bird which devours men.’ Near the mouth of this stream,

on the smooth and perpendicular face of the bluff, at an elevation

which no human art can reach, is cut the figure of an enormous bird,

with its wings extended. The animal which the figure represents was

called by the Indians, ‘the Piasa.’ From this is derived the name of

the stream.

The tradition of the Piasa is still current among the tribes of the

Upper Mississippi, and those who have inhabited the valley of the

Illinois, and is briefly this:

Many thousand moons before the arrival of the pale faces, when the

great

Such was the state of affairs when Ouatoga, the great chief of the

Illini, whose fame extended beyond the Great Lakes, separating

himself from the rest of his tribe, fasted in solitude for the space

of a whole moon, and prayed to the great spirit, the Master of Life,

that he would protect his children from the Piasa.

On the last night of the fast, the Great Spirit appeared to Ouatoga

in a dream, and directed him to select twenty of his bravest

warriors, each armed with a bow and poisoned arrows, and conceal

them in a designated spot. Near the place of concealment, another

warrior was to stand in open view, as a victim for the Piasa, which

they must shoot the instant he pounced upon his prey.

When the chief awoke in the morning, he thanked the Great Spirit,

and returning to his tribe, told them his vision. The warriors were

quickly selected and placed in ambush as directed. Ouatoga offered

himself as the victim. He was willing to die for his people. Placing

himself in open view on the bluffs, he soon saw the Piasa perched on

the cliff, eying his prey. The chief drew up his manly form to his

utmost height, and planting his feet firmly upon the earth, he began

to chant the death-song of an Indian warrior. The moment after, the

Piasa arose into the air, and swift as the thunder-bolt, darted down

on his victim. Scarcely had the horrid creature reached his prey

before every bow was sprung and every arrow was sent quivering to

the feather into his body. The Piasa uttered a fearful scream, that

sounded far over the opposite side of the river, and expired.

Ouatoga was unharmed. Not an arrow, not even the talons of the bird

had touched him. The Master of Life, in admiration of Ouatoga’s

deed, had held over him an invisible shield.

There was the wildest rejoicing among the Illini, and the brave

chief was carried in triumph to the council house, where it was

solemnly agreed that, in memory of the great event in their nation’s

history, the image of the Piasa should be engraved on the bluff.

Such is the Indian tradition. Of course, I cannot vouch for its

truth. This much, however, is certain – that the figure of a huge

bird, cut in the solid rock, is still there, and at a height that is

perfectly inaccessible. How and for what purpose it was made I leave

it for others to determine. Even at this day an Indian never passes

the spot in his canoe without firing his gun at the figure of the

Piasa. The marks of the balls on the rock are almost innumerable.

Near the close of March of the present year (1836), I was induced to

visit the bluffs below the mouth of Illinois River, above that of

the Piasa. My curiosity was principally directed to the examination

of a cave, connected with the above tradition, as one of those to

which the bird had carried his human victims. Preceded by an

intelligent guide, who carried a spade, I set out on my excursion.

The cave was extremely difficult of access, and at one point in our

progress, I stood at an elevation of one hundred and fifty feet on

the perpendicular face of the bluff, with barely room to sustain one

foot. The unbroken wall towered above me, while below was the river.

After a long and perilous climb, we reached the cave, which was

about fifty feet above the surface of the river. By the aid of a

long pole placed on a projecting rock, and the upper end touching

the mouth of the cave, we succeed in entering it. Nothing could be

more impressive than the view from the entrance to the cavern. The

Mississippi was rolling in silent grandeur beneath us. High over our

heads a single cedar tree hung its branches over the cliff, and on

one of the dead, dry limb was seated a bald eagle. No other sign of

life was near us, a Sabbath stillness rested on the scene. Not a

cloud was visible on the heavens; not a breath of air was stirring.

The broad Mississippi was before us, calm and smooth as a lake. The

landscape presented the same wild aspect it did before it had met

the eye of the white man. The roof of the cavern was vaulted, and

the top was hardly less than twenty feet high. The shape of the

cavern was irregular, but so far as I could judge, the bottom would

average twenty by thirty feet. The floor of the cavern throughout

its whole extent was one mass of human bones. Skulls and other bones

were mingled in the utmost confusion. To what depth they extended I

was unable to decide, but we dug to the depth of 3 or 4 feet in

every part of the cavern, and still we found only bones. The remains

of thousands must have been deposited here. How and by whom, and for

what purpose, it impossible to conjecture.”

********

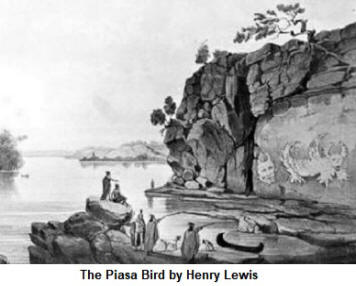

THE PAINTINGS ON THE BLUFF

The creatures painted on the bluffs near Alton were visible at least

until 1845. A few years later, the face of the bluff was gradually

quarried away for the purpose of making lime, and about the time of

the Civil War commenced, all traces of the ancient picture had

disappeared. In later years, the Piasa Bird, using the John Russell

story as a guide, was painted on the bluffs. This time wings were

added. This tradition has continued to this day.

According to Professor William McAdams, three or four miles above

Alton, below the mouth of the Piasa Creek (note that the Piasa Creek

that ran through Alton was called “Little Piasa,” and a larger Piasa

Creek exists further upriver from Alton), is a series of these old

pictographs, the most prominent of which are the outlines of two

huge birds without wings. They were painted or stained in the rock

with a reddish-brown pigment, and were situated on the bluff more

than one hundred feet above the river. On the top of the bluff above

these pictographs were a number of small ancient mounds. When

excavated, it was found that they contained human remains. These

drawings and mounds have long since faded away.

According to the History of Madison County, 1882,

painted on the bluff near Alton were two figures representing the

Good and the Evil Manitou (life force or Spirit). Large numbers of

Indians visited the site frequently to worship, shooting their

arrows or guns at the Evil Manitou.

IN SUMMARY

I believe the Piasa Bird, as we know it today, was a symbol of the

Evil Manitou – an evil spirit that brought hardships to the tribe,

such as drought, war, and sickness. Shooting their arrows or guns at

the Evil Manitou was to show their bravery, and ward off any

troubles it may try to bring. According to Father Marquette, he and

Joliet were warned before their long journey down the Mississippi of

a Manitou, or Spirit, which they could not pass. As further evidence

of the meaning of the painting on the bluffs, Mrs. Mary M. Bostwick

of Alton recalled how the Indians, coming down the Mississippi in

their canoes, shot at the painted monster on the bluffs with their

arrows. She stated they did not regard it as a bird, but rather as a

Devil and enemy of the tribe.

In summary, although many have referred to the John Russell fiction

story as truth, it is not. There is no basis on which to try and

determine whether or not the Piasa Bird actually lived in

pre-historic times, since it was not real. The Piasa Bird was a

symbol to the Native Americans – a symbol of a spiritual force that

they believed could bring good or evil to their communities.