Shurtleff College

Faculty | Shurtleff College Newspaper Articles

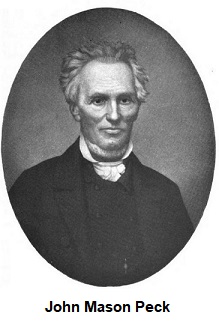

Asa Peck, John’s father, was afflicted with lameness, which placed a

large share of the farm work on John’s young shoulders. From the

time he was fourteen, his summers were devoted to the farm, and in

the winter months, he attended the local common schools. Peck later

stated that the school he attended must have been inferior to

others, as he was more stupid and sluggish than ordinary lads.

Others claimed that while John was uncultivated, he was no

simpleton. At the age of eighteen, on December 15, 1807, he attended

a church meeting, where the work of God’s converting grace brought

John to see himself as a guilty sinner, deserving God’s wrath. By

the end of the week, he converted to Christianity and accepted God’s

grace of salvation.

In 1807, John Peck began to teach school. He soon met Sally Paine, a

native of New York. Sally, whose legal name was Sarah, was an

extraordinary young woman. Her mother had died before she was twelve

years old, and she assumed the housework and charge of three younger

siblings for two years. When her father remarried, she went to

reside with her mother’s parents in Litchfield, Connecticut. There

she met Peck, and they married on May 8, 1809. They lived with his

father and mother about two years, and in 1811 they moved to

Windham, Greene County, New York, near her family’s home. Shortly

after the birth of their first son, they joined the Baptist Church.

Peck taught school, and served as pastor at the Baptist churches in

Catskill and Amenia, New York. He became interested in missionary

work after meeting Luther Rice, and went to Philadelphia to study

under William Staughton. There, Peck met James Ely Welch, a Baptist

minister, who became his missionary partner. The Peck and Welch

families traveled to St. Louis in December 1817. The population of

that “village” was about 3,000, of which one-third were slaves. He

later stated, “One half, at least, of the Anglo-American population

were infidels of a low and indecent grade, and utterly worthless for

any useful purposes of society.”

Peck and Welch organized the First Baptist Church of St. Louis, and

baptized two converts in the Mississippi River in February 1818.

They founded the first missionary society in the West – The United

Society for the Spread of the Gospel. With the missionary support

withdrawn, Peck refused to move back East, and continued his

ministry in St. Louis. Two years later, the Baptist Mission Society

employed Peck at $5 a week. He established Bible societies and

Sunday Schools, and ministered to the rural population. In 1818 he

traveled to Kaskaskia, then the seat of government of Illinois.

In February 1819, Peck felt it was time to establish a seminary for

the common and higher branches of education. It was a goal of his

before leaving the East – to train minds in habits of thinking and

logical reasoning, to educate in the gospel of truth, and to train

in Christian duties. It was deemed necessary to visit several

locations within fifty miles of St. Louis, in which to establish his

seminary. Rufus Easton of St. Louis, who projected the site of

Alton, made Peck promise that he would not locate his planned

seminary until he explored the village known as Upper Alton. On

February 22, 1819, Peck traveled to St. Charles, Missouri, and rode

to the “Missouri Point.” He took Smeltzer’s Ferry across the

Mississippi to Illinois, and traveled eastward to a small settlement

where Alton would later be established. He found four cabins, and

obtained directions on how to find the village of Upper Alton. The

previous year, Peck had met Doctor Erastus Brown, who had moved to

Upper Alton, and planned to make a visit to him there. Emerging from

the “forest” in Upper Alton, Peck found campfires and piles of brush

glowing with heat. There was a tavern or boarding house, where he

entered and found a table with rough, newly-sawed boards with an

old, filthy cloth covering it. The landlord, dirty in appearance,

supplied supper and a stable for his weary horse. Peck found a boy

and offered him a dime to take him to Dr. Brown’s newly-built log

cabin. There, Peck found Brown, his wife, and two or three children.

They welcomed him, and provided tea and food. He slept in a small

bedroom, and found comfort from the cold. In the morning, Dr. Brown

showed him around Upper Alton. There were 40-50 families living in

log cabins, shanties, covered wagons, and camps. At least 20

families were destitute of houses, but were gathering materials and

getting ready to build. There was a school of 25-30 boys and girls,

taught by a backwoods fellow. Peck wondered where enough scholars

could be found to fill a seminary at Upper Alton. He made his way

back to Smeltzer’s ferry, and it was 3 or 4 years until he visited

Upper Alton again.

