Wood River Massacre

Return to Native American main page

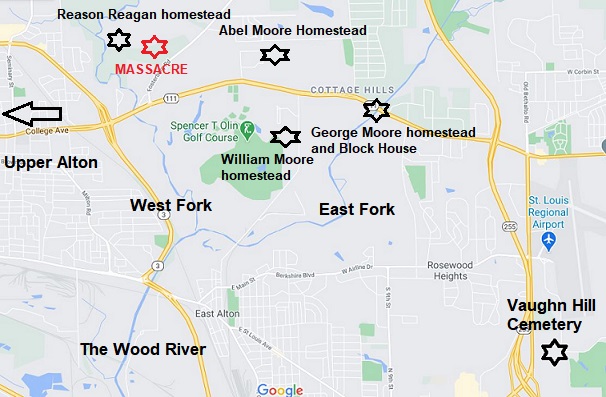

The most shocking and cruel atrocity committed within the bounds

of Madison County was the Wood River Massacre, on July 10, 1814,

that resulted in the death of one pregnant woman and six children. This

tragedy took place in the forks of the Wood River, east of Upper

Alton. The victims were the wife and two children of Reason Reagan,

two children of Abel Moore, and two children of William Moore.

At the beginning of the War of 1812-14, citizens of Madison County

who lived at exposed locations on the frontier sought refuge in the

forts and blockhouses. When no Native Americans made their

appearance, and the Rangers were constantly on the alert, people

began to feel secure. In the summer of 1814, they returned to their

farms and dwellings. There were six or eight families residing at

that time in the forks of the Wood River. At the residence of George

Moore on the east branch of the Wood River, a blockhouse had been

built to which the people could flee should danger arrive.

July

10, 1814, began as a pleasant Sunday. William Moore was on duty at

Fort Butler near St. Jacob; his brother, Abel Moore had gone to Fort Russell near

Edwardsville for the day; and Reason Reagan had gone three miles

away to the Wood River Baptist Church on Vaughn Hill in Wood River

Township. Rachel Reagan and her two children spent the day with her

sister, Mrs. William Moore. Also at the Moore home was Miss Hannah

Bates, sister of Abel Moore’s wife, Mary Bates Moore. The time was spent peacefully

while the women talked and the children played games. Later in the

afternoon they all went to the Abel Moore home, located near where

the Alton State Hospital was later constructed on Rt. 140. As

preparation began for the evening meal, Rachel Reagan, who was in

advanced stage of pregnancy, decided she would go back home and pick

some beans that would be added to the evening mean. Rachel’s two

children, two sons of William Moore, and two sons of Abel Moore

accompanied her. Hannah Bates went along, but for some reason

decided to turn back to the Moore house. Some say she had a

premonition. Others say her shoes did not fit well and hurt her

feet. Regardless, that decision saved her life.

July

10, 1814, began as a pleasant Sunday. William Moore was on duty at

Fort Butler near St. Jacob; his brother, Abel Moore had gone to Fort Russell near

Edwardsville for the day; and Reason Reagan had gone three miles

away to the Wood River Baptist Church on Vaughn Hill in Wood River

Township. Rachel Reagan and her two children spent the day with her

sister, Mrs. William Moore. Also at the Moore home was Miss Hannah

Bates, sister of Abel Moore’s wife, Mary Bates Moore. The time was spent peacefully

while the women talked and the children played games. Later in the

afternoon they all went to the Abel Moore home, located near where

the Alton State Hospital was later constructed on Rt. 140. As

preparation began for the evening meal, Rachel Reagan, who was in

advanced stage of pregnancy, decided she would go back home and pick

some beans that would be added to the evening mean. Rachel’s two

children, two sons of William Moore, and two sons of Abel Moore

accompanied her. Hannah Bates went along, but for some reason

decided to turn back to the Moore house. Some say she had a

premonition. Others say her shoes did not fit well and hurt her

feet. Regardless, that decision saved her life.

