Early History of Collinsville

Collinsville Newspaper Articles

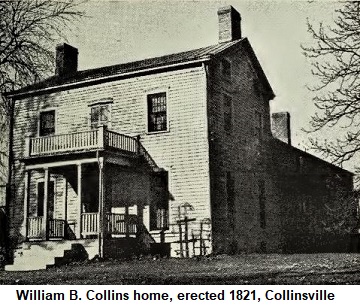

The original town plat of Collinsville was laid out by the

representatives of William B. Collins, deceased; Joseph L. Darrow;

and Horace Look. The plat was recorded May 12, 1837.

The first settler on the present site of Collinsville was John A.

Cook, who entered land, erected a log cabin, and made some

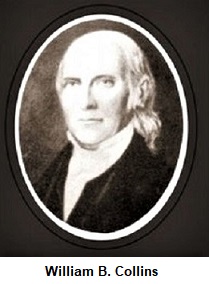

improvements in 1816. In 1817, three brothers, Augustus, Anson, and

Michael Collins, from Litchfield,

Connecticut,

purchased the property of Mr. Cook, and immediately commenced

improvements. They erected a distillery made of logs, with two

stills – one of 30 gallons and the other of 60 gallons capacity – a

frame storehouse, a large double-decked ox-grist and saw mill,

cooper shop, blacksmith, wagon and carpenter shops, tan yard, and

several dwellings. The Collins brothers gave the name of Unionville

to their new town. The parents of the Collins brothers, sisters, and

more brothers came to the new town to live, including brothers

William B. and Frederick Collins. One of their first objective was

the erection of a commodious place of worship, which also served as

a schoolhouse. Only one of the brothers, Augustus, was married,

however soon William B. Collins married a daughter of Mr. Hertzogg

of St. Louis, who was then running a mill in the American Bottom.

Michael Collins married a daughter of Captain Blakeman, and

Frederick Collins married a daughter of Captain Allen – both of the

Marine settlement.

Connecticut,

purchased the property of Mr. Cook, and immediately commenced

improvements. They erected a distillery made of logs, with two

stills – one of 30 gallons and the other of 60 gallons capacity – a

frame storehouse, a large double-decked ox-grist and saw mill,

cooper shop, blacksmith, wagon and carpenter shops, tan yard, and

several dwellings. The Collins brothers gave the name of Unionville

to their new town. The parents of the Collins brothers, sisters, and

more brothers came to the new town to live, including brothers

William B. and Frederick Collins. One of their first objective was

the erection of a commodious place of worship, which also served as

a schoolhouse. Only one of the brothers, Augustus, was married,

however soon William B. Collins married a daughter of Mr. Hertzogg

of St. Louis, who was then running a mill in the American Bottom.

Michael Collins married a daughter of Captain Blakeman, and

Frederick Collins married a daughter of Captain Allen – both of the

Marine settlement.

The brothers worked well together and their new town prospered and

grew. The distillery of the Collins brothers was considered first

rate, and their inclined wheel ox-mill flour commanded an extra

price in eastern markets. A post office was opened, but it was

discovered that there was already a town by the name of Unionville,

and the Postmaster suggested changing the name of the town to

Collinsville, which was accepted by the brothers.

The brothers soon were convinced that the production of liquors was

sinful and unchristian. They ceased operation and totally demolished

the building and broke up the generators. They took the huge tanks

in the distillery to their homes to use as cisterns, and they sold

the wash tubs to farmers for granaries. After this time period, the

brothers separated. Augustus Collins died, and several brothers went

to the Illinois River and established mills at the town of Naples.

William B. Collins remained alone at Collinsville, carrying on the

business, minus the distillery, until his death in 1849.

In 1820, Mr. Wilcox from New York located in Collinsville and began

the tanning business for ten years, then selling out to Hiram L.

Ripley. Another New Yorker, Horace Look, came west in 1818, and

settled in Collinsville in 1821. He was a harness maker, and formed

a partnership in that business with Mr. Wilcox. Mr. Look was an

early Justice of the Peace, and was postmaster in Collinsville for

nearly thirty years.

Among other early and enterprising residents were Benjamin Johnson,

Aaron Ford, Isaac and Ebenezer Lockwood, James Haffey, Jesse Glover,

Aaron Small, Dr. Gunn (the first physician), Dr. Samuel Hall, Dr.

Gurnsey, Dr. Strong, Dr. Henry Wing, Dr. William S. Edgar, Dr. J. L.

Darrow, and Captain William N. Wickliffe. Richard Withers, a

blacksmith, had at one time quite an extensive plow factory. Peter

and Paul Wonderly owned a distillery and operated the first coal

mine.