Rev. Thomas Lippincott later wrote of John M. Peck that he was an

able man, with great zeal, power, and success. But he was not

received with cordiality by the brethren of the old churches. They

considered him an innovator, and after a few years, broke fellowship

with him. Lippincott seldom saw a man of physical and moral vigor

combined in one person equal to John M. Peck. He was always ready,

and sought all occasions to preach the gospel. Peck was just the

man, determined and able to build a seminary.

In the Autumn of 1820, Peck’s first son, a promising lad of about

ten years of age, came down with a fever and became so ill, that he

clung between life and death. His father and mother prayed for God

to spare him, but such was not the will of God. His son passed away,

and two days later Peck’s brother-in-law, Mr. S. Paine, also died.

Even in the midst of trials, Peck looked to God with reverence and

love and said, “Though he slay me, I will trust in Him.” Peck was

also afflicted with illness, but he was spared.

In 1822, Peck was appointed as the missionary of the Massachusetts

Baptist Missionary Society. His first commission in their service,

signed by the honored names of Thomas Baldwin, President, and Daniel

Sharp, Secretary, was dated March 12, 1822. Peck was to earn five

dollars a week, and was expected to raise money on the field of his

labors. His family remained for some time in the vicinity of St.

Charles, Missouri, but he was found in St. Louis, cheering on the

feeble Baptist churches there. At the end of April 1822, Peck moved

to St. Clair County, Illinois, which soon became his family

residence. He bought a half-section of unimproved land, and with a

little assistance from kind neighbors he built a home and began

cultivating the land to support his family. He called his farm “Rock

Spring.” A band of brethren, chiefly from Georgia, had settled

around the new home he had chosen, and they desired to form a

church. On May 26, 1822, the church was organized. Peck founded a

circuit to visit the various societies and churches in Missouri and

Illinois. He preached the word of God, baptizing and ministering

unto the people. On one trip, he visited Daniel Boone, then nearly

80 years of age, and later wrote a book of the frontiersman’s life.

On February 22, 1826, Peck left his home to journey back to the

East. By the end of March, he reached Washington D.C., and found

himself with old friends, Rice and Dr. Staughton, who welcomed him.

He visited the capitol, and heard speakers of that era. He preached

both in the city and in the college chapel, and in company with

members of Congress, he met President Adams, whom he had much

admiration for (Peck had just named his youngest son after the

President). He continued his journey, preaching and greeting old

friends, until he reached his mother’s home in Connecticut. He

visited old friends and neighbors, preached in the churches, and

visited colleges, to gain knowledge of the practices of New England

toward education. He found his mother living in poverty, paid her

debts and decided to bring her to his home in the West. He purchased

a two-horse carriage, and set forth for the difficult journey home.

Arriving safely at home, Peck began riding the circuit once again.

He visited Vandalia, then the seat of government, and conferred with

as many brethren, ministers, and public-spirited citizens as

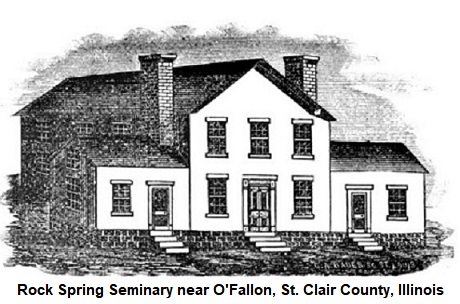

possible for the formation of a seminary. A meeting was held at Rock

Spring on January 01, 1827, and an organization of trustees formed.

They decided to locate the seminary at Rock Spring, on land given by

Mr. Peck for this purpose. By the end of May 1827, a seminary

building had been erected. Nearly everything connected with this

effort rested on his shoulders, and he was performing the work of

two or three men, besides his own duties preaching. However, Peck

was successful in the establishment of the seminary, which opened

with 25 students of both sexes. Rev. Joshua Bradley was the first

principal of the seminary. The number of students increased to 100

in a few weeks. In 1828, an agreement was reached with Rev. T. P.

Green and Mr. Peck, that a religious paper would be issued from Rock

Spring Seminary, with Peck as its editor. In about the middle of

December 1828, the “Pioneer” appeared. In 1829, the faculty at Rock

Spring Seminary was John Russell, Principal; Rev. John M. Peck,

Theology; and John Messenger, Mathematics, etc.