Two days before, Reason Reagan and his brother-in-law, Samuel

Thomas, had gone to a deer lick [spot of ground where deer gather,

due to natural salt in the ground] about ten miles west of the

settlement [this would have placed the deer lick in Jersey County,

north of Lockhaven], and camped there for the night. It was later

ascertained that a company of eleven Indians had been three miles

distant [near Dow], and the next morning found the abandoned camp of

Thomas and Reagan. The Indians determined the group was a small one,

and decided to follow their tracks eastward.

The Indians may have reached the empty Reagan cabin first, but no

one was at home. They continued on the trail eastward, toward Abel

Moore’s home, as Rachel and the children approached from the east.

It was on this trail that Rachel and the children met their untimely

death. They were stripped of their clothing, bludgeoned with a

tomahawk, and scalped.

William Moore, having returned that day to look after the women and

children at home, became alarmed as night approached and the

children had not returned. He first went to his brother, Abel

Moore’s place, to see if they were there. His wife, who was Mrs.

Reagan’s sister, also started on horseback to look for them, taking

a different route from her husband. Mrs. Moore chose to go through

the woods, and William walked along the wagon path. Mrs. Moore found

the children lying by the road, and at first thought they had laid

down to sleep. It was nighttime, and there was little light to see

by. She called their names, but they did not answer. She dismounted

her horse, and discovered the lifeless bodies in the darkness. She

placed her hand on the shoulder of the naked corpse of Mrs. Reagan.

On further examination, she could feel the flesh from which the

scalp had been torn. Hearing a noise, she became alarmed. She

quickly mounted her horse and rode away, thinking she would be the

next victim. Once at home, she put a large kettle of water of the

fire, thinking she would defend herself with boiling water.

Unknown to Mrs. Moore, her husband, William, had also found the

bodies. He had returned to Abel Moore’s home, telling that someone

had been killed by Indians. He could not see in the dark who it was.

Thinking the Indians were having an uprising, he wanted to warn the

others and get them to safety. From Abel’s house he took Abel’s wife

and her remaining children, along with Hannah Bates, and they headed

to William Moore’s house, with the plan of going on to the

blockhouse at Fort Wood River, near George Moore's homestead, where

they would be safer. Approaching his home, he saw the horse which

his wife had ridden. “Thank God, Polly is not killed,” he said. His

wife came running out, exclaiming, “They are killed by the Indians,

I expect!” The whole party then departed for the blockhouse, and

waited for daybreak.

At dawn a search party went out to look retrieve the bodies of

Rachel and the six children. They were shocked to find Timothy

Reagan sitting near the body of his mother still alive, but barely.

Pathetically he said, “The black man raised his axe and cutted them

again.” Timothy was taken up and given all the help they could give.

He died later that day. Others gathered the bodies of the dead.

Solomon Preuitt assisted by hauling them on a small, one-horse sled

to the burying ground on Vaughn Hill, about four miles “as the crow

flies” from Abel Moore’s home. This burial ground was established by

the Wood River Baptist Church, where Reason Reagan was at the time

of the massacre. The graves were dug and lined with slabs split from

nearby trees, and the bodies were lowered in and covered with more

planks. The seven were buried in three graves: Mrs. Reagan and her

two children, Elizabeth and Timothy, in one grave; Captain Moore’s

children, William and Joel, in another; and William Moore’s two

children, John and George, in the third. A stone slab was placed on

their grave at a later day, when peace had returned to the

settlement. Also buried in the Vaughn Hill Cemetery is an Indian girl who was

captured by Abraham Preuitt during one of the campaigns in the War

of 1812. Preuitt, pursuing Indians into the Winnebago Swamps, heard

firing in the distance and went to investigate. He found Davis

Carter and another man firing at a little Native American child, six years

old, who was mired and could not get out. He called the man cowards,

and ordered them to cease firing at a helpless child. Preuitt went

into the swamp and rescued the child, and brought it home with him.

She lived to the age of fifteen. It was stated that she was always

of a wild nature.

A young man by the name of John Harris, living at Able Moore’s home,

set off on horseback bearing the alarming news of the massacre to

Fort Russell. Leaving the Fort about 1:00 a.m., seventy rangers

arrived at Abel Moore’s about sunrise, and proceeded to the scene of

the tragedy. News soon spread, and it was not long before Captain

Whiteside and nine others gave pursuit of the Native Americans.