Daniel Berkey, a native of Pennsylvania, came west and settled in

Collinsville in 1830. Joshua S. Peers came from New York with his

father, and became one of the prominent citizens of Collinsville.

The first house of worship in Collinsville was a frame building

erected in 1818. It was a Union Church, used by all denominations,

and also for school purposes. Rev. Salmon Giddings organized a

Presbyterian society in 1817. Revs. James and Joseph Lemen, Thomas

Lippincott, and Isaac McMahan were among the early preachers. By

1882, there were five churches in Collinsville – Presbyterian,

Methodist, Episcopal, Catholic, and Lutheran.

The earliest school in Collinsville was taught in the Union Church.

Philander Braley, who had been teaching there for some time, erected

a schoolhouse with his own money and established a private school.

His school became well known, and was patronized by citizens from

St. Louis. He later moved to Carlinville. The Braley schoolhouse was

a two-story frame building, which was the property of Dr. H. L.

Strong. It was located on the southwest side of Center Street, south

of Main. Mr. Braley was followed by Rev. Charles E. Blood, pastor of

the Presbyterian Church. Blood erected a two-story frame building

and established an academy. He introduced higher classes, and

prepared students for college. This building was purposed by the

directors, and in it the first public school was taught until 1867,

when it was moved, and became part of the Wilson Bell Factory. On

the property a new three-story brick schoolhouse was erected. In

1872 this schoolhouse was destroyed by fire. A new schoolhouse was

constructed on the property in 1873 – a three-story brick structure

with dressed limestone and yellow fire-brick trimmings, with a

cupola on the top. It had twelve rooms, four on each floor.

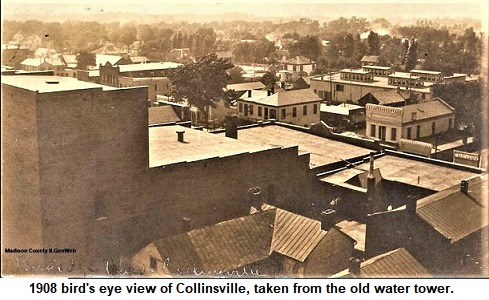

Collinsville was incorporated under the general law as a village in

1850. The following were elected: D. D. Collins, President of

Trustees; A. Tufts, clerk; J. J. Fisher, H. L. Ripley and Horace

Look, trustees. On November 11, 1872, an election was held for city

officers: Mayor, John Becker; Aldermen, A. W. Brown, James Combs, J.

J. Fisher, C. Kalbfleisch, A. M. Powell, and J. M. Verneuil; City

Clerk, J. G. Gerding; City Attorney, Edward Wilburn. John G. Blake

was appointed city Marshal and City Superintendent of Streets.

The Vandalia Railroad was constructed through Collinsville in 1868,

and the town soon began new growth and prosperity. Coal interests

were soon developed and became an important business. Coal was

underlying the whole surface of this region of the country, with the

vein at Collinsville averaging from seven and a half to eight feet

in thickness. The Collinsville Coal and Mining Company was the owner

of the first coal shaft in Collinsville. George Savitz was

President, with J. H. Wickliffe as co-owner. They operated two

shafts, the second of which was sunk in 1873. The Lumaghi Mine was

opened in 1869 by Octavius Lumaghi. The Cantine Coal and Mining

Company opened their mine in 1873, and was owned by Morrison and

Ambrosius. The Abbey Coal and Mining Company, the most extensive

mining company at that time, was sunk by Reid and Strain in 1875.

The Collinsville Flour Mill, was founded in about 1850 by James

Matthews. It later became the property of Baker & Company, and had a

grinding capacity of 150 barrels per day. They produced Argentine

and Sonora flour. Another flour mill was the Cantine Mill, owned by

F. Lange and leased by J. Higley. It was four stories high, frame,

with a capacity of 150 barrels per day.

The Collinsville Zinc Works was founded in 1875 by Dr. Octavius

Lumaghi, for the smelting of zinc ore at his coal mine. In 1881, he

leased the works to Parks & Brothers, who after operating for three

months, their company failed. In January 1882 the works was leased

by Reichenbach & Company. In January 1897, the zinc works, then

owned by the Meister Brothers, was destroyed by fire.

The Stock Bell Factory was established by I. C. Moore. Mr. Wilson

purchased by property in 1876, and made many improvements in the

machinery and manufacturing process. The machinery was run by steam

power, and from 150 to 200 dozen bells were manufactured per day,

employing ten to twenty men in 1882. Mr. Wilson invented and

patented a process for coating bells with brass. His bells were sold

to dealers in all cities in the United States.

The Blum & Schoettle’s Stock Bell Factory was established in July

1879. It was a one-story building, and the company had a capacity of

manufacturing 100 dozen bells per day, employing from twelve to

fifteen men.