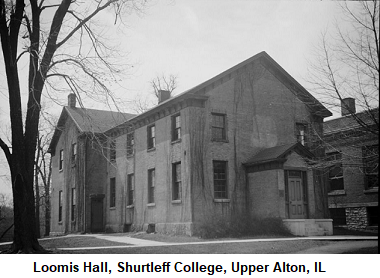

Although the seminary was thriving, it was operated on a small

scale. In 1832, Peck purchased a new site for a seminary in Upper

Alton, where he had once visited so long ago. He renamed his college

Alton Seminary, and a new organization was established under the

name of “The Board of Trustees of Alton Seminary.” Rev. Hubbel

Loomis, who had been teaching a seminary in Kaskaskia, was persuaded

by Peck to teach at the Alton Seminary. Loomis was elected

Principal. Loomis Hall, the first building of the Seminary in Upper

Alton, was erected in 1832 for a cost of $1500 or $2000. It housed

the administrative offices, classrooms, and the library. This

building still stands today, and houses the Alton Museum of History

and Art.

On

April 11, 1835, Peck left home at Rock Spring for the East once

again. He arrived at the capital on April 25. He preached among the

churches, and pleaded the cause of his Western institution. He

visited Dr. Shurtleff in Boston, and appealed for aid. Shurtleff

proposed giving $10,000 (which would be $341,863.64 in 2023,

according to the inflation calculator) for building purposes, if the

college would be renamed Shurtleff College, and a professorship of

rhetoric and elocution was formed. On October 9, Peck left New

England, and on November 18, he reached his home at Rock Spring and

found his family well. In January 1836, the charter of the seminary

was amended by changing the name of the Board to The Trustees of

Shurtleff College of Alton, Illinois.

On

April 11, 1835, Peck left home at Rock Spring for the East once

again. He arrived at the capital on April 25. He preached among the

churches, and pleaded the cause of his Western institution. He

visited Dr. Shurtleff in Boston, and appealed for aid. Shurtleff

proposed giving $10,000 (which would be $341,863.64 in 2023,

according to the inflation calculator) for building purposes, if the

college would be renamed Shurtleff College, and a professorship of

rhetoric and elocution was formed. On October 9, Peck left New

England, and on November 18, he reached his home at Rock Spring and

found his family well. In January 1836, the charter of the seminary

was amended by changing the name of the Board to The Trustees of

Shurtleff College of Alton, Illinois.

Between 1836 – 1841, the average number of students in attendance

was eighty-eight, with four instructors. The price for lodging at

the college in 1842 was from $1.50 to $1.75 per week. Food was an

additional $1.00 per week. The faculty in 1839 was Rev. Washington

Leverett, A. M., President and Professor of Moral Philosophy,

Mathematics and Natural Philosophy, Oratory, Rhetoric and Belles

Lettres, and Ancient Languages; Rev. Warren Leverett, A. M.,

Principal of the Preparatory Department; and Rev. Zenas B. Newman,

Assistant English and Classical Tutor.

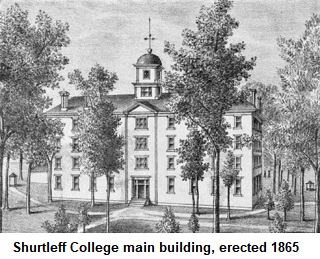

On April 24, 1839, the trustees decided to erect a large building

that would serve the growing needs of the college for many years.

With the help of the experience of Dr. Peck, the four-story brick

building, containing 64 rooms, was erected. Mr. Zephaniah Lowe was

the contractor. In later years, hot water heating was added, which

replaced individual fireplaces or stoves. Bathrooms were added, and

the tall chimneys were removed. The old 8x10 glass in the windows

were replaced. An old bell, which used to swing over a popular

Mississippi River steamer, was hung on the building.

On June 13 1852, Peck mentioned in his diary of having his five

sons, with two of their wives and two grandchildren, at home and

surrounding the supper table together. They were five strong, hardy

men, from 21 – 38 years of age. On November 18, 1852, the original

Rock Spring Seminary building – where it all began – was destroyed

by fire. His son was working in the lower story and had a fire in

the fireplace. Leaving for a few moments, he returned and found the

wind had scattered fire among the combustibles around his workbench,

and the flames soon reached the ceiling above. John Peck’s

collection of files of papers, periodicals, and pamphlets, amounting

to several thousand volumes, were all destroyed. In January 1853, he

gathered his scattered and charred books - 1,500 volumes - into the

largest room in his house, which then became his library and study.