Among them were James Pruett, Abraham Pruett, William and John

Sample, James Starkden, William Montgomery, and Peter Waggoner. When

the Natives learned they were being pursued, the frequently bled

themselves to facilitate their speed and give them greater

endurance. The weather was hot, and some of the rangers’ horses gave

out. Others kept going. On the evening of the second day, between

sunset and dark, they came within sight of the Natives at a stream

entering the Sangamon River, about 70 miles in Morgan County. This

site was later named Indian Creek to remember what took place there.

On the ridge was a lone cottonwood tree. Several Natives climbed the

tree and saw their pursuers. They separated and went in different

directions. James and Abraham Pruett, taking the trail of one of

them, overtook him and shot him in the thigh. He fell, but managed

to climb a tree. Abraham then shot again and killed him. In the

Native American’s pouch was the scalp of Mrs. Reagan. The remaining

Natives hid in the woods, near where Virden now stands, about 44

miles north of the scene of the murder. It was learned later that

only one Native escaped, and that was the Chief who led the party.

On September 11, 1910, over 1,000 spectators gathered on the John

Moore farm to witness the unveiling of the monument erected by the

grandchildren of Captain Abel Moore, in memory of the victims of the

Wood River Massacre. Frank Moore of Chicago (youngest son of Major

Franklin Moore and grandson of Captain Abel Moore) presided and gave

the opening address of welcome. The monument was unveiled by Harriet

Moore of Wichita Falls, Texas, during an address by Edith Culp, wife

of John S. Culp. Addresses followed by Hon. N. G. Flagg of Moro, and

Major E. K. Pruett of Fosterburg. The grandchildren of Captain Abel

Moore who erected the monument were: Dr. Isaac Moore of Alton; John

Moore of Wichita Falls, Texas; Frank Moore of Chicago; Irby, Joel

and Luella Williams; and Mrs. Edith Culp of Wood River Township;

Thomas Hamilton of Buffalo, Wyoming; Mrs. Mary J. Deck of Roodhouse;

Lewis Moore of Granite City; and Mrs. Mary Moore of Seattle,

Washington.The monument is located on Fosterburg Road, in front of

the Hilltop Auction and Banquet Center. The massacre took place 300

yards behind the monument, and about one mile from the Abel Moore

home.

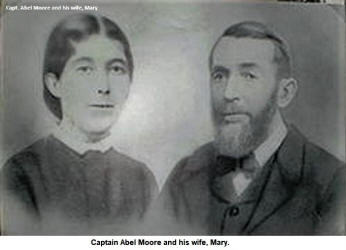

On September 14, 1980, the Bushrod’s Raiders historical preservation

group erected a new monument on the former Abel Moore homestead,

across from the main entrance to Gordon F. Moore Park. It is near a

small plot containing the graves of Abel Moore and his wife, Mary.

The monument was made of limestone from a 100-year-old wall, taken

from St. Joseph Hospital property when a new addition was

constructed. The monument contains a granite plaque telling the

story of the massacre.

THE WOOD RIVER MASSACRE

Read before the Illinois State Lyceum, December 6, 1833

By Rev. Thomas Lippincott

Source: Alton Telegraph, April 04, 1873

Travelers who have passed on the direct road from Edwardsville to

Carrollton (which is north of Jerseyville) will remember at a

pleasant plantation on the banks of the east branch of the Wood

River, a short distance from the dwelling house and powder mill of

Mr. George Moore, an old building, composed of rough round logs, the

upper story of which projects about a foot on every side beyond the

basement [the east fork of the Wood River is located just east of

Stanley Road, near Cottage Hills). This, in times of peril, was a

blockhouse, or in the common phrase, a fort, to which the early

settlers resorted for safety. Pursuing the road about two miles to

an elevated point of the west fork (near Fosterburg Road), where the

road turns abruptly down into the creek, another farm, now in

possession of a younger member of the family of Moores [Major Frank

Moore property], exhibits the former residence of Reason Reagan, and

midway between these two points resides Captain Abel Moore, on the

same spot which he occupied at the period to which our narrative

relates. William Moore lived nearly south of Abel’s, on a road which

passes towards Milton. Upper Alton is from two to three miles, and

Lower Alton four or five miles distant from the scene of action.