In the northeastern limits of Collinsville was located the brickyard

owned by Fred Hoga. It was established in 1879, and contained two

kilns where about 700,000 brick were annually burned.

In April 1879, a tornado tore through the town of Collinsville,

killing a little girl named Annie Reynolds, and severely injuring a

six-year-old boy, taken unconscious from his home with a broken leg.

Many others were injured. About thirty homes were totally destroyed,

as well as many businesses damaged. The blacksmith shop of Mr.

Wnedler was torn to shreds, and the wagon shop of John Gronour was

also destroyed. The W. W. Nilson carpenter shop, a saloon and

boarding house, and millinery store were either destroyed or

severely damaged. In the cemetery just outside of town, nearly every

tombstone was leveled to the ground.

In 1891, the Illinois House, a hotel five miles west of Collinsville

on the St. Louis plank road, was destroyed by fire. The building was

within a few hundred feet of Monks Mound. For over half a century it

had offered hospitable shelter to the traveler, and was a popular

stopping place for the stagecoach drivers and teamsters going to and

returning from St. Louis. The building had a dance hall connected,

in which were held many joyous social entertainments. Captain John

Schmidt was the proprietor when it was burned down.

***********************

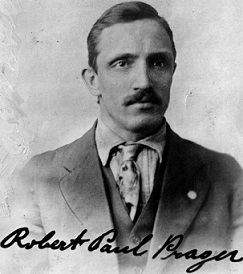

THE LYNCHING OF ROBERT PAUL PRAGER - April 5, 1918

Suspected of Being German Spy

Source: The Troy Call, Troy, Illinois, April 5, 1918

Robert

Paul Prager, an alien enemy, 39 years old, and suspected of being a

German spy, was hanged by a mob at Mahler Heights, west ofRobert

Paul Prager Collinsville, about 1 o'clock this morning. Prager had

been under surveillance for some time because of alleged disloyal

remarks. He was in Maryville yesterday, where he posted a

proclamation declaring his loyalty, and as a result he was run out

of town. He was followed to Collinsville by a number of men, and a

mob soon assembled at the Suburban "Y." It proceeded to the Bruno

bakery where Prager was found and taken out and marched down the

street in his bare feet with an American flag wrapped around his

body. Police rescued Prager from the mob and took him to the city

jail in the city hall. The crowd then went to the jail and demanded

that Prager be turned over to them. In the meantime, Mayor Siegel

had been summoned and pleaded with the men not to resort to

violence. It was then Prager was taken out of his cell and concealed

among the rubbish of the city hall. The mob dispersed after the talk

by Mayor Siegel, but returned after several hours and made a search

for Prager, who was taken out and hurried down the street. The

police say they were unable to handle the situation.

Robert

Paul Prager, an alien enemy, 39 years old, and suspected of being a

German spy, was hanged by a mob at Mahler Heights, west ofRobert

Paul Prager Collinsville, about 1 o'clock this morning. Prager had

been under surveillance for some time because of alleged disloyal

remarks. He was in Maryville yesterday, where he posted a

proclamation declaring his loyalty, and as a result he was run out

of town. He was followed to Collinsville by a number of men, and a

mob soon assembled at the Suburban "Y." It proceeded to the Bruno

bakery where Prager was found and taken out and marched down the

street in his bare feet with an American flag wrapped around his

body. Police rescued Prager from the mob and took him to the city

jail in the city hall. The crowd then went to the jail and demanded

that Prager be turned over to them. In the meantime, Mayor Siegel

had been summoned and pleaded with the men not to resort to

violence. It was then Prager was taken out of his cell and concealed

among the rubbish of the city hall. The mob dispersed after the talk

by Mayor Siegel, but returned after several hours and made a search

for Prager, who was taken out and hurried down the street. The

police say they were unable to handle the situation.

Prager was marched out to Mahler Heights, west of Collinsville, and

forced to kneel. Arms crossed, he prayed in German for a few

minutes. The men placed a rope around his neck and Prager was swung

to a tree for several seconds. He was then let down and asked if he

had anything to say and requested that he be permitted to write a

farewell to his parents in Germany. His brief letter follows:

"Carl Henry Prager, Dresden, Germany. Dear Parents:

I must, this the fourth day of April 1918, die. Please pray for me,

my dear parents. This is my last letter and testament. Your dear son

and brother, Robert Paul Prager."

After being permitted to write the note, Prager was again drawn up

by the rope and left hanging, and the mob dispersed quietly. Prager

had worked as a baker at the Bruno bakery for several years, but of

late had been trying to secure employment at the coal mine at

Maryville. He was denied union membership there because of his

disloyal remarks against the United States. He was registered in St.