Peck resigned his duties on March 19, 1854, after receiving news

from his doctor that he had lung disease. He became frail as some

men at the age of 86. At the end of the year, he received news of

the death of his son, Harvey Jenks Peck, who died in Iowa on

December 17, 1854, a little over 41 years of age. For the remainder

of his life, Peck wrote in his diary and visited with friends,

including Cyrus Edwards of Upper Alton. On Sunday, March 14, 1858,

he passed away in his family home at Rock Spring, and was buried in

the Rock Springs Cemetery in O’Fallon. Twenty-nine days later, at

the special request of many friends and colleagues, his body was

disinterred and reburied in the Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis,

to rest with other pioneer Baptist ministers.

In about 1872, Shurtleff College was opened to young women. In later

years, the chapel, gymnasium, girl's dormitory, Martha Wood Cottage,

boarding hall, and the science annex were erected as demands were

met.

In June 1873, the Board of Trustees of Shurtleff College purchased

the private residence of Mr. Hiram N. Kendall for $20,000, for the

purpose of the women’s department.

In 1877, Doctor Benjamin Franklin Edwards passed away. His

connection to Shurtleff College dated back to 1827, when Rock Spring

Seminary was founded. Edwards served on the board of trustees for

the seminary from its beginning.

Carnegie Library

In 1907, wealthy businessman Andrew Carnegie gave $15,000 to

Shurtleff College for the purpose of building a library. The college

had to raise $15,000, in addition to Carnegie’s donation. Carnegie

had first objected to giving money to Shurtleff, as he heard that

too many students were educated for free, and he protested against

this, expressing his belief that students should pay for their

education. At last he was convinced to give, and the Carnegie

Library was erected.

Fire Destroys Original Main Building

The original main building, erected in 1865, was destroyed by fire

in 1938. It was replaced with a large, two-story, stone building in

1940, which still stands today.

Shurtleff College continued to grow and prosper throughout the years, ending its existence on June 30, 1957. The college reached its peak of enrollment in 1950, with 700 students. After its closure, the college because part of the Southern Illinois University system.

FACULTY OF ROCK SPRING SEMINARY - SHURTLEFF

COLLEGE

1829 (Rock Spring Seminary)

Principal – John Russell

Rev. John Mason Peck – Theology

John Messenger – Mathematics, etc.

1839 – Shurtleff College

Rev. Washington Leverett, A. M. – Mathematics, Natural Philosophy,

Oratory, Rhetoric, Fine Literature

Rev. Warren Leverett, A. M. – Preparatory Department

Rev. Zenas B. Newman – Assistant English and Classical Tutor

1849

Rev. Washington Leverett, A. M. – Mathematics and Natural Philosophy

Rev. Warren Leverett, A. M., Latin and Greek Languages

Erastus Adkins, A. M. – Oratory, Rhetoric, Fine Literature,

Chemistry, Mineralogy

Rev. Justus Bulkley, A. B. – Tutor and Principal of Preparatory

Dept.

William Cunningham, A. B. – Tutor and Principal of Preparatory Dept.

1869

Rev. Daniel Read, LL. D., President – Mental and Moral Science

Oscar Howes, A. M. – Latin and Greek Language, Literature

Charles Fairman, A. M. – Mathematics, Natural Philosophy

Orlando L. Castle, A. M. – Oratory, Rhetoric, Fine Literature

Ebenezer Marsh Jr., A. M. Ph.D – Chemistry, Geology, Mineralogy

Edward A. Haight, A. B. – Principal of Preparatory Department

Rev. Edward C. Mitchell, A. M. – biblical Literature and

Interpretation

Rev. Robert E. Pattison, D. D. – Systematic Theology, History of

Doctrine

Rev. Justus Bulkley, D. D. – Church History and Polity

1889

Rev. A. A. Kendrick, D. D., President – Systematic Theology

Orlando L. Castle, LL. D. – Oratory, Rhetoric, Fine Literature

Rev. Justus Bulkley, D. D. – Church History and Polity, Biblical

Literature and Interpretation

Charles Fairman, LL. D. – Mathematics and Natural Philosophy,

chemistry, Geology, Mineralogy

David G. Ray, A. M. – Latin and Greek Language, Literature

L. F. Schussler, M. D. – Physiology

1899

Austen Kennedy De Blois, PhD., LL. D., President – Psychology,

Ethics

Rev. Justus Bulkley, D. D., LL. D. – History

George Ernest Chipman, A. M., LL. B. – Political and Social Science

Samuel Ellis Swartz, PhD. – Natural Science

David George Ray, A. M. – Latin and Greek

Charles Hoben Day, A. M. – Modern Languages

Victor Leroy Duke, A. B. – Mathematics

David H. Jackson, B. L. – Physiology, Physical Culture

James Primrose Whyte, A. B. – English Literature, Oratory

Edward C. Lemen, A. M., M. D. – Medical Examiner