It appears that while the gallant rangers were scouring the country,

ever on the alert, the inhabitants, who for several years had

huddled together in forts for fear of Indians, had, in the summer of

1814, attained to such a sense of security that they went to their

farms and dwellings, with the hope of escaping further depredations.

In the forks of the Wood River were some six or eight families,

whose men were for the most part in the ranging service, and whose

women and children were thus left to labor and defend themselves.

The blockhouse which I have described was their place of resort on

any alarm, but the inconvenience and difficulty of clustering so

thickly induced them to leave it as soon as prudence would at all

permit.

Nor had the hardy inhabitants forgotten amidst their dangers, the

duties of social life, nor their highest obligations to their

Creator. The Sabbath shone, not only upon the domestic circle, as

gathered around the fireside altar, but its hallowed light was shed

on groups collected in the rustic artifices which the piety of the

people had erected for divine worship.

It was on the Sabbath, July 10, 1814, that the painful occurrence

took place which I now record. Reagan had gone to attend divine

worship at the meeting house some two or three miles off, leaving

his wife and two children at the house of Abel Moore, which was on

his way. About four o’clock in the afternoon, Mrs. Reagan went over

to her own dwelling to procure some little articles of convenience,

being accompanied by six children, two of whom were her own; two

were children of Abel Moore; and two of William Moore. Not far from,

probably a little after the same time, two men of the neighborhood

passed separately, I believe, along the road, in the opposite

direction to that in which Mrs. Reagan went, and one of them heard

at a certain place a low call, as of a boy, which he did not answer,

and for a repetition of which he did not delay. But he remembered

and told it afterwards.

When it began to grow dark, the families became uneasy at the

protracted absence of their respective members, and William Moore

came to Abel’s, and not finding them there, passed on towards Mr.

Reagan’s to discover what had become of the sister-in-law and

children. Nearly about the same time, his wife went across the angle

directly toward the same place. Mr. Moore had not been long absent

from his brother’s, before he returned with the information that

someone was killed by the Indians. He had discerned the body of a

person lying on the ground, but whether man or woman, it was too

dark for him to see without a closer inspection than was deemed

safe. The habits of the Indians were too well known by these

settlers, to leave a man in Mr. Moore’s situation, free from the

apprehension of an ambuscade still near.

The first thought that occurred was to flee to the blockhouse. Mr.

Moore desired his brother’s family to go directly to the fort, while

he should pass by his own house and take his family with him. But

the night was now dark, and the heavy forest was at that time

scarcely opened here and there by a little farm, while the narrow

road wound through among the tall trees, from the farm of Abel Moore

to that of his brother, George Moore, where the fort was erected.

The women and children, therefore, chose to accompany William Moore,

though the distance was nearly doubled by the measure.

The feelings of the group as they groped their way through the dark

woods may be mor easily imagined than described. Sorrow for the

supposed loss of relatives and children was mingled with horror at

the manner of their death, fear for their own safety, and pain at

the dreadful idea that remains of their dearest friends lay mangled

on the cold ground near them, while they were denied the privilege

of seeing and preparing them for sepulture.

Silently they passed on till they came to the dwelling of William

Moore, and when they had approached the entrance, he exclaimed, as

if relieved from some dreadful apprehension, “Thank God, Polly is

not killed.” “How do you know?” they inquired. “Because here is the

horse she rode.” My informant then first learned that his

brother-in-law had feared, until that moment, that his wife was the

victim that he had discovered.

As they let down the bars, Mrs. William Moore came running out,

exclaiming, “They are killed by the Indians, I expect.” The mourning

friends went in for a short time, but hastily departed for the

blockhouse, whither by daybreak, all or nearly all the neighbors,

having been warned by signals, repaired to sympathize and tremble.