Louis as an alien enemy. The authorities are indignant over the

affair. Attorney General Brundage and State's Attorney Streuber have

denounced the lynching as a disgrace and declare that the members of

the mob must suffer for the act which was as unlawful as it was

heinous and horrible. President Wilson and his cabinet have also

denounced the affair. Attorney General Brundage is expected in

Collinsville today, and the inquest into the death of Prager is

expected to be held Monday.

********************

EDITOR'S NOTES:

During the height of World War I, Prager, a coal miner, made

speeches to his fellow coal miners on Socialism, and made derogatory

remarks regarding American President Wilson. Prager had been under

surveillance for some time, with some authorities fearing he was a

German spy. The fear of German spies was prevalent throughout

America, and bridges and vital businesses were guarded by the

military to prevent sabotage. Many Germans pledged allegiance to

America publicly, and some even changed their names to become more

“Americanized.” The day before his lynching, Prager put up posters

at the Maryville mine, proclaiming his loyalty to the American

government.

The miners became incensed at Prager’s action. When they threatened

to do him bodily harm, he escaped to Collinsville where he lived. He

was followed, captured, and lynched. In Prager’s pocket was found a

long “proclamation” in which he stated his loyalty to the United

States and to union labor. The location of the hanging was along St.

Louis Road in Collinsville, near the St. John Cemetery.

The news of the lynching of Robert Prager spread throughout the

country. The Swiss embassy in Washington D.C., which was attending

to German interests in America, offered to pay the funeral expenses,

however the state of Illinois paid the funeral expense, and sent the

Swiss embassy a bill. The funeral was held in St. Louis at the

Harmonie Lodge of the I. O. O. F., of which Prager was a member, and

he was buried in the St. Matthews Cemetery in St. Louis.

Men Accused of Lynching Robert P. PragerJoseph Riegel, Wesley

Beaver, Richard Dukes Jr., William Brockmeier and Enid Elmore, all

of Collinsville, were arrested at the request of the coroner's jury

investigating the death of Robert P. Prager. Following the inquest,

the men were taken to Edwardsville to await the action of the

Madison County Grand Jury. Riegel, a proprietor of a shoe repair

shop in Collinsville, previously had admitted to being the leader of

the mob. Two of the other men were miners, and one a porter in a

saloon.

The trial was held in May 1918. The eleven defendants arrived in the

courtroom wearing American flags. The jury included: Keith Ebey,

clerk, Edwardsville; T. Benett, railroad car accountant,

Edwardsville; George Neary Sr., janitor, Edwardsville; Walter

Solterman, teamster, Worden; W. C. Dippold, flour miller,

Edwardsville; Marion Baumgartner, tailor, Edwardsville; D. W.

Fiegenbaum, manufacturer, Edwardsville; John Groshans, farmer,

Edwardsville; A. H. Challacombe, plumber, Alton; Frank Oben, horse

and mule buyer, Alton; F. W. Horn, tailor, Alton; Frank Weeks,

clerk, Edwardsville.

State's Attorney Streuber made a brief opening statement: "We do not

represent Prager nor any pro-German nor any pro-German sentiment,"

he declared. "We have made an effort to keep possible pro-Germans

off the jury and I believe we have one that is 100 percent loyal.

Our only interest is to see that the law is upheld. If Prager was

either a pro-German or a spy, there was a remedy at law, and we aim

to show that a mob took the law upon itself, which is in itself a

violation."

James M. Bandy, chief counsel for the defense, then spoke briefly.

He declared there was evidence to show Prager's disloyalty and that

"after all the evidence is in, the jury will not return a verdict of

guilty."

More than 100 witnesses were summoned to appear at the trial. The

men were declared not guilty by the jury and were set free. The

announcement of the verdict was greeted with loud cheers, and when

the men filed out of the courthouse, they joined in a parade headed

by the Great Lakes “Jackie” Band. The acquittal was no great

surprise to those who heard the evidence in the case. The state

failed to prove the actual participation of any of the accused men.

As a result, one county paper asserted that Prager must have hung

himself.

Following announcement of the verdict, State's Attorney Streuber

dismissed the charges against five others who were implicated in the

Prager case. They were George Davis, Martin Futchek, Fred Frost,

Harry Stevens, and John Tobnick. The latter four were police

officers and were charged with malfeasance in office.

In September 1919, it was announced that Robert Paul Prager’s body

was to be exhumed and moved “from one of the humblest graves” in the

cemetery to one of the “prettiest spots in the burial grounds.” The

Harmonic Lodge No. 353, I. O. O. F., was to pay for the exhumation

and re-burial. They also erected a monument for Prager.