I have mentioned that Mrs. William Moore went, as well as her

husband, in search of her sister and children. Passing by different

routes, they did not meet on the way, nor at the place of death. She

jumped on a horse and hastily went in the nearest direction, and as

she went, carefully noted every discernable object, until at length,

she saw a human figure lying near a burning log. There was not

sufficient light for her to discern the size, sex, or condition of

the person, and she called the name of one and another of her

children, again and again, supposing it to be one of them asleep. At

length, she alighted, and approached to examine more closely. What

must have been her sensations on placing her hand upon the back of a

naked corpse, and feeling, by further scrutiny, the quivering flesh

from which the scalp had been torn! In the gloom of the night, she

could just discern something, seeming like a little child, sitting

so near the body as to lean its head, first one side, then the

other, on the insensible and mangled body. She saw no further, but

thrilled with horror and alarm, remounted her horse and hastened

home. When she arrived, she quickly put a large kettle of water over

the fire, intending to defend herself with scalding water, in case

of an attack.

There was little rest or refreshment, as may well be supposed, at

the fort that night. The women and children of the vicinity,

together with the few men who were at home, were crowded together,

not knowing but that a large body of the savage foe might be

prowling round, ready to pour a deadly fire upon them at any moment.

A neighbor and six children of the little settlement were probably

lying in the wood, within a mile or two, dead and mangled by that

dreadful enemy! About three o’clock, a messenger was dispatched to

Fort Russell with the tidings.

In the morning, the inhabitants undertook the painful task of

ascertaining the extent of their calamity, and collecting the

remains for burial. The whole party, Mrs. Reagan and the six

children, were found lying at intervals along the road, tomahawked,

scalped and dead, except the youngest of Mrs. Reagan’s children,

which was sitting near its mother’s corpse, alive, with a gash,

large and deep, on each side of its little face. It were idle to

speak of the emotions that filled the souls of the neighbors and

friends and fathers and mothers, the husband, who had gathered round

to behold this awful spectacle. There lay the mortal remains of six

of those whom but yesterday they had seen and embraced in health,

and there was one helpless little one, wounded and bleeding and

dying, an object of pain and solicitude, but scarcely of hope.

To women and youth, chiefly was committed the painful task of

depositing their dear remains in the tomb. This was done on the six

already dead, on that day. They were interred in three graves, which

were carefully dug so as to lay boards beneath, beside, and above

the bodies – for there could no coffins be provided in the absence

of nearly all the men – and the graves being filled, they were left

to receive in aftertimes, when peace had visited the settlement, a

simple covering of stone, bearing an inscription descriptive of

their death.

It was a solemn day, observed my informant, to follow several bodies

to the grave, at once, from so small a settlement, and they too,

buried under such painful circumstances. Could we have followed that

train to the cemetery where they were embowered, would we not feel

that the procession, the occasion, the ceremony, the emotions were

of a character too awful, too sacred to admit of minute observation

then – or accurate description now? The seventh, however, was not

then buried. The child found alive received every possible

attention. Medical aid was procured with great difficulty, but in

vain. It followed within a day or two at most.

On the arrival of the messenger at Fort Russell, a fresh express was

hastened to Captain (now General) Samuel Whiteside’s company, which

was on Ridge Prairie, some four miles east of Edwardsville. It was

about an hour after sunrise on Monday morning when the gallant troop

arrived on the spot – having rode some fifteen miles – ready to weep

with the bereaved, and to avenge them of their ruthless foes. Abel

Moore, who was one of the rangers then on duty, and of course absent

at the catastrophe, was permitted to remain at home to assist in

burying his children and relatives, and the company dashed on, eager

to overtake and engage in deadly conflict with the savages. I regret

that I have no recent account of the particulars of this interesting

pursuit, and that my memory does not hold them with sufficient

distinctness to warrant an attempt at the narration. At Indian

Creek, in what is now Morgan County, some three or four of the

Indians were seen, and one killed. It is a current report among the

rangers that not one of the ten that composed the party survived the

fatigue of the retreat before the eager troop.

WILL ERECT A MONUMENT FOR VICTIMS OF THE WOOD RIVER MASSACRE

Source: Alton Telegraph, May 28, 1896

It was on July 10, 1814, that the Indians committed their most cruel

atrocity in Madison County, an atrocity that aroused the whole

country. One wife and mother, and six children, members of the

Reason Reagan, Abel Moore, and William Moore families were the

victims, and it is to their memories that a handsome monument is to

be erected on the site of the tragedy, which is between the forks of

the Wood River, something over two miles east of Upper Alton, by

Major Franklin Moore and his sister, who are the only persons now

living – so far as known – who lived then, and whose immediate

family furnish four of the victims. The Major says he is getting

old, and that he and his sister have concluded to go about this work

at once, in order that future generations may know and appreciate

the hardships and heartaches the pioneers suffered in paving the

path of civilization.

WOOD RIVER MASSACRE

By Volney P. Richmond

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, 1899

(After Consultation with Descendants of Moore Family)

“Since my earliest recollection I have heard and read of the Wood

River Massacre, and have often had the place pointed out to me where

it occurred, and my first acquaintance was with Captain Abel Moore

and his brother, and with several of Captain Moore’s children. Major

Frank Moore [son of Captain Abel Moore] cannot tell when he did not

know me. I used to often stop and hear pioneer stories from his

father. I knew, but was not intimately acquainted with, the others.

Some years ago, someone published an account of the Wood River

Massacre, and so far from correct, that I answered it and told what

I knew. By that paper the scene was laid near where the two railways

and wagon road bridges crosses Wood River at a place called Milton,

some two miles or more from where I knew it to have taken place. Not

long after I met Major Moore, and after thanking me for making the

correction, said that I was nearer to it than anyone who had written

before me, but that I was still somewhat off. I said to him I would

try again, and with his help and his sister’s, Mrs. Lydia Williams,

I though I could get a correct history. There has been nothing

heretofore written (not even my own) that is perfectly reliable, and

this being a part of the early history of Madison County, and an

Indian massacre of the War of 1812 to 1815 should be. Of course,

there is no one who could personally vouch for the truth, but the

children of Captain Abel Moore would be the nearest to the mark.

They have often heard the story from father and mother, and I, too,

have heard it from their father.

The Wood River Massacre of the township of Wood River, and county of

Madison, and State of Illinois, took place on July 10, 1814, in the

southeast quarter of section 5 of Wood River Township. The parties

massacred were Mrs. Rachel Reagan and her two children - Elizabeth

(Bessey), aged 7 years, and Timothey, aged 3 years; two children of

Captain Abel Moore’s – William, aged 10, and Joel, aged 8 years; and

two children of William Moore’s, John, aged 10, and George, aged 3

years. The party started from the house

of Reason Reagan to spend the day at William Moore’s, the farm now

owned by Mrs. William Badley. Returning in the afternoon by way of

Abel Moore’s farm, now owned by George Cartwright, two of whose

children, William and Joel, started home with them to get some green

beans. Miss Hannah Bates, Mrs. Abel Moore’s sister, visiting there,

also started with them to remain at Mrs. Reagan’s, but after going a

part way, suddenly changed her mind, as if warned by some

presentment, and against the earnest entreaties of Mrs. Reagan,

retraced her steps and hastened back home. From where she turned

back, she could not have been more than two or three hundred yards

from where the body of Mrs. Reagan was found. Mrs. Reagan and the

children were all tomahawked and scalped, and they remained on the

ground where they fell all night, the Indians having stripped them

of all their clothing.

William Moore, having returned that day from Fort Butler, near the

site of the village of St. Jacob, to look after the women and

children at home, became alarmed as night approached, the children

not returning, and went in search of them, going by Abel Moore’s.

Mrs. William Moore, who was a sister of Mrs. Reagan’s, also went on

horseback, going a different route from that her husband had taken.

Although they did not meet until after they had returned home, they

both found the lifeless bodies in the darkness lying by the wayside,

and each placed a hand upon the bare shoulder of Mrs. Reagen. Mr.

Moore returned by way of Abel Moore’s to notify them and prepare for

what might come to pass. At first, Mrs. William Moore thought the

children being tired, had fallen asleep and stooped to pick up the

youngest child, but as she did so, a crackle and a sudden flash of

light from a burning hickory tree nearby prevented her. Thinking it

was the Indians in ambush, she sprung upon her horse, and reached

home before her husband. Mrs. Reagan and her two children were

killed nearest to the place from where they started on their return.

The others were lying farther on, two at a place. One, the youngest

child, three years of age, was living when found. A message was sent

to Waterloo for the nearest physician, who dressed the wounds of the

little one, but it did not survive the operation.

A young man named John Harris, living at Abel Moore’s, was sent that

night on horseback to Fort Russell, located in the township of that

name, Captain Moore commanding, and to Fort butler, Captain

Whitesides commanding, to give the alarm. Leaving the latter place

about one o’clock the same night, about seventy of the rangers from

both forts, among whom were James and Solomon Preuitt, and arrived

at Moore’s fort on the farm owned by the late William Gill, now by a

German named Klopmeyer, about sunrise, and proceeded to the scene of

the tragedy. They were enabled to follow the track of the broken

limbs on the bushes, which the Indians did, as was supposed, to

tantalize the helpless women, thinking there were no men near enough

to pursue them, and further on by the way, they made through the

tall prairie grass, and also by blood. The Indians, when they

learned they were pursued, frequently bled themselves to facilitate

their speed and give them greater endurance. In hot pursuit, the

Rangers pressed upon the fleeing Red Men, overtaking them between

sunset and dark at a small stream near Sangamon River, about seventy

miles distant in Morgan County, named Indian Creek in honor of the

event. One was shot and killed in the top of a fallen tree. A bullet

from the rifle of James Preuitt stopped with him. The other nine

(there being ten in number) died from exhaustion, except one who

survived, and escaping reached camp, and afterward reported the

facts at the New Orleans Treaty, 1815. Dark overtaking the Rangers,

they camped at the creek and returned home the following morning.

The morning after the massacre, the relatives and friends prepared

to bury their dead, and this was no small undertaking. There was

nothing like any sawed lumber in the whole country. They had very

few tools, other than rakes and hoes. They decided to bury them

where a few of the first settlers had been buried sometime before,

and the first burying ground in this part of the county east from

their homes [Vaughn Hill Cemetery]. The only way to move them was by

oxen and rough-made sleds. The graves being dug, there was a vault

sunk at the bottom, the shape of a coffin and lines with slabs split

from the trees nearby, and as near as possible to the form of

planks, and the vaults lined with them and covered with the same.

They were buried in three graves – Mrs. Reagan and her children in

one; Captain Moore’s two children in another; and William Moore’s

two children in the third.

When I was first at this graveyard, there was a heavy growth of

timber, and an old church, built by setting posts in the ground and

siding up with rough-split boards, and covered with the same.

“Moore’s Settlement,” in the forks of the Wood River, was begun in

1804 by George, William, and Abel Moore, William Bates, Ransom

Reagan, Mr. Wright, Samuel Williams, Mr. Vickery, and some others

and their families. On George Moore’s farm was a fort, where the

residents used to assemble when there appeared to be danger from

Indian raids. At the time of the messacre, but one man remained at

the fort. That was George Moore, a gunsmith, who made and repaired

rifles for the Rangers and neighbors. Of these who took refuge in

the fort that night, there is probably but one now living – Mrs.

Nancy Hedden, a daughter of Captain Abel Moore. She resides at San

Diego, California, and was then about a year and a half old.

Such is the true history of the Wood River Massacre, 1814. I have

taken much time to trace out all necessary facts, and I believe the

foregoing to be perfectly true. I have been on the grounds and

passed in sight many times. I have been well acquainted with many of

the families all my days, and am interested in a true statement.

Signed, Volney P. Richmond.”

MONUMENT TO THE WOOD RIVER MASSACRE VICTIMS

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, September 15, 1899

A monument to the memory of the victims of the famous Wood River

Massacre will be erected in the Vaughn Cemetery, two miles south of

Bethalto, next week, by Major Franklin Moore and his sister, Mrs.

Lydia Williams. The seven victims of the Indians were buried in the

cemetery, and in the vicinity of the place where they are buried the

stone will be raised. The victims of the massacre were the wife and

two children of Reason Reagan; two children of Abel Moore; and two

children of William Moore. The massacre occurred on Sunday morning,

July 10, 1814, in the forks of the Wood River, about three miles

east of the present site of Upper Alton. The country there was

settled by the Moore family, and Abel Moore was the father of Major

Moore and Mrs. Williams. The history of the massacre is familiar to

everyone in this vicinity. While the fathers were away from home

attending church, the savages swarmed from the timber and murdered

all the defenseless children with Mrs. Reagan. It is said another

monument will be erected soon at the scene of the massacre, beside

the Fosterburg Road, and less than thirty rods from the very spot

where the murders occurred.

WOOD

RIVER MASSACRE MONUMENT

WOOD

RIVER MASSACRE MONUMENT

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, Sept. 12, 1910

The dedication of the Wood River Massacre memorial monument on

Fosterburg Road, east of Upper Alton, on the afternoon of September

11, 1910, drew an immense crowd. It was a quiet, reverential crowd

that assembled, and notwithstanding the fact that the sun was

beaming down with its rays uninterfered with by any covering, an

immense crowd waited patiently for an hour after the starting time

for the program to begin. J. Nic Perrin of Belleville, a principal

speaker, failed to arrive on time, but one there, the program was

under way.

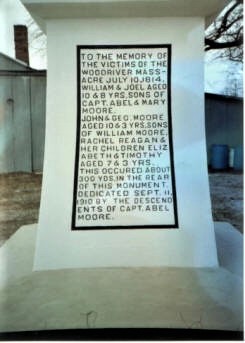

The monument, paid for by the grandchildren of Abel Moore, was

constructed by a Methodist preacher from Wichita Falls, Texas, who

was taking his vacation and came here to help raise money for his

church. He claimed to be an expert concrete worker, and he took the

job. The monument is 20 feet high, and has a 9-foot base. On one

face of the tower is the inscription:

“To the memory of the victims of the Wood River Massacre, July 10,

1814. William and Joel, 10 and 8 years, sons of Captain Abel and Mary

Moore; John and George, 10 and 3 years, sons of William Moore;

Rachel Reagan, and Elizabeth and Timothy, 7 and 3 years. This

occurred about 300 yards in the rear of this monument. Dedicated

September 11, 1910, by the descendants of Captain Abel Moore.”

William and Joel, 10 and 8 years, sons of Captain Abel and Mary

Moore; John and George, 10 and 3 years, sons of William Moore;

Rachel Reagan, and Elizabeth and Timothy, 7 and 3 years. This

occurred about 300 yards in the rear of this monument. Dedicated

September 11, 1910, by the descendants of Captain Abel Moore.”

Frank E. Moore of Chicago, a newspaper man, served as chairman for

the program. A quartet consisting of Jay Dodge, Alan Atchison, Fidel

Deem, and Joel Williams, sang several numbers, opening with

“America.” Rev. T. N. Marsh offered the invocation, followed by the

opening remarks by Frank E. Moore. The quartet sang “The Sword of

Bunker Hill.” The unveiling recitation, given by Miss Edith Culp,

was a brief historical account of the incident that was being

commemorated, and at the close of her address, the string was pulled

by Miss Hazel Moore of Wichita Falls, Texas, and the monument was

unveiled. Miss Edith Culp then formally made the presentation of the

monument to the county, and it was accepted by John U. Uzzell. The

quartet then sang “Illinois.”

Norman G. Flagg gave a historical address, reciting the story of the

massacre of the Moore and Reagan children, and Mrs. Reagan by

Indians, and the subsequent attempts of the settlers to avenge their

deaths. Mr. Flagg made a good address that was instructive, and he

showed ability as a public speaker. J. Nic Perrin then gave a brief

historical talk on the troubles with the Indians in the early days.

E. K. Preuitt, one of the oldest of the old settlers, then made a

talk, recalling the early days. The program was closed with singing

of “Nearer by God to Thee.”

The wagon road was choked with buggies and automobiles for a long

distance in the neighborhood of the monument, and there were many

who went on foot to attend the dedication.